|

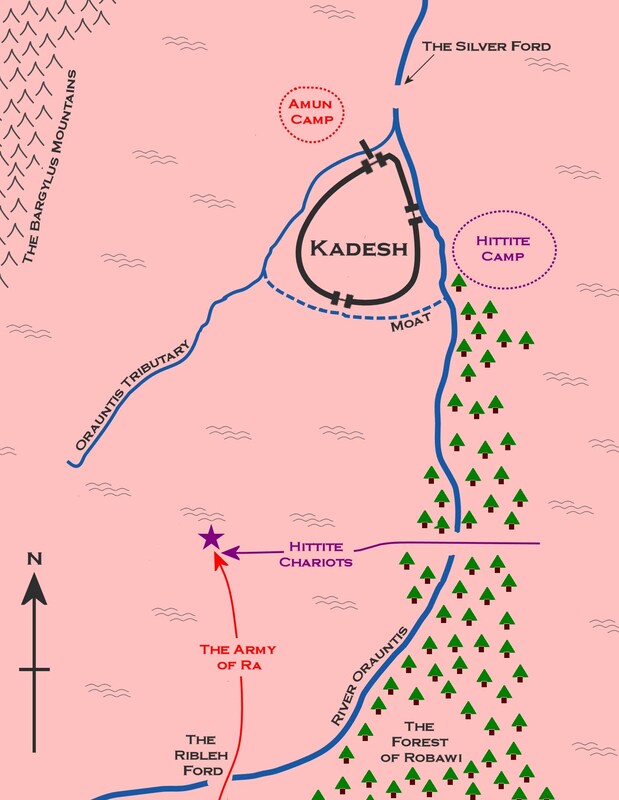

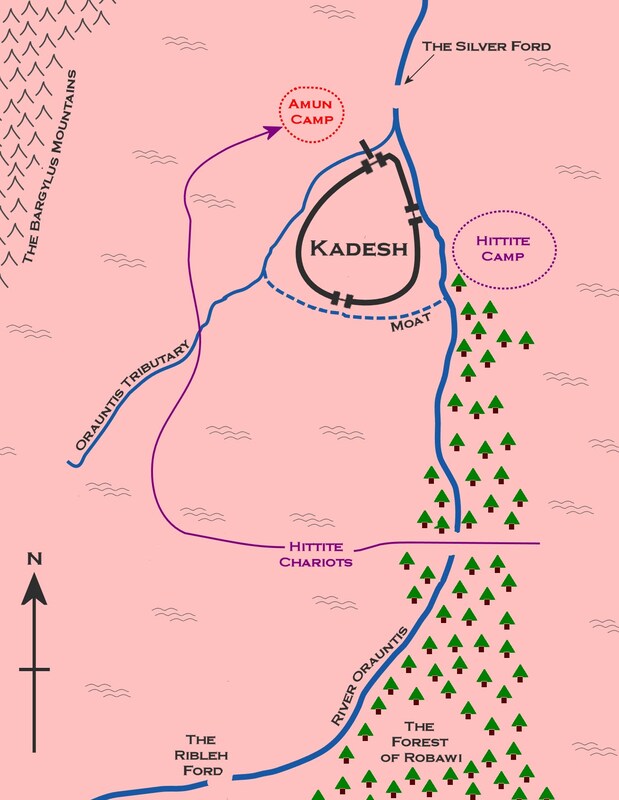

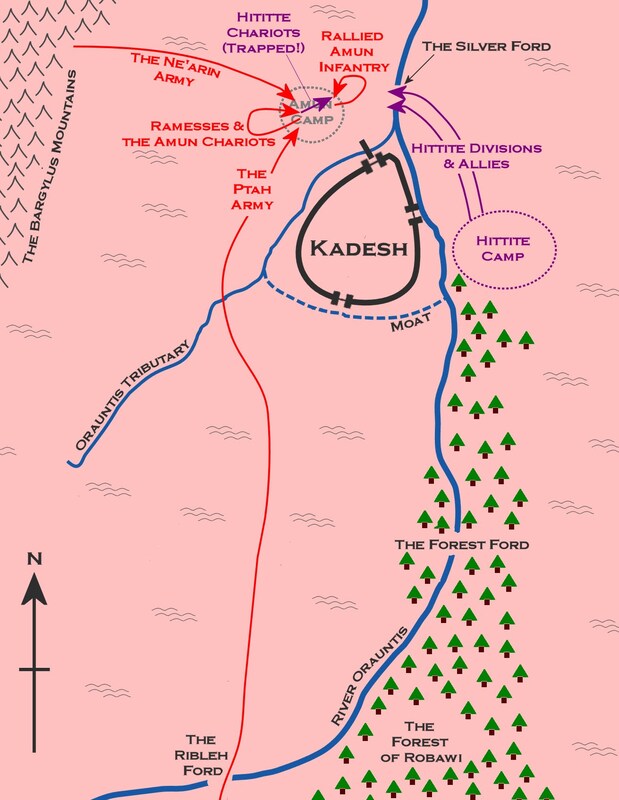

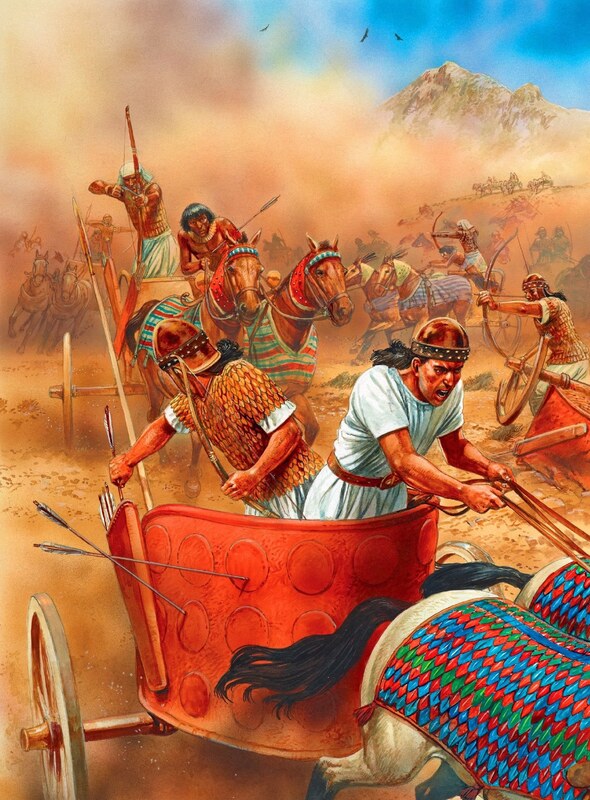

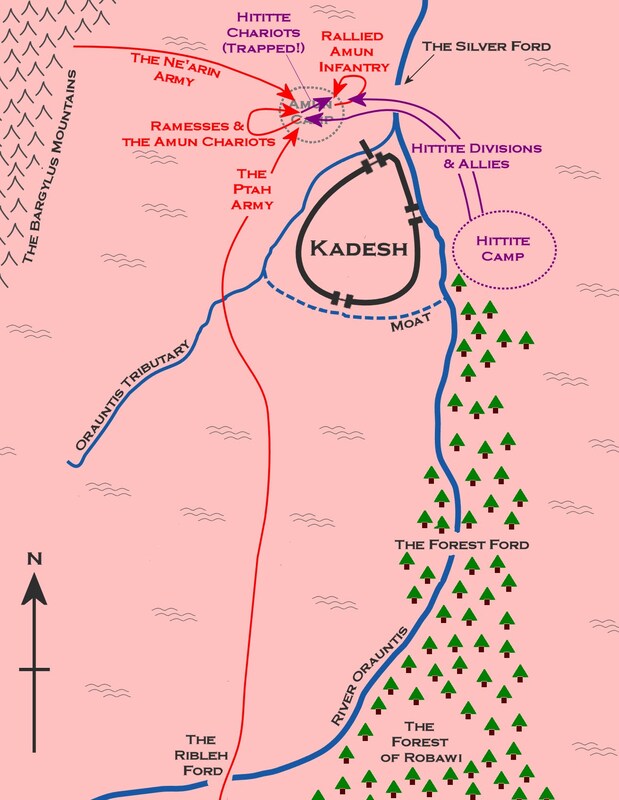

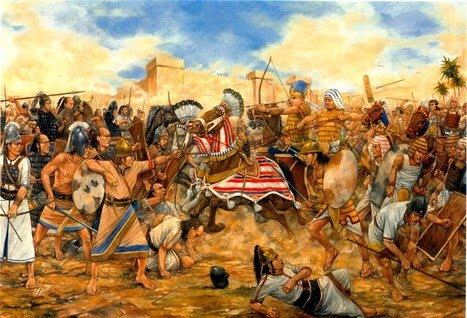

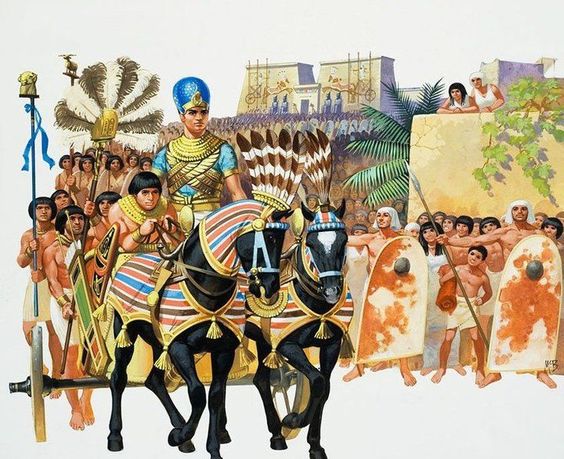

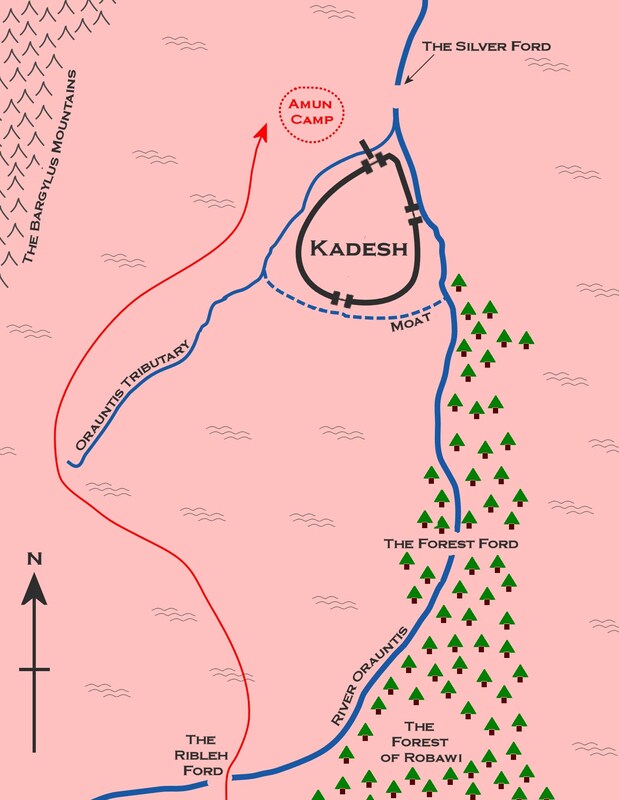

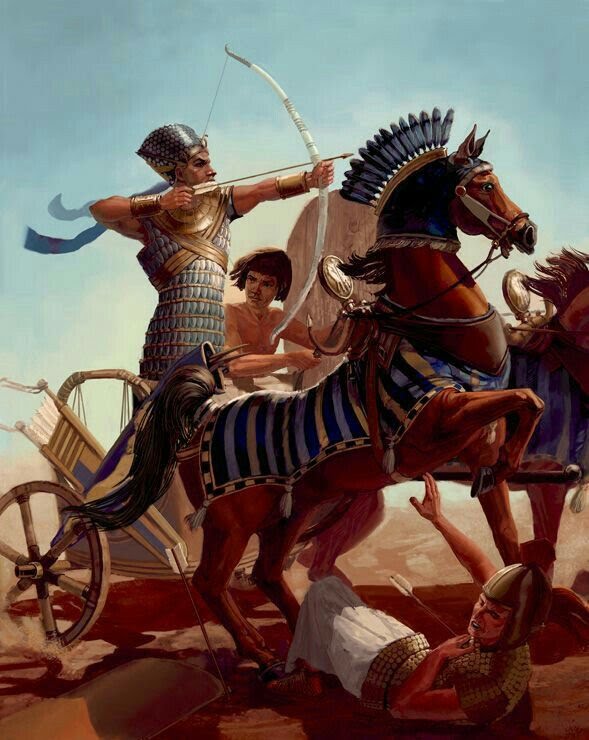

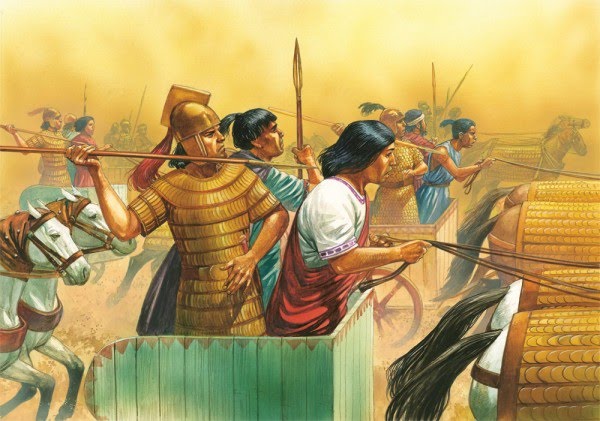

In part 2 of this blog, we followed the march of the Hittites and the Egyptians as they converged upon the city of Kadesh. We left off with Pharaoh Ramesses and his Amun Army encamped northwest of the city, triumphant that they had reached it before their rivals... only to be struck dumb by the news that the Hittites were in fact here already, concealed behind the eastern side of the Kadesh mound. Now we plunge into the depths of the oldest battle on record... Ramesses' Reaction and the Fate of the RaPharaoh Ramesses, alarmed and enraged that he had been tricked, sent one of his viziers off to the south to warn and hasten his other three armies. There was still time to gather his forces, he must have thought. At this point in time - the last stages of dawn - the closest of his three trailing armies was the Ra. They were led by one of Ramesses’ sons, and had just crossed the Ribleh Ford (see map, below). As they marched north, they would have passed the Forest of Robawi on their right flank, still completely unaware that the Hittites were anywhere near this land... ... and then the veils of deception dropped. From the woods, a horde of Hittite chariots - possibly as many as two or three thousand of them - exploded into view in a blaze of light, slicing through the last curls of dawn mist. These carefully-crafted three-man vehicles led the charge, with swarms of allied chariots alongside - some even from Troy. Prince Hattusili (Hattu) is likely to have led this strike. It was a devastating attack: they hammered into the Ra flanks and obliterated that force, sending many fleeing back to the south. It was a fine and thorough triumph. More importantly, they had effectively cut Ramesses and his Amun Army off from three-quarters of his entire campaign force. Deception!Or was it? It is still a matter of debate: when the Egyptians arrived at Kadesh, were they suddenly ambushed by the hidden Hittite forces as I have described above? Or was it more of a strategic surprise, i.e. did Ramesses reach Kadesh and see from a safe distance that the Hittites were already there, having arrived unexpectedly early? As a writer of historical fiction, it would take a strong and compelling case for me to go with the latter theory, and in truth, the stronger and more compelling cases I have read support the former anyway. Some argue that if it was truly an ambush, it would have been a notable, almost anachronistic twist in the art of war; for it is thought that such trickery was not the norm for major conflicts of that era. On the other hand we are without detail of any other battles of the time, so one must challenge that assumption. We do know that the Hittites celebrated and studied deceptive tactics, such as the myth of Sargon’s surprise attack and capture of the city of Purushanda, so there are plausible grounds for the Kadesh ruse being a true and well-laid ‘ambush’. If it indeed was a surprise attack, then the Hittites executed it brilliantly, and the Battle of Kadesh was well and truly underway. The Destruction of the Amun CampAfter routing the Army of Ra, Prince Hattu then turned his chariot host northwards, swinging across the shallow Orauntis tributary and speeding towards Pharaoh's Amun camp. Within the vast and as-yet incomplete camp, Ramesses would no doubt have heard a strange rumble in the south, then noticed the heat-warped horizon there shaking and sparkling… before the Hittite chariots exploded into view, coming straight for them. By all accounts, the Hittites ripped the Amun camp to shreds, surging over the half-finished earth & shield rampart and harrowing through the sea of tents and men within. Pinned by this chariot assault from the southwest, and unable to retreat across the Orauntis thanks to King Muwa and his forty thousand strong Hittite infantry force guarding the far riverbanks, Pharaoh was trapped. The historian J.H. Breasted suggests the Hittite infantry ‘plugged’ the fording points of the Orauntis and denied Pharaoh any route of escape that way. Indeed, accounts tell of heavy fighting in the river shallows. So, trapped between this infantry anvil and chariot hammer, Ramesses found himself on the cusp of a complete rout. Egyptian accounts claim the Hittites were stopped from claiming this full victory only because of their greed – with some of their chariot crews stopping so they could load up with Egyptian treasures. Looting was a common part of ancient warfare so it is not unlikely, but one would think that if the Hittite chariotry were on the cusp of a complete victory then they might – having marched across the world to get here – complete that rout first before stopping to pick up jewels and trinkets. Whatever the Hittite chariots were doing, the Amun Army apparently rallied. The Egyptian chronicler Pentaur describes Pharaoh in the midst of it all, riding his chariot alone, reins lashed around his waist, bow in hand: "The serpent that glowed on the front of his diadem ‘spat fire’ in the face of his enemies." But spirited fightback or not, the Amun were looking doomed. Until the sound of horns rose in the west... The Coming of the Ne'arinFrom the western mountains, a huge Egyptian reinforcement army known as ‘The Ne’arin’ appeared and sped into the battle. The origins of the Ne’arin are foggy to say the least. Some speculate that they were the soldiers of the close-by land of Amurru. Others suggest they might have been Pharaoh’s rearmost army – the Sutekh – having secretly stolen up the coastal road ahead of the Ra and the Ptah to be nearer to Kadesh than the Hittites expected. In Thunder at Kadesh, I have opted for a combination of these two theories – that the Ne’arin were a vassal horde of Amurrites, Gublans and Canaanites and that they arrived with the expedited Sutekh alongside them for good measure. These forces relieved the Amun soldiers and began to overwhelm and pulverise Prince Hattu's Hittite chariotry. More, from the south the Egyptian Ptah Army was now across the Ribleh Ford and speeding towards the fray. The balance of battle had well and truly swung in favour of Egypt. The Hittite Counterattack and the Coming of DuskKing Muwa, seeing the death-trap in which his brother Hattu and the Hittite chariotry were ensnared, led a reserve of chariots and elite soldiers into the fray, probably across a ford north of Kadesh (the 'Silver Ford' in my diagrams). These forces collided with the ongoing fray on the site of the already ruined Amun camp and the battle raged on throughout the day. Egyptian records describe their Sherden mercenaries hacking the hands from Hittite casualties as some kind of ‘kill-tally’. Pharaoh’s war-lion, Foe-slayer, was there on campaign with him and no doubt played a part in the fray too. The action ceased only when the light began to fade and both armies began to peel apart. After a full day of battle, nothing had been decided. The Hittites still held Kadesh and the eastern banks of the Orauntis, while the Egyptians dominated the western banks. The Remains of the DaySo, in the blackness of night as both sides gathered up their dead and kept an anxious watch on their rivals across the Orauntis, another day of battle must have seemed certain. But then, most unexpectedly, some kind of talks took place either that night or early the next day... and it was all over. Never again in history did Egyptian and Hittite swords clash. "Hold on," I hear you shout. ''You can't leave it there! What happened in the talks? Who 'won'?" So Who Won the Battle of Kadesh?Egyptian reliefs – carved into the walls of the temples at Karnak, Luxor and Abydos – describe the Hittite King falling to his knees and begging Pharaoh for mercy, presumably at these mysterious talks. Apparently, Pharaoh mercifully agreed to this, and the two armies went their separate ways. Following this account, it sounds like we have an Egyptian victory, doesn’t it? Well, until fairly recently, historians thought so (while also acknowledging the partisan nature of Egyptian accounts). That seems only fair, given there were no other source materials to contend with this view. However, in modern times, more than thirty thousand tablets have been discovered under the ruins of the Hittite capital, Hattusa, and some of these shed a rather different light on things. It seems that the Hittites clearly considered themselves to be the victors of Kadesh and of the talks. And an objective analysis does support this, for we now know that immediately after the battle, Pharaoh withdrew his armies from Kadesh, leaving it in Hittite hands, and also – tellingly – pulled his garrison out of nearby Amurru, ceding that vital neighbouring region to the Hittites after twenty years of occupation. The Hittites then claimed further lands ot the south in Pharaoh's wake. Ramesses and his armies headed back south to Egypt having won not a patch of land and having lost a great deal of it. In any case, if the Hittites did truly ‘win’ the Battle of Kadesh it was in many ways a Kadmean victory, with great losses incurred: some seven allied kings and huge swathes of allied and Hittite men died over the course of that full day of combat. The consequences of the victory were enormous, for the Hitittes and Egyptians remained at peace throughout the remainder of their time as contemporary powers, and even signed a formal defensive alliance some years later. But the history shows that this was a bad time for the Hittites to have weakened themselves so grievously. Indeed, dark ramifications lay ahead... Thanks for Reading!I hope you enjoyed this blog series. Any questions? Leave a comment below or get in touch - I'd be delighted to hear from you. Also check out my other blog post which looks at the Hittites' 3-man chariots, the 'secret weapon' that helped give them the edge at Kadesh.

And remember, the whole journey can be lived out in visceral detail in the Empires of Bronze series! Book 3 Thunder at Kadesh follows the build up to and execution of the battle you have just been reading about!

2 Comments

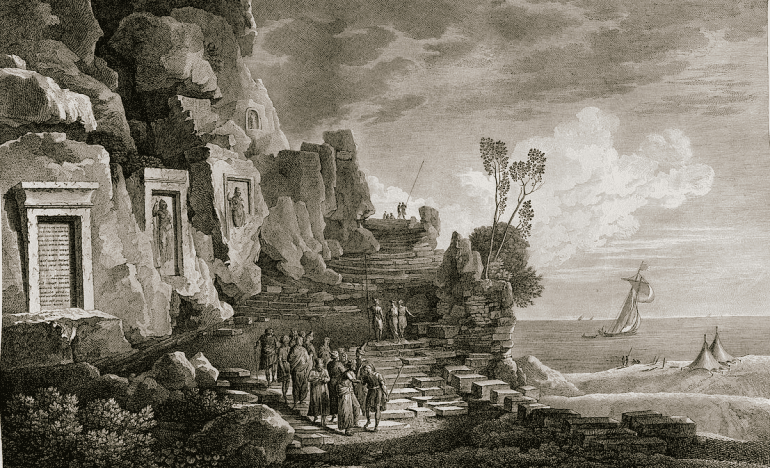

In part 1 of this blog, we followed the deterioration of relations between the Hittite and Egyptian Empires: a severe and irreparable collapse of diplomacy that led to their mutual declarations of war. In this second part, we will join the two great powers on their march across the ancient world towards the greatest showdown of the Bronze Age... But first, it is important to understand why King Muwatalli (Muwa) and Pharaoh Ramesses chose Kadesh as the place where they would fight out their differences. Why Kadesh?The River Orontes (Orauntis) rises in modern Lebanon and tumbles northwards through Syria, before finally crossing into southern Turkey and turning westwards to spill out into the Mediterranean Sea. Just north of the Lebanon-Syria border, the Orauntis is fed by a small tributary snaking in from the west. Nestled in the conflux of these waterways stands a mound known these days as as Tell Nebi Mend. The mound is large, high and dominant, giving an excellent and commanding view over the rivers and of the large expanse of flatland all around. This would have been an easy choice of site for a king or general looking to establish a stronghold, and scholars largely agree that the Bronze Age city of Kadesh once stood here. Choosing to fight a great battle in the countryside of Kadesh made sense for a number of reasons:

The Race for KadeshBoth sides knew that once the fair marching weather of spring 1274 BC arrived, it would be a contest of speed and shrewd planning to reach Kadesh first - for the Hittites to bolster the city and for Egypt to seize it before the Hittites arrived. March of the Egyptians Of the Egyptian march, we know most. Ramesses mustered his four great divisions - The Amun, the Ra, the Ptah and the Sutekh. Each of these forces numbered anything up to 10,000 men. Each was effectively a self-contained army, with their own archer companies, an infantry and chariot core, pack mules and supply wagons, medical staff, priests and scouts. These four divisions set off from Pi-Ramesses, Pharaoh's capital on the Iteru (Nile) Delta. Ramesses himself led his elite Amun Army, and was followed by the Ra, the Ptah and the Sutekh as they marched along the ‘Way of Horus’ – the Egyptian military road of conquest. They came to the great fortress of Tjaru, stopping to take supplies from the armoury there, before continuing on into southern Retenu. Delays would have been hard to avoid: hold-ups with supply trains, bandits, sandstorms. There are even attestations of Egyptian soldiers falling ill with fever after drinking directly from the cold streams there, or perishing of shock after wading in - and any such delays on this campaign would have been worrying for Ramesses given the challenge of reaching Kadesh before the Hittites. But on they went, past Migdol fortress and up the Gublan (Lebanese) coast, before bending inland at the Dog River (the modern Nahr al-Kalb, where 3,000 year-old inscriptions in the rock made by Ramesses’ soldiers still exist!). This took them into a highland region, and along the high Valley of Cedars. The River Orauntis cuts across the northern end of this valley in a deep gorge, and the Egyptians halted here to make camp for the night. From the gorge-side, Ramesses would have been able to look across the river and see the low, pan-flat countryside of Kadesh on the far side. His goal was in sight... but had he made it here first? March of the Hittites We know very little about the Hittite journey to Kadesh, but we understand that they were led by King Muwa and his brother, Prince Hattusili (Hattu) - who also served as a high general and Gal Mesedi (Hittite chief of state security). We can surmise that they would have first mustered their four core divisions (four because they seem to have had a system of four generals), each maybe five thousand strong. We know they also called upon the many vassal kings to support them. The Trojans, the Arzawans, the Dardanians, the Masans, the Seha Riverlanders, The Karkisa, the Lukka... the list goes on. Estimates vary, but it is generally accepted as plausible that they marched to Kadesh with 40,000 infantry and 2,500 chariots (specialist vehicles, each crewed by three men) in tow, giving a possible grand total of 47,500 soldiers. To the onlookers of the time it must have seemed like the entire world was marching to war. The Hittite Army would have set off along the upper of their two heartland highways. This would have led them eastwards across the centre of modern Turkey, then southwards past one speculative location of the city of Zantiya (historically known as Lawazantiya) of whom Ishtar was the patron deity, then on through the White Mountains (the modern Anti-Taurus range in southeastern Turkey), gathering up more vassal armies along the way. They would have emerged from the mountains to meet yet more allies at the northern edges of Retenu, including the small but stout Hittite armies of their two Viceroyalties of Halpa (modern Aleppo) and Gargamis. Finally, they would have speared southwards towards Kadeshi lands. Who Won the Race?While Ramesses was encamped at the gorge-side and within sight of the countryside of Kadesh, two Shoshu Bedouin tribesmen arrived from the wilderness and came to him. They explained that the Hititte army was still far away in the north, near Halpa (modern Aleppo). It was better news than Pharaoh could have hoped for. The city of Kadesh was within a day's striking distance. He could seize the city well before the Hitittes even reached these parts. But his thoughts must have been tinged with caution, for in his haste to reach Kadesh first, he had arrived here at the gorge camp with just his principal army, the Amun. Meanwhile, the Ra, Ptah and Sutekh were strewn out many miles in his wake. Some scholars debate that this was not rashness but prudence - leaving such a gap between armies would mean recources such as springs and pasture lands would have a chance to partially recuperate after one army had passed through, in time for the next to come by. Regardless, Ramesses' dilemma was the same: surge forth with the Amun Army and seize Kadesh, or waste precious hours, days even, waiting on the other three armies? Ramesses opted to set forth at dawn the next day, before his other armies had caught up. He crossed the Orauntis at the Ribleh ford and led the Amun Army past the flat tongue of land between the Orauntis and its tributary, coming round on the tributary's western side and skirting that waterway until the Kadesh mound rose into view in the northeast. Just northwest of Kadesh, he halted and ordered his Amun soldiers to make camp. The sun was still crawling over the horizon as his troops set about making a siege camp, demarcating a huge area with a low rampart of soldiers' shields dug into the earth. Meanwhile, Ramesses set about planning how he might take the city, and he must have done so with a growing sense of triumph - for he had met not a jot of resistance... It was here that Ramesses' day turned distinctly sour. His guards spotted two strange-looking soldiers hidden in nearby bushes, watching the Egyptian camp works. Captured and brought before Pharaoh, Ramesses realised they were Hittites. Forward scouts, he guessed, then ordered their interrogation. It must have been 'persuasive', because they soon revealed to him the news that surely turned his soul to ice... The Great Hittite Army was not in Halpa... the enemy was already here, hiding behind the eastern side of Kadesh's huge mound! Pentaur, Pharaoh's 'Poet Laureate' described the captured Hittites' confession as follows: "Lo, the king of Hatti has already arrived, together with the many countries who are supporting him . . . They are armed with their infantry and their chariots. They have their weapons of war at the ready. They are more numerous than the grains of sand on the beach." So who won the race to Kadesh? The Hittites, without question. And they were here in full, while Ramesses had just one-quarter of his forces with him. What happened next? Sharpen your swords and stay tuned for The Battle of Kadesh Part 3: Clash of Empires (coming soon) - where we delve right into the Fray! Hope you enjoyed the read. Any questions? Leave a comment below or get in touch - I'd be delighted to hear from you.

Around 1274 BC, the Hittite and Egyptian Empires clashed near the city of Kadesh - a battle of unprecedented scale and repercussion, and the first such major and direct showdown ever recorded. This 3-part blog aims to explore the battle that took place at Kadesh over three thousand years ago, and we begin here with the first question: in an age of nobility, careful diplomacy and respect, why did it come to such a brutal conflict? Why did the Hittite and Egyptian Empires go to war?By 1274 BC, the Hittites and the Egyptians had co-existed for some four centuries. The Hittites ruled most of modern-day Turkey and controlled a halo of vassal kingdoms on the Turkish coasts and in the northern Levant. Far to the south, the Egyptians held sway, their crop fields fed by the yearly inundations of the Nile and protected by the vast tracts of desert either side of that great waterway. The Egyptians too controlled many vassal lands near their home territory. Relations between Egypt and the Hittites were not always peaceful, it must be said. But prior to 1274 BC, aggression between the two states had only ever been in the shape of posturing and political dispute, as well as proxy war - with the Hittites compelling some of their vassal kingdoms to attack or obstruct an Egyptian army or trade route and vice versa. Not once in all that time had the huge and mighty armies of Egypt's Pharaoh or the Hittite Labarna (high king) been mobilised to face one another in full, all-out war. But a sequence of tit-for-tat exchanges soon changed that... The Build-up of TensionsHistory teaches us that most empires grow until they meet some form of resistance that checks their expansion. Think of Xerxes' Achaemenid Persia, swelling and thriving inexorably until it met with the Greeks at the Hot Gates then Salamis. Or Attila's Hunnic juggernaut, invincible until his armies came up against the allied patchwork of the fading Western Roman Empire and its 'barbarian' allies. So it was with the realms of Egypt and the Hittites. Both gradually stretched out to claim more and more territory as their own. There was a particular desire on both sides to possess the lands of the modern Levant, known to the Egyptians as 'Retenu' (see the dash-lined box area in the map, above) - a land veined with ancient trade routes. No trade was more important than that of tin; tin was a scarce resource, and being essential in the production of bronze, a vital one for any state with martial ambitions. For the Hittite Labarna and Egypt's Pharaoh, controlling Retenu and denying it to their opponent was a must. Here's a snapshot of the creeping territorial ambitions that brought the Hititte and Egyptian realms nose-to-nose in central Retenu:

Stay tuned for The Battle of Kadesh Part 2: The Road to War ! Hope you enjoyed the read. Any questions? Leave a comment below or get in touch - I'd be delighted to hear from you.

Warfare in the Bronze Age pivoted around the use of the battle chariot. The superpowers of the era - the Egyptians, the Hittites, the Assyrians and the Ahhiyawans/Greeks - all relied heavily on an elite corps of these explosively powerful devices. They were the tanks of their day. The main strength of the chariot was its mobility. A team of rampaging horses could spirit heavily-armed warriors across a battlefield many times faster than a man could run. In this era, chariots largely took the form of a two-wheeled cabin towed by a pair of horses.

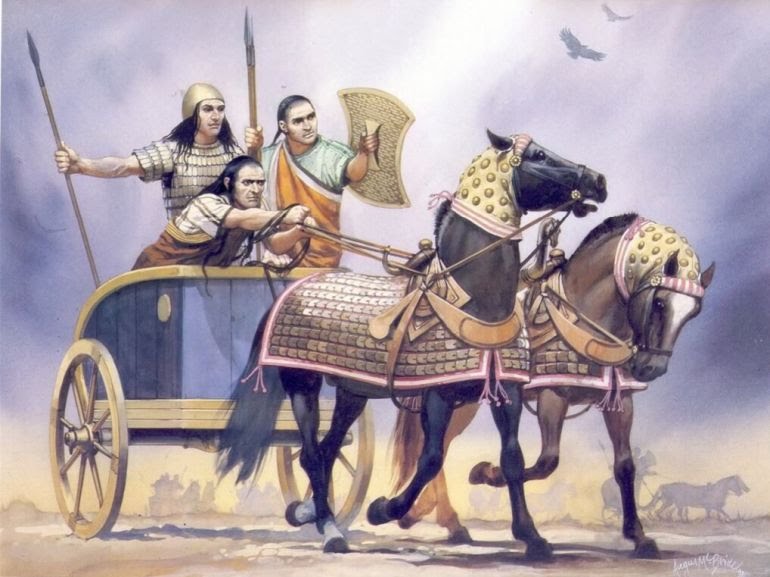

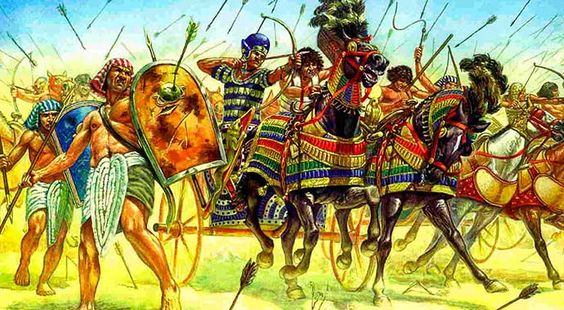

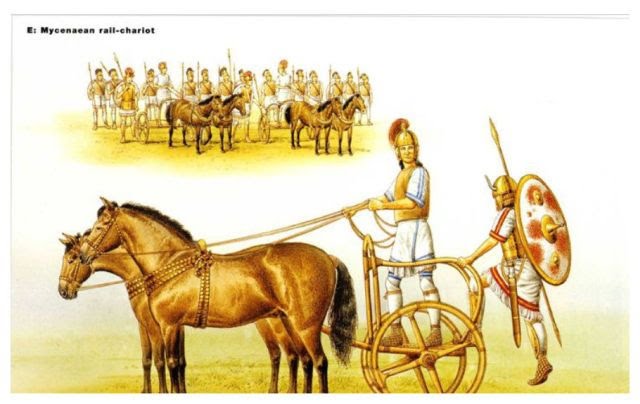

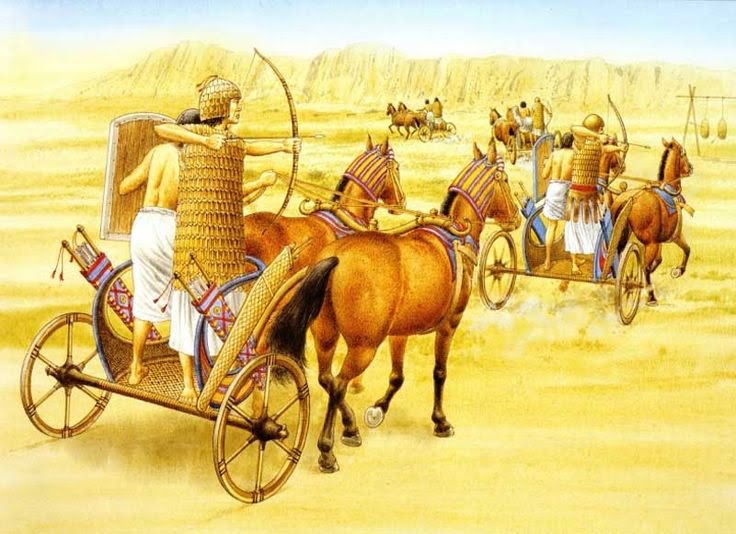

Anyway, back to chariots: the style and manufacture of these 'war-cars' varied across the Bronze Age world (largely the European/Asian 'Near East'), and required mastery in mettalurgy, woodworking, tanning, leatherwork and horse breeding. Let's have a look at a few of the main variations... Chariots of the Aegean RegionIn the lands around the Aegean, the 'box' chariot came into use in the 16th c BC and remained the car of choice for a long time. The cabin was a solid frame of hardwood, shielded side and front with wickerwork screens or hide, supported by a four-spoked set of elm wheels and axle set near the rear of the cabin. By the time of the Trojan war (probably sometime in the 13th c BC), this had given way to the much lighter and faster 'rail' style chariot - essentially just the hardwood frame with no accoutrements or shielding. The crews of driver and warrior would be heavily armoured in grand style, with boar-tusk helms, bronze banded 'lobster' cuirasses and greaves and equipped with shields, spears and broad slashing swords. Homer's Iliad describes the Greek heroes using their chariots mainly as 'battle taxis' to drive to one part of the battlefield, hop off and fight on foot. This is almost certainly a misconception that arose when the Iliad was first written down many centuries after the Bronze Age had ended and chariot warfare was long gone. Chariots of the Anatolian RegionThe sweeping hills and plains of central Turkey were perfect archer and chariot country. Here, the Hittite Empire held sway, and no small part of their dominance over such a huge terrain was thanks to their elite chariot core. Excavated Hittite tablets demonstrate that the chariot was primarily used as something of a shock weapon, actively engaging with enemy chariots in motion, and ploughing into enemy infantry formations. Up until the early 13th c BC, the Hittite chariot core was constructed in a similar manner to the Aegean 'box' style, with a hardwood frame of elm, yew or cypress, all sheathed in hide, but with six-spoked wheels encased in leather 'tyres' secured by copper hobnails (good for grip). Paired crews of driver and warrior were initially the Hittite norm. The driver would be minimally-armoured, sporting perhaps a textile cuirass and a hardened leather belt to support his back. He would probably be weaponless. In contrast, the warrior would be heavily armoured and armed, draped in bronze scale and bedecked with bow, spear, sword and axe. The Nile RegionBut the masters of the chariot in this age were surely the Egyptians. The invading Hyksos had several generations before brought chariot technology to the Nile lands. The Egyptians ousted the Hyksos but held onto the technology, and seized a stock of good horses from their enemies in subsequent wars. Soon, they had perfected the craft of chariot manufacture and Pharaoh's great war factories could produce fleet after fleet of light, nimble and super-fast battle-cars. Indeed, Egyptian chariots were all about speed rather than shock, and they employed an expert archer on every vehicle: in battle they would move like a murmuration of starlings, each paired crew of archer and driver whizzing close to their opponents, loosing arrows while being careful not to become embroiled with enemy infantry or chariotry. In great number, this must have been hugely frightening and demoralising for an enemy infantry host - something akin to what Crassus' Roman legions must have experienced many centuries later when they were destroyed by Parthian archers at Carrhae. Steam-bent ash or elm formed the skeleton of an Egyptian chariot. Ash and Elm were not readily available in Egypt, and so Pharaoh required regular imports of these hardwoods to keep his chariot factories in production. Once a chariot skeleton was ready, ox-hide was stretched over the front to provide protection without adding significant weight (the back and sides were left open to further reduce weight). The D-shaped floor would have been crafted with a mesh of rawhide, providing something of a suspension effect for the crew - no doubt welcome when they charged across a rocky plain! An ash axle, 6-spoked plum wood wheels with rawhide tyres, an elm draught pole and a willow yoke would be added to complete the picture. In all, an Egyptian war chariot would have weighed no more than 30Kg - quite a feat, and just a little more than the weight of three modern road bikes. Recent archaeological finds show these vehicles would have been painted in vibrant colours - one find being a dragoon green cabin edged in blood red. Regarding the crew: the driver was known as a 'kedjen', and he bore a shield as well as the reins. The warrior was called a 'seneny', and he would have carried a composite bow, several quivers, spears, a khopesh (curved sword) and a mace or battle axe. He would also have been clad in a bronze or leather scale corselet and bronze helm. Sometimes, each chariot had a support 'runner', whose job was to sprint alongside or close behind the chariot in battle and finish off enemies wounded by the crew. In the Battle of Kadesh, Pharaoh Ramesses employed Sherden mercenaries to run along with his royal chariots, and tasked them with hacking off the hands of the Hittite dead and dying as some kind of 'kill total'. A Lesson Well-LearnedAt some point near the turn of the 14th c BC -> 13th c BC, the Hittites clearly recognised Egypt's chariot supremacy. This must have been a hard thing to accept as the two were the greatest powers of the time and drawing closer and closer to all-out war. They may well have come to this realisation when, around 1293 BC, Pharaoh Seti routed a Hittite army (mainly composed of vassals) somewhere in Syria. in Dawn of War, I go with this theory, portraying Prince Hattu and his band of soldiers and chariots being torn to pieces by the far faster and nimbler Egyptian vehicles. Regardless of how and when the Hittites were drawn to the conclusion that their own chariotry was not up to the standard of Pharaoh's, we know that they did not sulk about it. Instead they used it as a catalyst to innovate. To reinvent their chariot corps would have required the greatest minds of the Hittite realm. And in terms of the art of chariotry, there was none sharper that Kikkuli. Kikkuli was a Hurrian who served in the Hititte court during the period in question. His name might well be Indo-European for 'Colt', hence my use of the name 'Colta' in Empires of Bronze. Kikkuli ran a chariot academy outside the Hittite capital, Hattusa. This complex encompassed stables, corrals, barracks and an oval exercise field as well as homes for scribes, stable-boys, handlers, grooms and wranglers. Hurrians were famed for their chariot warfare and horse-breeding, and we know from the surviving 'Kikkuli Text' that this man left no stone unturned in his work. He specifies practices such as:

He also masterminded, or at least had a big hand in, the redesign of the Hittite chariot. This new model dispensed with the futile attempts to produce fast and nimble vehicles. What was the point? The Egyptians were miles ahead in these respects. Instead, the new-look Hittite chariot would fully embrace the aspect of shock warfare. Out with the old and artificial rule that a chariot had to be crewed by a pair: now a crew would consist of three - a driver, a warrior and a shield-bearer. This meant a wider base to accommodate the extra man and maintain stability. And they dispensed with light frames and thin ox-hide sheathes - now they built cabins of sturdy timber slats offering excellent protection for the three inside. They crafted wheels from multiple strips of steam-bent wood instead of one - meaning larger diameters and thus bigger wheels. These new chariot cabins must have looked like tanks compared to the old-style vehicles. But surely the poor horse teams would suffer for this: three men to haul around instead of two, as well as a heavier cabin? Well Kikkuli and his team foresaw this and mitigated that risk in their design - moving the axle from its traditional position at the rear of the cabin (meaning the horses bear most of the weight), to the centre. More, we know from the Kikkuli Text that the Hittite Chariot Master was engaged in a special program of horse breeding and diet. He pioneered the technique of feeding his herds not with grass, but with a mixture of barley, wheat, meal, groats and salt. This, along with his selective breeding, is likely to have resulted in gradually larger and stronger horses, capable of hauling these new vehicles and donning bronze aprons and masks for their own protection. These vehicles must have been lumbering as they set off from a standstill, but capable of building up great speed and momentum. The penalty would have come in the shape of manoeuvrability, however - the great weight and momentum meaning that the turning circle would have been huge, unless the driver slowed the vehicle right down first. But every weapon has a weakness, and the key is to make the most of its strengths. For the Hittite King, unleashing this new wing of heavy battle-cars would have been like throwing a single volley of spears - absolutely deadly if aimed well... but if you missed on that one and only throw, anything could happen. In Thunder at Kadesh, I describe these heavy chariots as 'Destroyers', with Prince Hattu leading one vehicle nicknamed 'The Harrower'. Quite apt, given what was to come in their first full-scale outing... The Charge of the DestroyersIn 1274 BC, after years of threats and posturing, the mighty armies of the Hittites and the Egyptians met at last in the Battle of Kadesh. When Prince Hattu led a charge of this new and massive Destroyer wing - numbering anything up to three thousand vehicles - it was devastating, blowing apart Pharaoh's Army of Ra, then making ruin of his Amun camp. The ghosts of past defeats had well and truly been exorcised... but of course that was just the beginning of that long and brutal clash... Thanks for Reading!And remember, you can escape to the Bronze Age and ride a Hittite 'Destroyer' in Empires of Bronze: Thunder at Kadesh - out now!:

|

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed