|

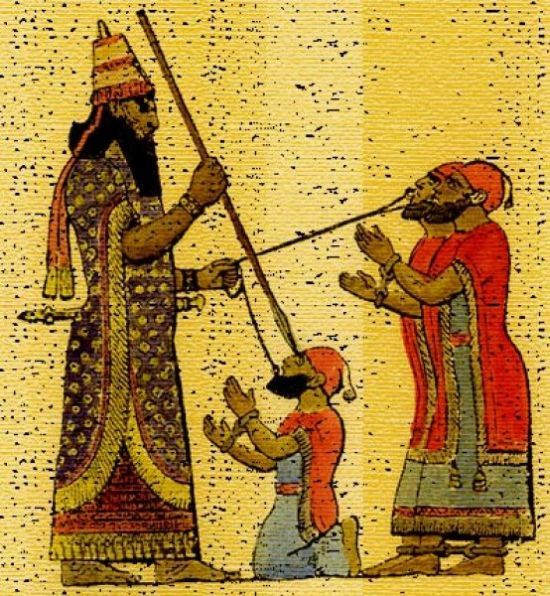

In the early years of the 13th century BC, the Hittite Empire had known decades of prosperity, military success and expansion... and most importantly of all harmony in the throne room. This last virtue was thanks to a long-standing tenet of Hittite civilization, written by an old king named Telepinu. The 'Edict of Telepinu' declared that the Labarna (King) was the appointee of the Hittite Gods and that his rule was not to be disputed. More, taking up arms against the current incumbent of the Hittite throne was the darkest of crimes. Yet in 1267 BC, the Hittite Empire turned in upon itself, collapsing into a state of civil war. Why? The reigning Labarna, Urhi-Teshub, was a young king, not long upon the throne. His uncle, Hattusilis (or Hattu for short), was some twenty years older and for a generation had been held in the highest regard by the Hittite people - as a battle hero, a great priest and a talisman for their civilization. Most vitally, he acted as a strong advisor to his young nephew. Yet early in Urhi-Teshub's reign, tensions emerged between the pair. The young king began removing old allies of Hattu from the court, and putting in their place men who had clear axes to grind with his uncle. For example, Urhi-Teshub:

Why all this tinkering? It is likely - indeed, quite understandable - that Urhi-Teshub saw Hattu as a potential threat to his throne, given his uncle's status. The strain may have escalated during one incident of state, specifically an unfortunate and abrasive visit to the Hittite court of an envoy from the neighbouring superpower of Assyria. The matter was this: vassal raiders from Hittite lands had spilled into Assyrian territory. Adad-Nirari, the Assyrian King of the time, had chased down the raiders, encroaching and camping upon Hittite lands in the process. Now Adad-Nirari was rather brashly suggesting that the encroached-upon territory should remain his. Even the suggestion must have been a serious affront to Urhi-Teshub's credibility. Might his advisors have been whispering that the Assyrian King would not have dared to insult Hattu, the older, more experienced hand, in this way? We don’t know exactly how Urhi-Teshub reacted, but we do know the Assyrian envoys were not exactly thanked for their message. One of the tablets uncovered at Hattusa is a copy of that addressed to Adad-Nirari, and mentions that: “The ambassadors whom you regularly sent here in the time of King Urhi-Teshub often experienced ... aggravation” (Bryce, Letters of the Great Kings). Once the embassy had left, it appears that Urhi-Teshub turned his unbridled anger upon Hattu. The young king began stripping his uncle of estates, soldiers and titles. One day, he went too far, depriving Hattu of the governorship and priesthood of northern cities that he had fought to capture many years before. This was the breaking point. Hattu, in another tablet, wrote: "For seven years I submitted. But … Urhi-Teshub sought to destroy me. (Eventually), he took Hakmis and Nerik from me. Now I submitted to him no longer. I made war upon him." Thus, civil war was afoot. The two factions mustered what support they could. At a time when the Near East world was bruised and battered and still licking its wounds from the Battle of Kadesh in which many troops - men of working age, vital to crop production - had been killed or injured, this new war threatened to upend the already delicate political and economic Bronze Age landscape. It would certainly mean yet more death and destruction... but possibly on a scale that neither aggressor could ever have imagined. Empires of Bronze: The Crimson Throne will take you back to the distant Bronze Age, right into the heart of this ancient conflict and through all its sharp twists and turns.

1 Comment

|

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed