|

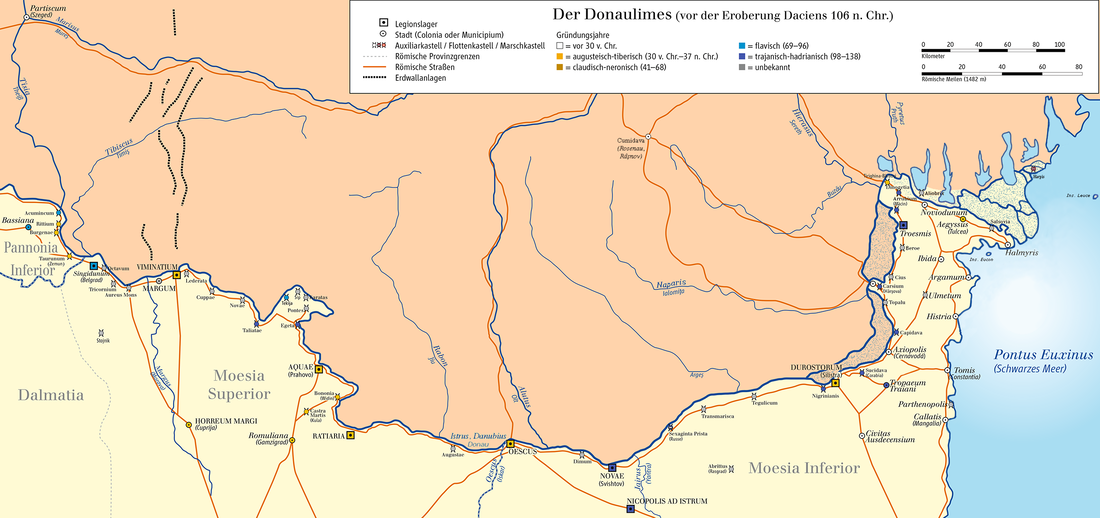

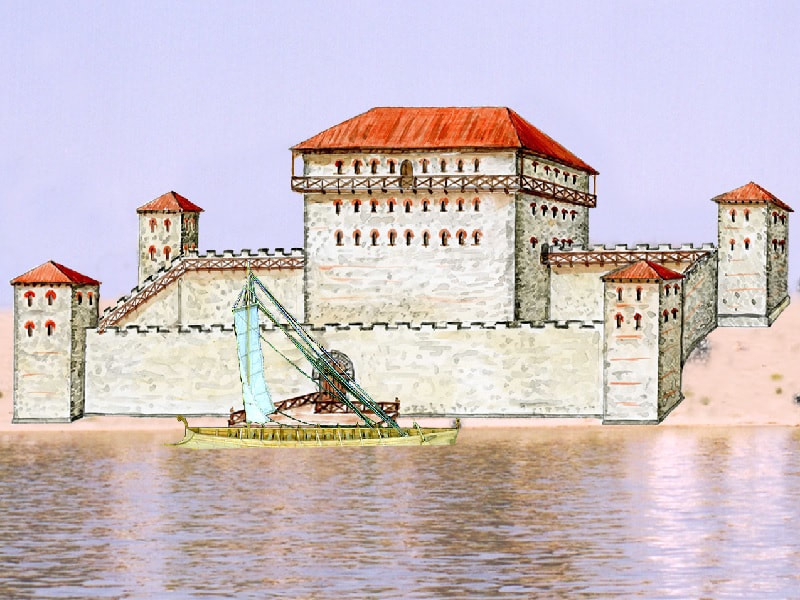

The River Danube, named after the Celtic or Scythian Mother Goddess Danu, goes by several other names. The Greeks knew it as the Istros (meaning 'strong, swift'), the Phrygians as the Matoas (bringer of luck), the Mongolians as the Thona. After the Volga in Russia, the Danube is the second longest river in Europe, running through ten modern countries. 2,000 years ago, it was established as the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. As such, it effectively shaped and defined the empire, and remained as the edge of the realm (give or take a few periods of further conquest and enemy invasion) all the way through late antiquity and on into the 'Byzantine' period. As such, the southern banks were studded with forts, watchtowers and river ports. The late Roman Army established a particular class of soldiery to guard this frontier: the limitanei ripenses, meaning 'the soldiers on the riverbank'. Skilled scouts, skirmishers and boatswains, these troops were the first line of defence against threats from the wild north, also known as 'barbaricum'. Their job was to watch for attacks and repel them if they could. If the attack proved to strong they would instead do their best to contain the enemy while raising the alarm and summoning the heavy troopers and cavalry of the closest field army (a central reserve) to the scene. The Danube was not only a naturally defensible barrier, but also a highway for trade ships, carrying amber, wine, furs, livestock, spices and silks and much much more to and fro between Western Europe and the Black Sea. It was, and remains, a provider too, replete with carp, sturgeon, salmon and trout. A few species of euryhaline fish, such as European seabass, mullet, and eel, inhabit the Danube Delta and the lower portion of the river. At various times, a number of bridges spanned the river - some of stone, some of wood, and sometimes temporary pontoon bridges made of strapped together boats. One of the most famous bridges was that built by Emperor Trajan (see image, below). Built in the 2nd century AD to allow his troops to cross onto the northern banks and make war with the Dacians, it remained in place for over 160 years, before falling into disrepair. Piers from the bridge still remain in situ today. Sometimes it suited the Romans to have easy access across the river and back... sometimes it definitely did not. For example, come the late 4th century AD, the Huns descended from the Eurasian steppe, they drove before them countless terrified Germanic and Scythian tribes. Had it not been for the Danube - by then (perhaps deliberately) bridgeless - the tribes could have spilled unchecked into the empire, no doubt quickly followed by their Hunnic pursuers. Instead, the broad waters of the Danube served as an impassable barrier, allowing the Romans to negotiate with and prudently admit tribes on terms that would be beneficial for both parties. That was the theory, at least... because when the Thervingi Goths were permitted to cross into Roman Thracia, greedy imperial officials abused and profiteered from the refugees, triggering the ruinous Gothic War - a 'domino' event that started with Emperor Valens being slain in battle and would one day lead to the sack of Rome itself.

0 Comments

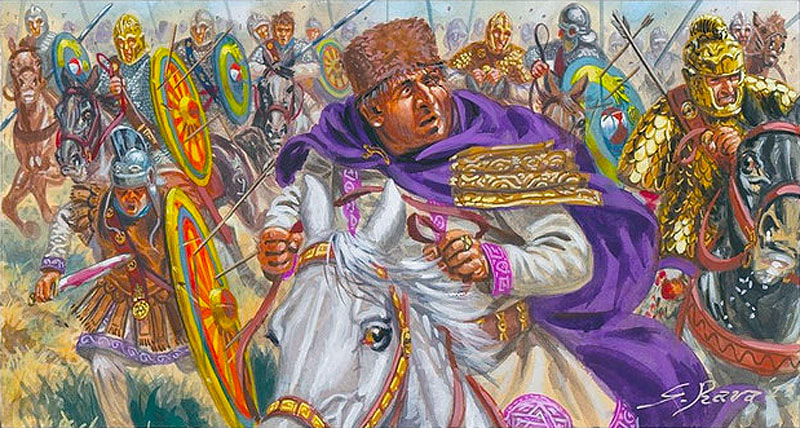

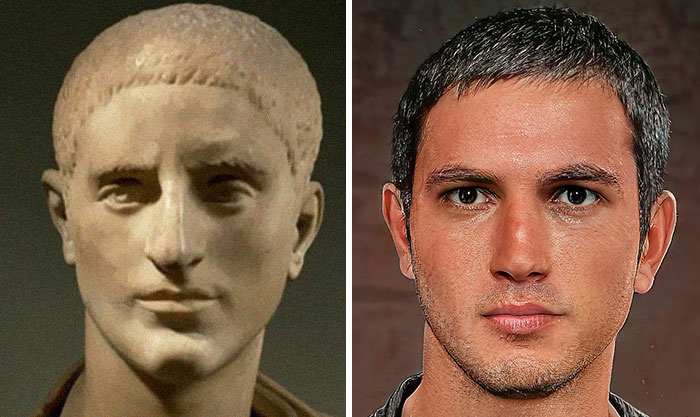

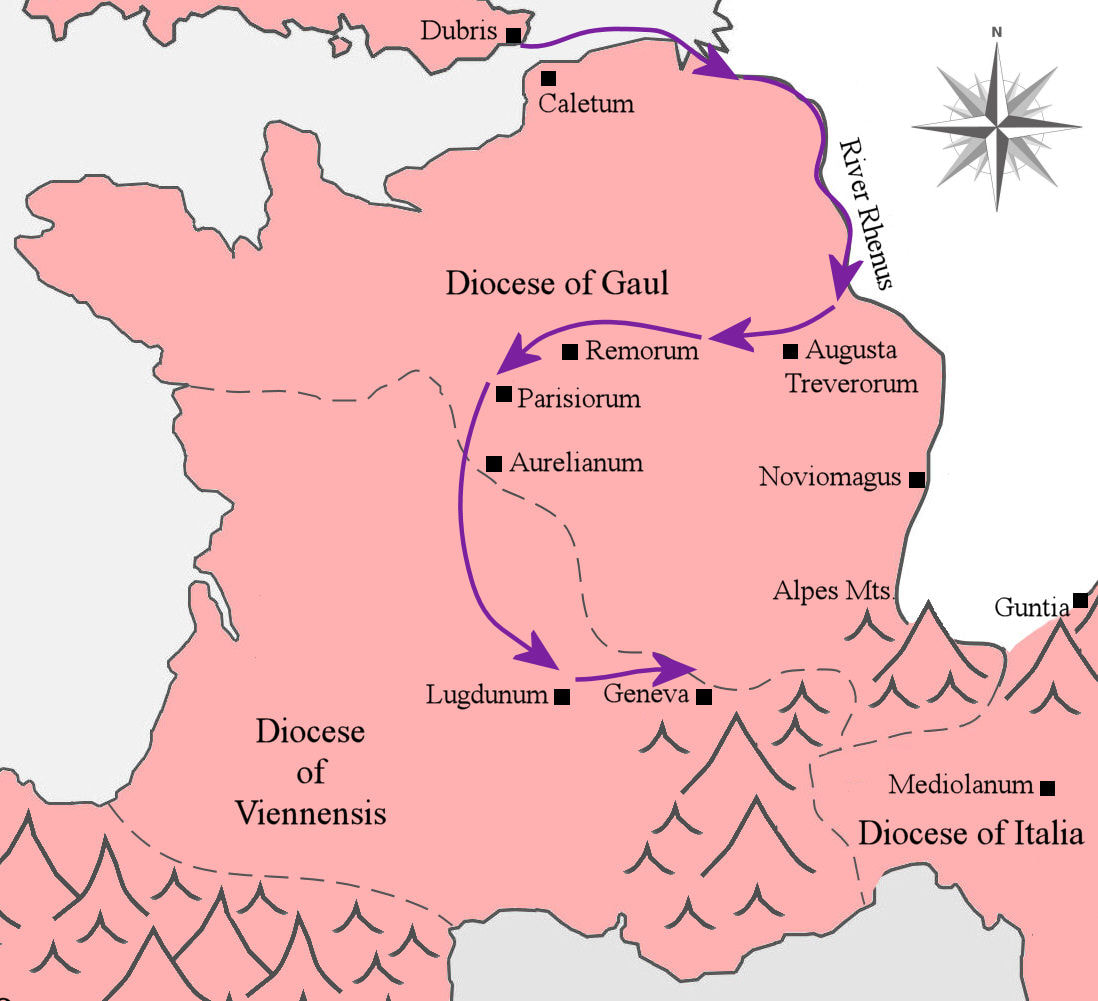

This is Magnus Maximus (meaning "Maximus the Great"). He earned the epithet "Magnus" thanks to a distinguished military career in the Roman legions. Born in AD 335 in Spain, he first rose to prominence in AD 368, when he served as a junior officer in the Heruli - an elite auxilia palatina, or palace regiment of the Western Empire. In this role, he helped the Roman general, Theodosius the Elder, to quell the Great Conspiracy in Britannia - a dangerous movement that saw the garrison of Hadrian's Wall rebel against the empire and ally with several barbarian tribes in an attempt to wrest control of the island from the empire. After playing his part in this famous imperial victory, he would go on to fight and win against the Alemanni on the Danube River and the Moors in Africa. It seems that he might even have played a part in supporting the ascension of Theodosius the Younger (his general's son) to the throne of the Eastern Roman Empire in AD 379. Eventually, he would return to Britannia after being promoted to the position of Comes Britanniarum - master of the island. His next triumph was against the Picts in AD 381. It seemed that his stock was destined to fly as high as the eagles, and that he would be remembered for all time as a Roman hero. Fast-forward seven years, to the 28th August 388 AD. On that day, he was seized by his fellow Romans and dragged out from his new headquarters at the city of Aquileia in northern Italy and, to a chorus of jeering, was beheaded like a common criminal. What on earth happened to bring about this spectacular fall from grace? Envy"Maximus was the countryman, the fellow-soldier, and the rival of Theodosius, whose elevation he had not seen without some emotions of envy and resentment. His provincial rank might justly be considered as a state of exile and obscurity." Maximus was a man of frustrated ambition. He had watched Theodosius the Younger climb all the way to the Eastern throne, and yet he was stuck as the count of the relative backwater of Britannia. Come AD 383, an opportunity would arise to improve his station. On the continent, the reputation of the Western Roman Emperor, Gratian, had begun to slide from favour. His propensity for hunting to the neglect of the empire's problems raised discontent amongst the people. As Gibbon describes: "Large parks were enclosed for the Imperial pleasures, and plentifully stocked with every species of wild beasts, and Gratian neglected the duties and even the dignity of his rank to consume whole days in the vain display of his dexterity and boldness in the chase. Gratian also seems to have let his duty of governance drift into the hands of his bishops and advisors, at a time when the West needed a strong guiding hand. The army too, took umbrage at his favouring of a body of Alani (Iranian steppe warriors) as his household guard. And when he began parading around in Alani warrior garb, they had seen enough. The first standard of revolt was raised in Britannia, where the troops proclaimed their count, Maximus, as the true Western Emperor. Yet Maximus initially refused the acclaim. A modest reaction... or a strategic one designed to absolve him of blame for what might happen next? Regardless of Maximus' apparent modesty, the cries of revolt had been heard across the English channel. Gratian began to mobilise to meet the threat. Now, with the spectre of the hated Gratian readying to attack his islanders, Maximus accepted his troops' acclaim and stepped to the head of the revolt, announcing that they should strike first, before Gratian could fall upon them. The army of Britannia was already potent, with many seasoned veterans in its ranks. Adding to this, the young men of the island flocked to Maximus' banner, eager to carry him to victory. In AD 383, when he set sail for the continent on board an invasion fleet, it would long be remembered as the first permanent and most drastic removal of the large body of troops stationed in Britain. The elite Dalmaturum (Dalmatian) and Sarmaturum (Sarmatian) cavalry schools in particular were irreplacable. "After this, Britain is left deprived of all her soldiery and armed bands, of her cruel governors, and of the flower of her youth, who went with Maximus, but never again returned" Maximus avoided the obvious landing point of Caletum (Calais) and instead sailed up the Rhine, deep into Gratian's Gaulish heartland, before striking overland. On the way many of Gratian's soldiers - instead of resisting the invasion, joined it. Gratian, in residence in Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris), tried to resist Maximus, but his support crumbled. He fled for Lugdunum (Lyon) where his wife was in residence, with only five hundred cavalry for protection. But Maximus had despatched his chief general, Andragathius, to speed ahead of his fleeing rival. Arriving at Lugdunum first, Andragathius reportedly hid in the veiled litter of Gratian's wife and had soldiers carry it out to greet the fleeing emperor. He then sprang out, armed, upon Gratian. A grim chase ensued, resulting in Gratian's ignominious capture and execution at a bridge in the countryside. The Western Empire had been 'liberated' and Maximus was the new emperor. But in the eyes of the Eastern Emperor, Theodosius, his revolt had been illegal, taking place without even seeking permission from him. An insatiable thirst for powerTheodosius initially accepted Maximus as Gratian’s successor and recognised him as Augustus of the West. However, it was only ever a pragmatic and necessary tolerance, given the difficult times in the East (a period riddled with Gothic and Persian troubles). A permanent and growing tension reigned, with Theodosius weathering accusations of weakness for his inaction against the usurper. Yet the alternative – heading straight to war against the new, well-supported Western supremo – could be catastrophic. Instead, he opted to bind Maximus to an oath that he would satisfy himself with the governorship of Gaul, Hispania and Britannia, leaving Italia and Africa to the young Valentinian II - Gratian's younger brother. Maximus took this oath, and quickly arranged to be baptised, a move perhaps taken to increase his standing with the Orthodox majority in Rome’s growing echelons of Christian power (at the pinnacle of which was Emperor Theodosius himself). The usurper seemed to be doing all the right things in order to be accepted. Yet at the same time, he made the rather unique and macabre decision to keep Gratian’s body unburied. And he carried out the notorious and entirely unjustified execution of Bishop Priscillian - citing withcraft and heresy. These two moves suggest a ruthless and dark side to his character. And soon after swearing his oath to Theodosius, he began pressuring Valentinian to leave his court in Mediolanum (Milan) and join him in his Gaulish capital, Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier). “A father and son” relationship, is how he proposed it… but the intent was clear - an attempt to appropriate the younger man's government. When Valentinian persitently refused this underhand grab for power, Maximus set about swelling his already strong Western armies, raising numerous new regiments and inviting Germanic tribes into his ranks too. Young Valentinian recognised the growing threat. So, in late AD 387, he dispatched Dominus the Syrian ambassador to Maximus’ capital. According to the early Byzantine chronicler, Zosimus, Maximus apparently charmed the diplomat out of his wits, convincing him to take a set of 'gift' legions back to Valentinian's court: "Maximus conferred on him so great honours, and so many presents, that Domninus supposed that Valentinian would never again have so good a friend. To such a degree did Maximus succeed in deluding Domninus, that he sent back with the Syrian part of his own army, to the assistance of young Caesar against the Barbarians." Zosimus’ accounts of what followed are vague. He seems to suggest Maximus, with the rest of his army, followed Domninus the diplomat and the 'gift' legions back through the Alpes and tricked or forced his way through the garrisons there, then penetrated deep into Italia, before seizing Africa too. Valentinian and his mother, Justina, fled east by ship, arriving at the port city of Thessalonica to plead for help from Emperor Theodosius. First, Theodosius sent stern demands for Maximus to relinquish his conquests. Next, he mustered the armies of the East, including a portion of the settled Goths recently settled in Roman Thracia. He also arranged for detachments of Hun, Alani and Iberian foederati to assist them. With the army assemled come the summer of AD 388, he then marched to war with the West. War!Nobody truly wanted this. The last comparable civil clash had been Emperor Constantius' suppression of a Gallic usurper Magnentius thirty years prior, an expedition that had exhausted the empire militarily and financially for many years afterwards. But Maximus’ aggression and seemingly insatiable territorial expansion meant war was unavoidable. Maximus established an advance army at Siscia (modern Sisak), a city strongly fortified by the River Savus (Save), with the intent of blocking Theodosius' landward line of advance towards Italy. His general, Andragathius, was stationed with strong forces on the approaches to the Julian Alps, while his brother Marcellinus lay in waiting with a third reserve army in nearby Noricum. Theodosius and the main body of the eastern army set off along the Via Militaris to meet Maximus' land-blockade at Siscia head-on. Meanwhile, Valentinian and Justina led a smaller band of legions by sea, behind Maximus' lines, to Rome. Valentinian first evaded a last-moment naval ambush led by Andragathius, then landed in Sicily, defeating Maximus’ troops there, before going on to claim the ancient capital. There was also a third prong of attack, with a contingent of soldiers sailing from Egypt to liberate the vital, grain-rich Diocese of Africa. Along the way with the main Eastern land force, Theodosius learned that some of the allied Gothic troops he had mustered by the terms of the peace deal of AD 382 had been bribed by Maximus. It is not clear whether they attacked the legions, sabotaged the march or simply deserted. All we know for sure is that he was denied the services of these tribal warriors. Meanwhile, the two main land forces of East and West finally met in a violent battle at Siscia. Theodosius’ cavalry and legions powered across the River Savus’ ford while Maximus’ defenders rained all manner of projectiles at them. The fighting was fierce, spanning two days and the night in between. Seeking reinforcements, and with General Andragathius absent in his failed attempt to intercept Valentinian at sea, Maximus instead called his brother, Marcellinus, and the reserve army to his aid, but he arrived too late. Thus, Siscia fell to the Easterners and Maximus withdrew. As Gibbon says: "After the fatigue of a long march, in the heat of summer, Theodosius and his army spurred their foaming horses into the waters of the Savus, swam the river in the presence of the enemy, and charged the troops who guarded the high ground on the opposite side." Theodosius pursued for several days until East and West clashed again on the plains near the city of Poetovio (modern Ptuj). This time Maximus was reinforced by the army of his brother. Yet it was not enough: "The enemy… fought with the desperation of gladiators. They did not yield an inch, but stood their ground and fell. Finally, Theodosius prevailed." After suffering this second successive reverse, Maximus retreated to the bulwark city of Aquileia, perhaps expecting to withstand a final siege. However, the quick succession of defeats had irreparably damaged the loyalty of his troops. When Theodosius’ advance guard arrived at the city, Maximus was handed over to them and - as described at the start of this piece - was summarily executed. His head was taken on a tour of the provinces. His son, Victor, was slain by Theodosius’ high general, Arbogastes. Dragathius, still hiding out at sea having failed to halt Valentinian, heard of his master's demise and threw himself into the deep. Hero or Tyrant?So it was an ignominious end for the once promising young commander, Maximus the Spaniard. Was he a Roman hero or a megalomaniacal tyrant? Although he saved Britannia from the Great Conspiracy earlier in his career, he certainly left the island in a bit of a predicament, stripping away the majority of its garrison in order to fuel his wars of ambition against Gratian. AD 383, the date he set sail with the British troops, coincides with the end of any evidence of Roman military presence in Wales. However, coins dated later than this have been found along Hadrian's Wall, suggesting that at least a skeleton garrison remained. And he seems to have remained a charismatic and popular figure to the people of Britannia whom he left behind. The Welsh legend of Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (English: The Dream of Emperor Maximus), recounts how Maximus marries a British woman (creating an imperial British bloodline), and gives her father sovereignty over the island (formally transferring authority from Rome back to the Britons themselves). Later lore also identifies him as the founding father of the dynasties of several medieval Welsh kingdoms, including those of Powys and Gwent. This does not fit with the picture of Maximus being tyrannical, or 'abandoning' Britannia. His reputation on the continental side of the channel does not hold up so well, with his broken oath and attack on Valentinian. Did envy and greed get the better of him? And his keeping of Gratian's body unburied and the murder of Bishop Priscillian - are these deeds as grim as they sound... or were they exaggerated by his opponents in the wake of his demise? Whatever the answer, Emperor Theodosius might have thought that by ridding the world of Magnus Maximus, the Roman Empire would know peace once more. But, as with so many ruinous wars, victory left a void of power in the West. And as we know all too well... power hates a vacuum.

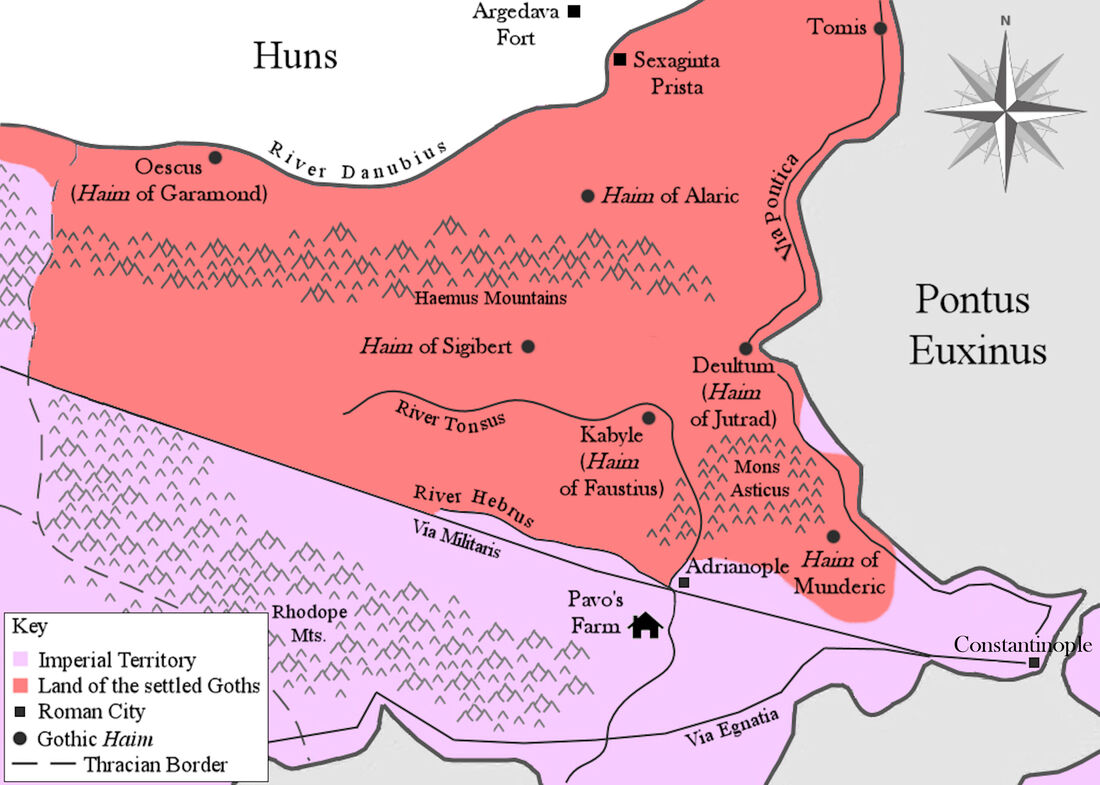

"It was an immense slaughter, greater than had ever occurred in any former naval action. Thus the river was filled with dead bodies." As winter fell in AD 386, the Eastern Roman Empire found itself in a position of delicately-balanced stability. The Gothic War had ended four years prior, thanks to a peace deal that granted the Goths Roman lands in the northern parts of the Diocese of Thracia on which to settle and farm. In return for this, their fighting men were to muster for imperial military service if and when Emperor Theodosius called upon them. This system of gradual cultural integration and laying aside of old grievances was only just beginning to settle into place. So, the last thing Emperor Theodosius needed was for a huge host of erstwhile unknown Goths to descend from the north and appear at the River Danube, demanding entry into the empire. The early Byzantine century historian, Zosimus, is our main source for the sequence of events. "Odotheus, who had levied an immense army, not only among the nations upon the River Danubius, but among others situated in unknown countries at a great distance, which he was then leading to the river." The new Gothic arrivals, under their king or high chieftain, Odotheus (or Aedotheus, as Zosimus names him), arrived at the river's northern banks in their multitides. The Roman legions, under the command of General Promotus, were hastily marched to and arrayed along the southern banks. The Goths then proceeded to petition the Romans for permission to cross the river - in this era unbridged - onto Roman soil. Odotheus impelled the Romans from the far banks, arguing that he and his followers had no choice but to seek new homes in the empire - for if they were to remain in the wild north, they would surely fall inder the yoke of the ever-more powerful Huns. Yet the Eastern Empire could not simply open up to such a mass of newcomers: a new immigration of this scale so soon after the Gothic War (which itself had been caused by a the poorly-handled immigration of 376 AD) could have wrecked the whole framework of cooperation. On Odotheus argued for permission to cross... with the tacit threat of invasion if this was refused. The Roman response finally came one moonless night. Taking advantage of the poor visibility, General Promotus secretly sent Gothic-speaking Roman agents across the river to bribe Odotheus’ noblemen, asking them to convince their chieftain of a false situation: that the Roman watch was lax this night and that he should seize this opportunity to try to force his way across immediately. Yes, the agents argued, it would mean defeat and death for their leader, Odotheus. But the noblemen were also assured that, after the action, the empire would recognise them as the new leaders of the tribes. The nobles accepted the bribe and approached Odotheus. He took the bait, rallying his people and, in the dead of night, in almost complete darkness, setting across the river in a huge flotilla of crafts. The late 4th century AD poet, Claudian, describes their fleet as 'three thousand vessels strong'. They must have felt invincible. When they reached midriver, everything changed. The Roman watch was anything but lax. General Promotus, lying in wait, sprung his trap. A fleet of Roman galleys, three tiers deep and twenty stadia wide, came speeding out to assault them. As Zosimus describes it: "The night being dark and without a moon, the Barbarians were unacquainted with the preparations which the Romans had made, and therefore embarked with great silence, supposing the Romans to be ignorant of their design. When the signal was made, the Romans sailed up to them in large and strong ships with firm oars, and sunk all that they met, among which not one man was saved by swimming, their arms being very heavy." Zosimus describes how "Promotus then sent for Emperor Theodosius, who was not far from thence, to witness his brave exploit". This implies that the Eastern Emperor was somewhere close to, or even in the Roman camp, but that he might not have been fully aware of Promotus’ ruse. When Theodosius arrived on the scene of this one-sided this slaughter, it seems that he was horrified rather than impressed. More, he realised that it might forever make enemies of these new Goths and alienate and trigger revolt in those already settled in his lands by the 382 peace deal. Accounts suggest he not only called off the assault, but also waded into the shallows to help the wounded Goths ashore. Apocryphal, probably, but a striking image nonetheless. Fraught as the whole incident had been, it was, nonetheless, a victory for the Eastern Empire. And there was more good news to follow: the tense talks that had for several years been rumbling between the empire and Persia about the division of Armenia was finally agreed, ending the air of uncertainty on that eastern flank. Harmony in the East, stability in the north. And with the Western Roman Empire by its side, the East would find no trouble in that direction... ...until Magnus Maximus arrived on the scene - read all about the momentous history that folowed here! After a 3 year hiatus, the XI Claudia march again, in...

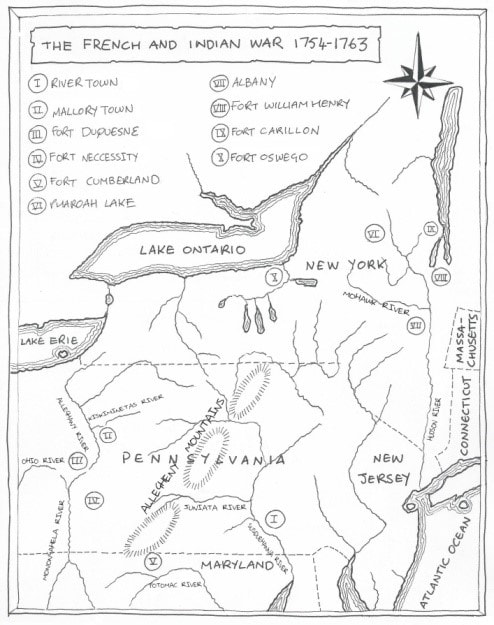

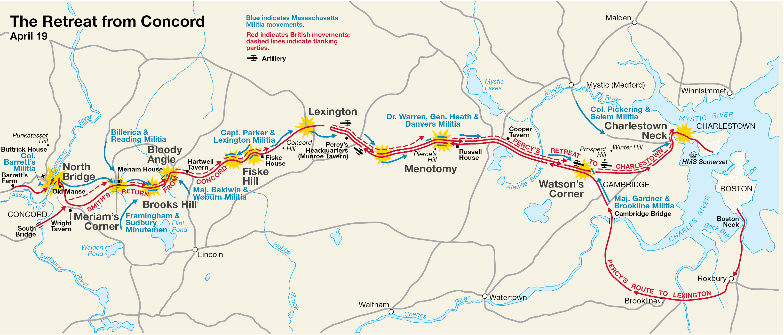

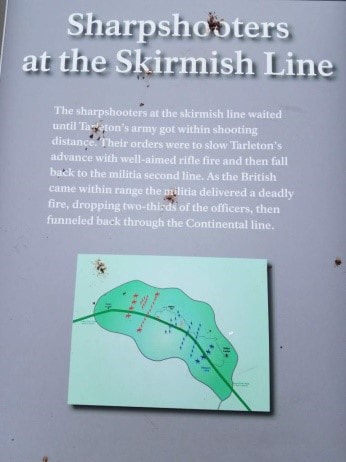

LEGIONARY: THE EMPEROR'S SHIELD! Coming 16th Feb 2023! I'm delighted to welcome my friend and fellow scribe onto the blog today. Paul Bennett blew me away with his tale of the French Indian War and the ensuing fallout. The Mallory Saga is top-notch historical fiction, and Paul is here to tell you all about it. Take it away, Paul! :) The Humble Scribe Paul Bennett - my stateside buddy and American history expert. Paul Bennett - my stateside buddy and American history expert. I am a retired (recently) data center professional. Not that I started out thinking I would spend nearly 50 years working in mainframe computer environments. My major interests, scholastically, in high school, and college were history, and anthropology. The Cuban missile crisis, Bay of Pigs, assassinations, Vietnam, Watergate, etc., were some of the events that shaped me, forming the basis for my cynical view of government. One of the results of this “hippie attitude” was that I quit school, and my job, taking a year and a half off to travel a bit, and enjoy life. During that period I began composing the odd poem or song lyric, but I knew in my heart, and from experience writing school term papers, final exams, and the like, that I was a prose writer. My favorite fantasy for my future at the time was to become a forest ranger sitting in some fire watch tower writing the great American novel. Life intervened, however, and I put that dream aside to marry, and raise a family, which meant I needed to be employed, thus decades of staring at computer screens ensued. As time went on, I began writing about the golf trips I took with my buddies. At first they were humor laced travelogues, but now they are fictional tales of my friends; the golf becoming a vehicle for creating a story. Then in 2013, I started writing book reviews, and communicating with authors about the process of writing a novel. My dream to write the great American novel returned. The Adventure Begins...The inspiration to write was, in the beginning, merely to see if I could do it. I had written short pieces over the years but to tackle a full blown novel was a daunting prospect. Once the seed was planted I came up with a rough idea of telling the story of three siblings living somewhere in colonial America. Choosing that general locale was a natural fit for me as I’ve been a lifelong student of American history and I felt that if I was going to write a historical fiction novel, it might be prudent to choose a subject I knew a little about. I picked The French and Indian War as the starting point for what was now becoming a possible series of books that would follow the Mallory clan through the years. That war intrigued me and I saw a chance to tell the story through the eyes of the Mallory family. It also provided me with the opportunity to tell the plight of the Native Americans caught up in this conflict. The French and Indian War paved the way for the colonies to push further west into the Ohio River area. It also set the stage for the events of the 1770’s. Britain incurred a huge debt winning that war and looked to the colonies for reimbursement in the form of new taxes and tariffs. Well, we all know how those ungrateful colonists responded. As to the name Mallory – I have a photo hanging on my living room wall of my great grandfather, Harry Mallory. I got to know him when I was a young boy and was always glad when we visited him. He lived a good portion of his life in western Pennsylvania which is where much of Clash of Empires takes place. So, as a gesture to my forebears, Mallory became the name of the family. Clash of EmpiresIn 1756, Britain and France are on a collision course for control of the North American continent that will turn into what can be described as the 1st world war, known as The Seven Year’s War in Europe and The French and Indian War in the colonies. The Mallory family uproots from eastern PA and moves to the western frontier and find themselves in the middle of the war. It is a tale of the three Mallory siblings, Daniel. Liza and Liam and their involvement in the conflict; the emotional trauma of lost loved ones, the bravery they exhibit in battle situations. The story focuses on historical events, such as, the two expeditions to seize Fort Duquesne from the French and the fighting around Forts Carillon and William Henry and includes the historical characters George Washington, Generals Braddock, Forbes and Amherst. The book also includes the event known as Pontiac’s Rebellion in which the protagonists play important roles. Clash of Empires is an exciting look at the precursor to the events of July 1776; events that will be chronicled in the second book, Paths to Freedom, as I follow the exploits and fate of the Mallory clan. Paths to FreedomIn Paths to Freedom the children of the three Mallory siblings begin to make their presence known, especially Thomas, the oldest child of Liza and Henry Clarke (see right there, already another family line to follow), but Jack and Caleb, the twin sons of Liam and Rebecca along with Bowie, the son of Daniel and Deborah are beginning to get involved as well. The French and Indian War, the historical setting for book 1, was over, and the Mallory/Clarke clan is looking forward to settling and expanding their trading post village, Mallory Town, now that the frontier is at peace. And for a time they had peace, but the increasing discontent in the East, not so much toward the increasing rise in taxes, but the fact that Parliament was making these decisions without any input from the colonies, slowly made its way west to the frontier. Once again the Mallory/Clarke clan would be embroiled in another conflict. Another facet of my saga is that the main characters are not always together in the same place or even the same event. In Paths my characters are spread out; some have gone East, some have gone West, some are sticking close to Mallory Town, so in effect there are three stories being told, and that means more plots, subplots, twists and surprises. One of the aspects of the lead up to The Revolutionary War was the attempt by the British to ensure cooperation with the Native Americans, especially the Iroquois Confederation. The British had proclaimed that they would keep the colonies from encroaching on tribal lands, a strong inducement indeed. However, some tribes, like The Oneida, had established a good relationship with the colonists. I knew right away when I started book 2 that the relationship between the Mallory’s and the tribes would be part of it. Among the historical Native Americans who take part in Paths are the Shawnee Chiefs; Catecahassa (Black Hoof), Hokoleskwa (Cornstalk), Pucksinwah (father of Tecumseh), and the Mingo leader Soyechtowa (Logan). I also realized that I needed to get someone to Boston, and the Sons of Liberty. Thomas Clarke, the eighteen year old son of Liza and Henry, was the perfect choice for the assignment (mainly because he was the only child old enough at the time). J Through him we meet the luminaries of the Boston contingent of rebels, Paul Revere, Dr. Joseph Warren, John Hancock, and the firebrand of the bunch, Sam Adams. Plenty of history fodder to be had…British raid in Salem…Tea Party…the famous midnight rides…culminating with the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Oh yes, plenty of opportunities for Thomas. An untenable situation arises in Mallory Town resulting in Liam and his two companions, Wahta and Mulhern, finding themselves on a journey to the shores of Lake Michigan and beyond. Driven by his restless buffalo spirit, Liam has his share of adventures; encountering a duplicitous British commander, meeting many new native tribes, some friendly, some not so much. A spiritual journey in a land not seen by many white men. I ended Paths with the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the first shots of The Revolutionary War. The flint has been struck; the tinder has taken the spark. Soon the flames of war will engulf the land, and the Mallory clan will feel the heat in the third book, Crucible of Rebellion. Crucible of RebellionThe timeline for Crucible is 1775 – 1778. I decided to split the Revolutionary War into two books, mainly because there is so much more action as opposed to The French & Indian War…and because as I was writing, my characters insisted on some scenes I hadn’t previously thought of. J Book 4 of the saga is in the planning stages. Tentative title – A Nation Born. The three Mallory siblings, Daniel, Liza, and Liam play important parts in CoR, but it is their children who begin to make their marks on the saga. Their youngest son, Ethan, and their daughter Abigail, of Daniel and Deborah travel with their parents to Boonesborough, and reside there with Daniel Boone. The war reaches even this remote frontier, prompting Daniel and Deborah to move further west in search of peace. However, the banks of The Wabash River prove not to be immune to conflict. Their eldest son, Bo accompanies Liam’s twins, Jack and Cal, first to Fort Ticonderoga, then to Boston with a load of cannon for General Washington’s siege of Boston (the Noble Train of Artillery with Colonel/General Henry Knox). In Boston they meet up with Liza and Henry’s son Thomas, who is no longer a prisoner (can’t say more than that) J, Marguerite, and Samuel Webb. General Washington has plans for the Mallory boys…plans which see some of them in a few of the more important battles of the war… the escape from Long Island, the surprise attack at Trenton, the turning point battles at Saratoga NY, as well as taking part in numerous guerilla type skirmishes. A long ways away from the conflict Liam, with Wahta, are living with the Crow along the Bighorn River. Liza and Henry made the trip to Boonesborough with Daniel and Deborah, but do not go with them to The Wabash….they have their own adventures. A Nation is BornA Nation Is Born - book 4 of the saga covers 1779-1781 As the Revolutionary War shifts south, and west, so too, the Mallory’s find themselves right in the thick of it. On the banks of the Congaree River in South Carolina, and on the Wabash in the Northwest Territory, war is not the only problem they face. Revenge stirs among the embers of war. At the battles of Cowpens and Guilford Court House in South Carolina, and the retaking of Fort Sackville on the Wabash River, the Mallory's are tried and tested. Emotions run high in this tale of revolution and self-determination. Although I write fiction tales, the historical aspect of the saga provides the backdrop. History is often overlooked, or is taught with a certain amount of nationalistic pride, whitewashing controversial events, much to the detriment of humankind. So I hope that what I write might help broaden the reader’s horizon a bit, that what they learned in school isn’t necessarily the whole story. Two main historical topics in the story of America that frequent The Mallory Saga are slavery, and the plight of the indigenous people who have lived here since before the founding of Rome; two historical topics that linger still in America’s story. Entertainment and elucidation; lofty goals for a humble scribe telling a tale. A Turbulent BeginningA Turbulent Beginning – book 5 - 1788-1795 The Revolution is over, and a new nation has emerged from the ashes of war. The new government, leery of a powerful central government, learns quite quickly the folly of state legislatures controlling military operations, abandoning The Articles of Confederation to write The Constitution. More lessons are learned by this second attempt when they discover that the indigenous tribes along the Ohio were more than a match for militia troops. It is time for President Washington and his War Secretary Henry Knox to come up with a better plan to pacify the warring tribes. The Mallory clan is spread out from the Congaree River in South Carolina to the Wabash River in the Northwest Territory. The desire to be together again is stronger than the fear of traveling through a war zone. They are once again in the middle of the storm…can they survive…can they make a difference? The Jagged MountainsThe Jagged Mountains – book 6 – 1783-1808 In The Jagged Mountains, I took a slightly different approach to this entry into The Mallory Saga. Not only is it partly in first-person it is also a tale with very little historical content. When I started thinking about how to present Jack’s quest, I decided to make it as personal as possible. Using a first-person narrative for Jack gave my Muse free rein to delve into how Jack responds to the challenges he faces; his thoughts, his fears, and his joys. As for the historical aspect, or lack thereof, that really excited my Muse. She loves to color outside the lines so to speak, so in this tale, she had a blank page to fill with her imaginative whims. Obviously, there was no Raven Army that rampaged through the plains and mountains, but the idea of a pan-Indian alliance is not a farfetched one. Indeed, as you’ll learn in book 7, one of the more formidable confederations of tribes arises under Tecumseh. Then of course in 1874 another tribal alliance destroys the 7th Cavalry. Well I hope I’ve piqued your interest in American historical fiction, and in particular The Mallory Saga. If so moved, the buy links are below. Crucible of Rebellion paperback will be out soon. Follow the progress of The Mallory Saga here:

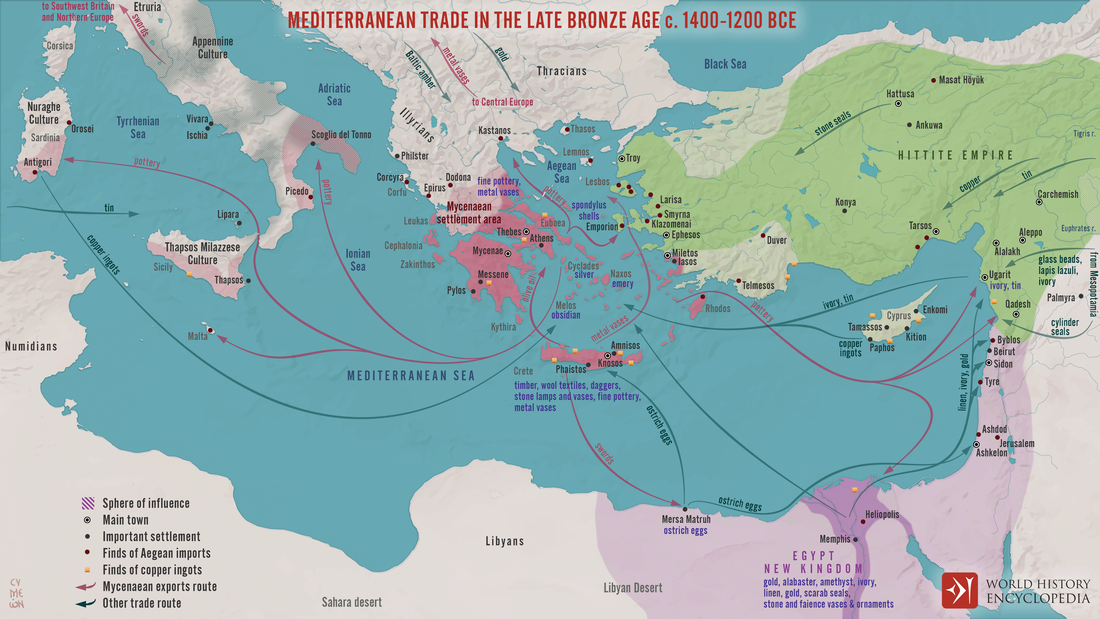

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/mallorysaga Mallory Saga Wordpress Blog: https://clashofempires.wordpress.com/ Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B087T5DWRB The Bronze Age began around 3,300 BC. It was an era in which the near eastern world knew stability. The mighty Empires of Egypt, Assyria, The Hittites, Babylon, Mitanni and Mycenaean Greece dominated the map, underpinning a thriving 'palace' economy. The eastern Mediterranean would have been thronged with trade boats and the overland routes packed with mules and wagons, carrying to and fro all sorts of ancient commodities: iron, silver, tin, copper, lead; horses, wool and textiles from the Hittite lands; gold and scarab jewels from Egypt and turquoise from the Nile deserts; slaves from Nubia; jasper & Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan; jewellery and perfumes made in Crete by Minoan artisans; oil and wine from Greece. There were also famous wars between these rivals, but also great peace pacts too. For the peoples of these times, it must have seemed like the ebb and flow of things, as if the empires were eternal, and that the ways of the Bronze Age would last forever. Then, around 1200 BC, everything changed.... It is for good reason that we refer to that period as ‘The Bronze Age Collapse’ – a catastrophic end of an epoch, in which many of the great empires were blown away in a storm of destruction. The aftermath was truly bleak. Civil order gave way to chaos. The delicately balanced trade networks crumbled to nothing. The palace economy (a fragile, dangerously overspecialised system) vanished, to be replaced a few centuries later by dark age Greek village economy. Literacy collapsed – ushering in an age of oral tradition which gave rise to the likes of the Trojan War legend. What caused this collapse? The likelihood is that it was triggered by not one, but many causes. Firstly, the 13th century BC was a time of drought, as palaeoclimatologists have discovered. Pollen samples indicate a long-lasting dry spell, stretching all the way from northern Turkey to the northern Nile Delta. More, tree ring examinations show 5 or more years of uncharacteristically low rainfall in Anatolia. The Hittite tablets confirm this with accounts of drastic crop failure and starvation. They also detail the remarkable deal struck between the Hittite Great Queen, Puduhepa, and the Egyptian Pharaoh, Ramesses II, to arrange relief shipments of grain from Egypt to the Hittite realm. Ramesses also sent his best irrigation experts to attempt to revive Hittite soil, but to no avail – the Bronze Age dams at Arinna and other Hittite sites across Anatolia date to this time and may have been part of these irrigation efforts. Secondly, tin – the crude oil of its day – was growing scarce. Without tin, the armies could produce no bronze, and without bronze, they could no longer flex their muscle in the same way as before. This was most probably the driving force behind the Hittites’ apparent experimentation with iron in the last few generations of their time. Iron ore was plentiful around their Anatolian heartland, and promised to equal or even better the strength and durability of bronze. Thirdly, seismologists have found evidence of an 'earthquake storm' that gripped the near east for most of the 13th century BC. With the Hittite heartlands sitting smack-bang on the fault lines of Anatolia, they suffered the brunt of this. The Hittite capital of Hattusa, the cities of Troy (a close Hittite ally) and Karaoglun all show evidence of seismic trauma. In Greece too, we see evidence of earthquake damage at the ruins of a whole host of key cities: Mycenae, Tiryns, Midea, Thebes, Pylos, Kynos, Lefkandi, Menalaion, Kastanas, Korakou, Profitis Elias, Gla. And in the levant, the cities of Ugarit, Megiddo, Ashdod and Akko have the same characteristic damage. So too Enkomi on Cyprus. Fourthly, we come to the Sea Peoples. Who, I hear you ask? Some believe they were a fierce horde of northwestern invaders who blazed and razed their way across the near east world in a frenzy. Others would say they in fact arose from within the empires of the time. Some claim they were in fact an unmanageably huge tide of refugees, driven to seek new lands by the drought. The origins of the Sea People is an almighty tangent, which I explore more fully in this companion blog article. All we know is that they arrived in – or possibly arose from – the near east world… and proceeded to churn it into oblivion in two major waves, the first a mainly coastal movement, the second one plunging deep inland. Within a period of forty to fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the twelfth century almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was violently destroyed, many of them never to be occupied again. These four factors - drought, tin shortage, earthquakes and invasion - combined to tear down the landscape of civilization and bring the Bronze Age to an end. The Hittite Empire* and the Mycenaean world were wiped from the face of the earth, while a battered Egypt and a much-reduced Assyria limped on into the Iron Age. *One tiny Hittite enclave survived, giving rise to the lesser Neo-Hittite Kingdoms.

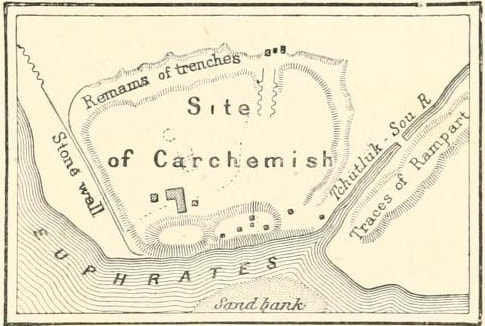

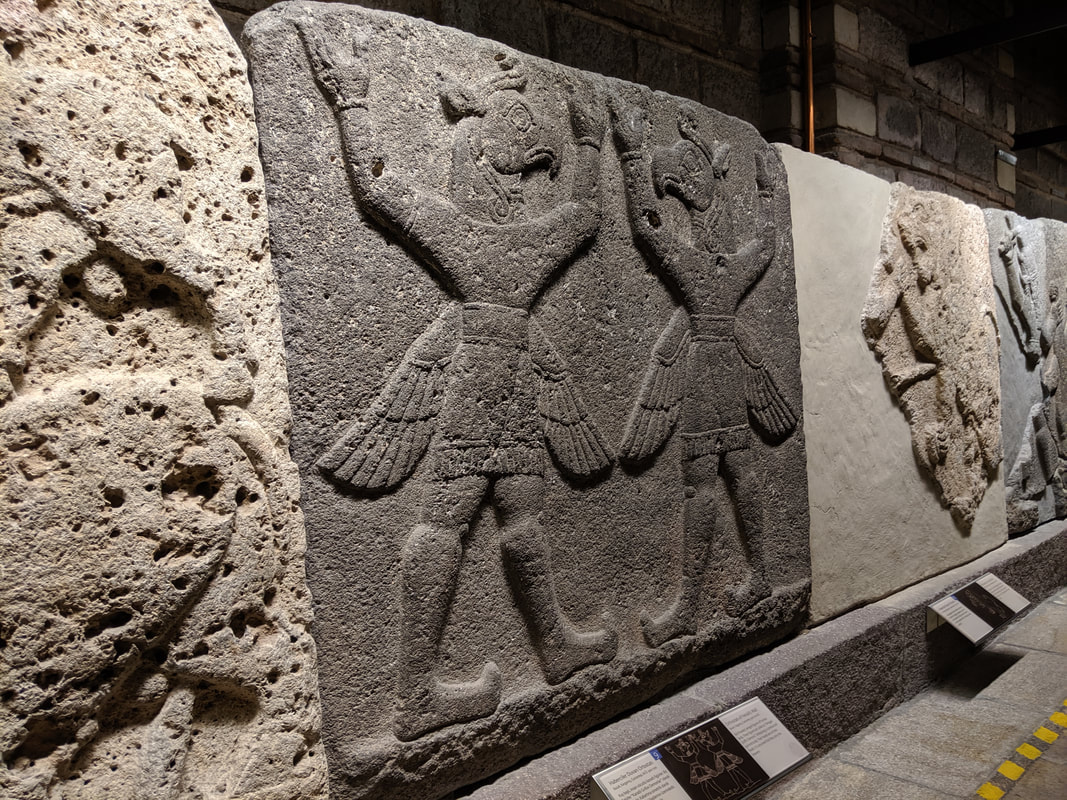

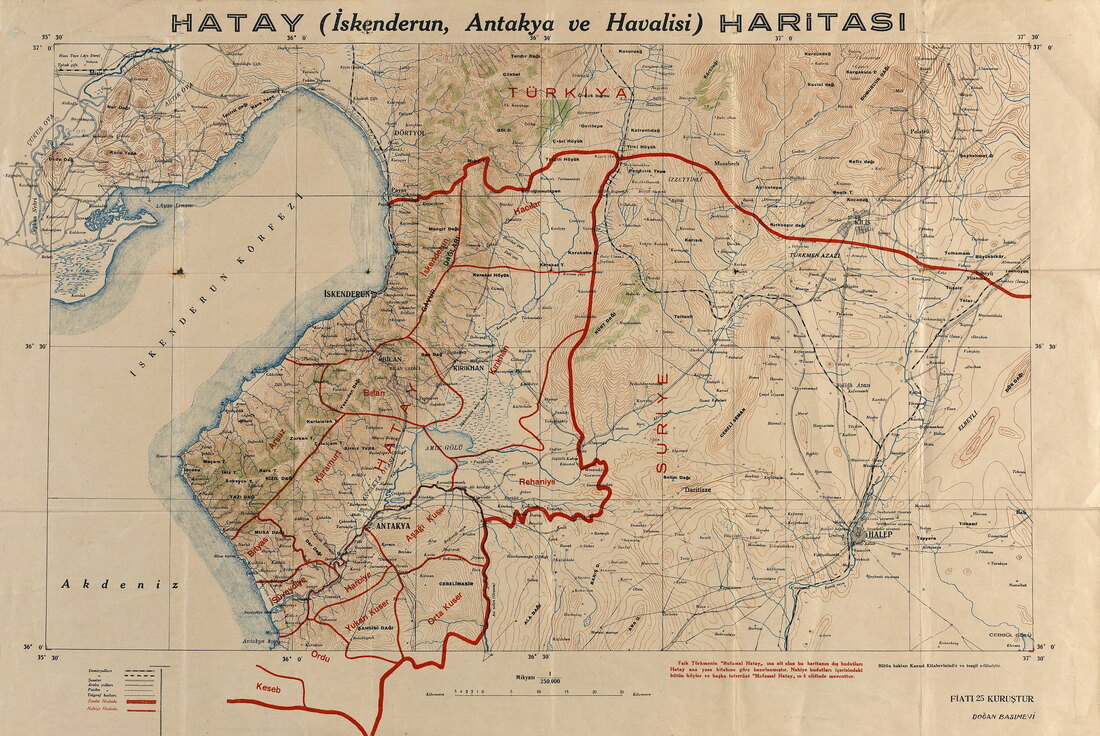

Around 1200 BC, the great Hittite empire and Mycenaean Greece were swept into oblivion in a series of natural disasters and the ruinous march of the Sea Peoples. We call this period the Bronze Age Collapse. While the empires of Assyria and Egypt endured the collapse, albeit in a much-reduced state, the world afterwards entered a dark age of sorts. Literacy vanished across Greece and the Hittite Empire, and the complex political infrastructure of the Bronze Age's heyday became a forgotten art. From this smoky aftermath new, smaller kingdoms gradually arose all around old Hittite and Greek lands. In Greece, a people known as the Dorians came to the fore and flourished, many centuries later, as the Greeks of the Golden Age (think Athens, Plato, Pericles et al.) In Anatolia - the vast old Hittite heartland - the Phrygians, the Carians and the Kingdom of Urartu rose to prominence. But the Hittites had not vanished from history completely. In the last throes of the Bronze Age Collapse, a small group of Hittites (sensibly) fled their old lands, leaving behind their ancient capital of Hattusa and heading east in search of shelter. They came to northern Syria, and specifically the river city of Carchemish - once a mere border viceroyalty of the Hittite throne, ruled by one of the king's cousins and far from the Anatolian heart of the empire. Now, the city was all that remained. Carchemish became - in effect - a life raft for Hittite culture and custom, preserving them through the Sea Peoples' devastations and the ensuing dark age. Geographically, Carchemish made for a perfect safehaven - fortified, and shielded on one side by the River Euphrates, it had a reputation for being 'unbreakable'. Indeed, It had for centuries previously served as something of a Hittite border fortress and a perfect vantage point to guard a ford across the Euphrates and to watch for any military activity over on the (Assyrian) far banks. More, sited over 100 miles from the Mediterranean coast, it was comfortably distant from the shore attacks of the Sea Peoples, and far enough up-country to be missed by the brunt of their later inland assaults. This enclave of refugees did endure, and went on to form what we call the Neo-Hittite Kingdoms - a collection of allied mini-states. Indeed, circa 1100 BC - around one hundred years after the Sea Peoples had faded from the scene - the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser, refers to Ini-Tesub, the king of Carchemish, as a "King of Hatti" (in other words, the King of the Hittites). In another inscription, while passing through the city of Malatya - a good one hundred miles north of Carchemish - Tiglath-Pileser identifies it as being "in the land of Hatti", so the Hittite enclave had clearly expanded. Some of the relief art found at Carchemish is quite striking - clearly a blend of the original Hittite style mixed with the artistic flair of their near neighbours (and eventual conquerors) the Assyrians. Examples can be seen below: And of course, we soon arrive in the Biblical era, where the Canaanites, Abraham and Hebron, speak of a strange hill people in the near north. They describe these people as the "Sons of Heth" (Heth being the name of a patriarch amongst the hill tribes), or "The Hethites". Indeed, it is from this Biblical reference that we get our modern name "The Hittites" (the people we call Hittites actually referred to themselves as "The People of the Land of Hatti"). Hittite rule in that small northern Syrian kingdom did not last forever, eventually falling prey to the resurgent Assyrians by the 8th century BC. However, the echoes of their ancient culture remains to this day. Indeed, the Republic of Hatay ('Hatti') - the most southeastern province of modern Turkey and situated around Neo-Hittite lands - is but one quiet echo of the greatness that once prowled around Anatolia and Syria, some 3,000 years ago.

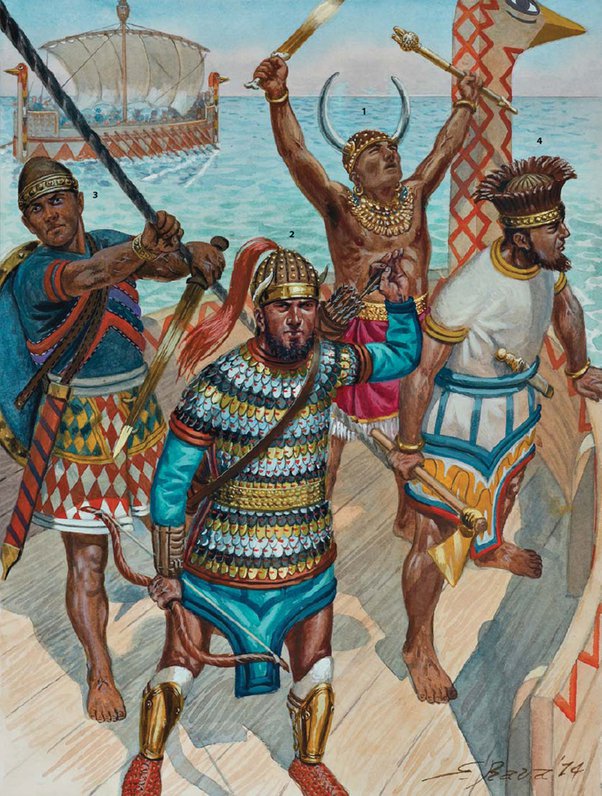

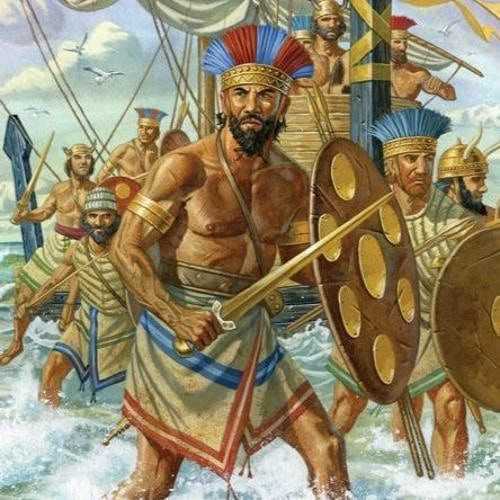

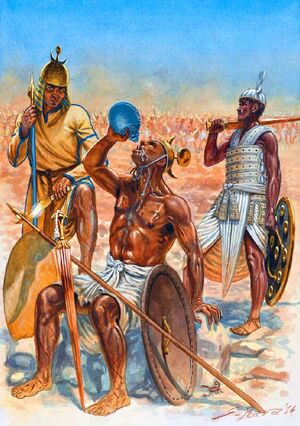

Around 1200 BC, a great migration of peoples occurred - a shadowy multitude of many different tribes and cultures who roved violently across the near east upon a mighty fleet of bird-prowed ships. The Egyptians - one of the few powers who survived their assaults - dubbed them as 'the Sea Peoples'.  A depiction of the Sea Peoples by the inimitable Giuseppe Rava. Here we see 1: a priest; 2. an aristocrat; 3 & 4. warriors of the 'Ekwesh' - one of many tribes amongst the Sea Peoples mass. A depiction of the Sea Peoples by the inimitable Giuseppe Rava. Here we see 1: a priest; 2. an aristocrat; 3 & 4. warriors of the 'Ekwesh' - one of many tribes amongst the Sea Peoples mass. Amongst the many Sea Peoples tribes were: The Sherden, The Peleset, The Ekwesh, The Teresh, The Lukka, The Shekelesh, The Meshwesh, The Kariska, The Denyen, The Tjekker, The Weshesh (yes, many of those names sound like they should be pronounced with no teeth in!) Together, this huge host descended from the north and the west in a series of waves, and proceeded to churn the near east into oblivion. Within a period of forty to fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the twelfth century almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was violently destroyed, many of them never to be occupied again. The Timeline of DestructionThe First Wave, circa 1230 B.C

The Second Wave, circa 1200 B.C.

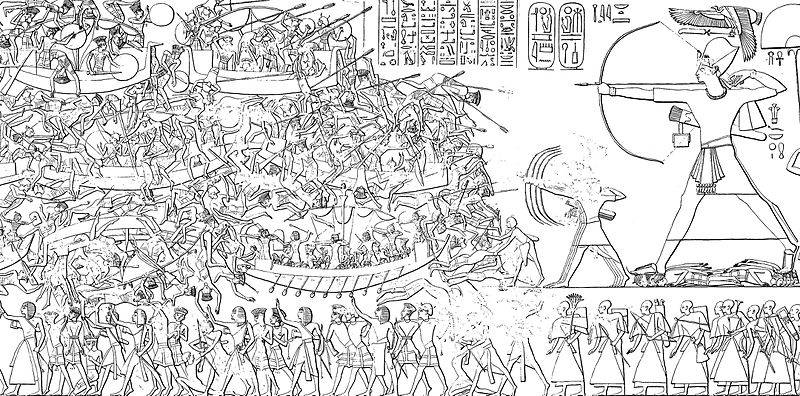

"The people were disturbed in their islands. All at once nations were moving and scattered by war. No land stood before their arms, Not the Hittites, Cilicia, Carchemish, Arzawa nor Cyprus. They were all laid to waste. They desolated the people of Amurru, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming for Egypt. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjekeru, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh lands united. They laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: ‘Our plans will succeed!"  The reliefs at Medinet Habu, showing Ramesses III and his Egyptian forces fighting off a huge swell of Sea Peoples at the Battle of Zahi. Puzzlingly, while Ramesses' associated writings identify five Sea Peoples tribes being involved, these accompanying representational scenes seemingly represent only two (Horned Sherden and feather-hatted Peleset or Lukkans). Who were the Sea Peoples?This is probably one of the most enigmatic questions in history, and while I certainly don't expect this blog to provide a definitive answer, I hope my speculation proves interesting. The Sea Peoples origin theories range from:

I can state with some confidence that the Sea Peoples were not, as per the first theory, "Bloodthirsty Invaders". We must remember that this happened in the decades known as the Bronze Age Collapse, a time when - amongst other things - a mighty drought had gripped the world. The starvation attested by the Hittite tablets would have been widespread across much of Europe and the near east. If anything, hunger is likely to have been the thing that spurred the Sea Peoples to march in search of food and a better home. In other words, they were almost certainly a symptom of this Collapse, not a cause. Most plausibly, they were a loosely united host of tribes and states struck earliest and hardest by the drought and the storm of ruinous earthquakes that accompanied it. E.g. the peoples in Greece, Thrace and western Anatolia, and even those from Italy, Sicily and Sardinia too. In short, a mix of the "Great diaspora" and the "Greek Diaspora". Indeed, there are some depictions of what looks like Greek armour and the Egyptian depictions of the Sea Peoples - see the section at the end of the blog for imagery. I should pause to point out that, while most historical discussions (this blog included) tend to focus on the destruction associated with the Sea Peoples, this does not mean that they were a violent people per se. In my opinion, the violence that followed the Sea Peoples' advance was most probably just another sad repetition of how mass migrational movements - of hungry and frightened people - often play out. Desperation and a stark lack of charity inevitably lead to conflict. Now, let's have a look at the individual tribes associated with the Sea Peoples' movement: The TribesThere are many speculative theories on the identities of the individual Sea Peoples tribes. What follows is a selection of the most interesting, along with a few of my own takes: The Sherden The Sherden are probably the most famous of the Sea Peoples factions, distinguished by their distinctive horned helmets. They had been involved in small-scale piratical raids on the eastern coasts for generations before the age of collapse. Indeed, the legendary Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II even retained a small guard unit of Sherden. He said of their earlier, smaller raids: "The unruly Sherden whom no one had ever known how to combat, they came boldly sailing in their warships from the midst of the sea, none being able to withstand them. But where did they come from? All we know from Ramesses III's writings is that they originated north of Egypt. Pretty vague! They may have originated from Sardinia (Sherden-ia), or perhaps they later settled there, giving that island their name and ending their days of migration and raiding. The Shekelesh In 8th c BC - some four centuries after the Bronze Age had ended - Greeks colonising Italy arrived on the island of Sicily. Here they encountered a group called the Sikels, whom they believed had come to Italy after the Trojan War (which probably occured very close to or during the Bronze Age Collapse and the Sea Peoples' movement). Perhaps these Sikels arrived in Sicily and gave the island its name after the collapse... or maybe the island had always been the home of the Sikels, and these ones the Greeks met were the indigenous remnant - the ones who had not set off on the Sea Peoples' movement. Reliefs suggest the Shekelesh warriors carried two spears and no shield, wore a gold medallion, and a bronze skullcap or cloth headdress. The Lukka Fairly easy one this - the Lukkans originated from the region in southwestern Turkey, known in the later Classical Age as 'Lycia'. It seems that the Lukkans were somewhat wild - a people with no king, but many tribes. Bordering on Hittite lands, they were at times friendly with the Hittite King, other times not so much. Also, as legend has it, the Lukkans came to Troy's aid in the Trojan War. The likelihood is that the Lukkans either rose in support of the Sea Peoples' movement, or - more likely in my opinion - were swept along by it (after having their already drought-stricken lands ravaged by the invaders, there wasn't much option but to join them) The Denyen / Danuna There is a strong likelihood that the Denyen were the core of the Mycenaean Greek refugees. In The Iliad, Homer sometimes referred to the Greeks as "Danaans" - a term supposed to cover all of the many city states that Agamemnon had mustered for his siege of Troy. The Peleset There are a few theories as to the origins of the Peleset - Crete and Anatolia being two mooted homelands. Generally it is thought that they originated somewhere in that region. I personally can't help but see the similarity in the name "Peleset" with the Greek city state "Pylos". This is just more conjecture, but with so little evidence to work with, it is not implausible. Also, the feathered tiaras the Peleset wore can be plausibly linked back to the southern stretches of Greece (where the city of Pylos was). Interestingly, after the Battle of Zahi, some Peleset were taken captive in Egypt and settled in Pharaoh's northeastern border regions to farm and patrol those lands. These people eventually became known as the Biblical Philistines. The Weshesh, the Tjekker & the Teresh I've grouped these three together because there are theories associated with each that they *might* have been Trojan diaspora, possibly swept along in the Sea Peoples' movement in the same way the Lukkans were. That they fought with short swords, long spears and round shields and sported 'hoplite-like plumes' on their helmets suggests they might have originated from Trojan/Aegean lands at least. Also, a mummified Teresh servant found in the court of Ramesses III still shows fair hair, sugesting he was most probably not of Egyptian or African origin. The Tjekker might have been:

The Weshesh might have been:

The Teresh might have been:

Maybe none of these three groups were Trojans, maybe all were. We will never know for sure. Yet legend remains that one Trojan group - having survived the Trojan War - then went on to escape the Sea Peoples' rampage and the fall of the Bronze Age. Eventually , as the story goes, they settled in northern Italy, founding the Etruscan civilization from which Rome would one day rise. With this in mind, one can consider another theory - given the similarity in the names - that the Teresh might have been the refugees from the fallen Greek city of Tiryns. I'm playing with possibilities here, but legend also has it that Diomedes, King of Tiryns and a key Greek player in the Trojan War, also sailed to northern Italy after the Bronze Age Collapse, and was something of a rival to the Trojan settlers there. All of this is hopefully food for thought. Please do leave your comments below. Thanks for reading!

🍾🍾🍾It's publication day for 𝐄𝐌𝐏𝐈𝐑𝐄𝐒 𝐎𝐅 𝐁𝐑𝐎𝐍𝐙𝐄: 𝐓𝐇𝐄 𝐃𝐀𝐑𝐊 𝐄𝐀𝐑𝐓𝐇!

★★★★★ Praise for the Empires of Bronze series:

To celebrate launch week for my new book THE DARK EARTH, here's another wee excerpt.

This piece - nicknamed "The Cyclops' Prophecy" takes place after Tudha and his Hittite soldiers have captured the coastal city of Milawata - a long-time Ahhiyawan (Greek) stronghold and bridgehead on the Hittite mainland. It should be a triumphant moment, but not all is as it seems... ‘What happened here?' Tudha said, casting his eye across barren Milawata. The city had not been in Hittite hands for many years, but even now that it was, it did not feel like a prize. Walmu shifted his straggly hair back from his bruised and cut face, his expression sagging. ‘The slave traders fled this place some time ago. The people – sensing trouble – quickly followed.’ ‘Trouble?’ ‘Something is going on across the Western Sea in Ahhiyawa. Some great disaster has struck their rocky lands.’ Tudha felt a twist of unease in his belly. He and his men gazed out across the sea and its bands of gradually deeper blue, as if in hope that they might see something as far away as the distant Ahhiyawan realm. He eyed that silent, unmoving horizon of deep water and infinite skies. So peaceful, still and empty. The Ahhiyawan Kings who had conquered Troy had vanished back across those waters, never to return. It was as if the Gods had swept them away. ‘How do you know of what has happened over there?’ Walmu’s face twisted a little. ‘The Cyclops. He speaks of grim things.’ Tudha arched an eyebrow. ‘The Cyclops? You speak of things you have seen or heard in visions, dreams?’ ‘No, my lord,’ explained Walmu. ‘A flesh and blood creature. Frightful to look at. He appears near the resettlement at New Troy from time to time, professing that all across the Western Sea is in chaos. He always finishes with a prophecy.’ Walmu’s green eyes suddenly became shrouded in worry. ‘That the disaster that struck Ahhiyawa is now coming this way...’ Tudha’s war wolf growled. Old Dagon’s eyes widened. Skarpi and Pelki leaned in to listen, so too did many of the Hittite soldiers nearby. ‘…for him, for us, for you… for everyone.’ Tudha stared through Walmu, seeing instead the Goddess Ishtar as she had come to him in his dreams, hearing her words. 𝐺𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑡 𝑐ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑖𝑛𝑔, 𝑇𝑢𝑑ℎ𝑎, 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑦𝑜𝑢𝑟 𝐻𝑖𝑡𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑒 𝑤𝑜𝑟𝑙𝑑 𝑙𝑖𝑒𝑠 𝑑𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑙𝑦 𝑖𝑛 𝑖𝑡𝑠 𝑝𝑎𝑡ℎ... |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed