|

The Trojan Horse is iconic and legendary, yet it is not mentioned even once in Homer's Iliad. In fact, in the entire eight texts of the Epic Cycle , it is only mentioned once and in passing in Odyssey, which tortures us with just a single line: “A single horse captured Troy... We have no firm idea what this ‘horse’ actually was. The traditional narrative is probably most well known, and the sequence of events is:

However, the notion of men hiding within the horse first appears only in the Roman age with Virgil's Aeneid. It does seem like a poetic invention. There are many more theories, wide and varied:

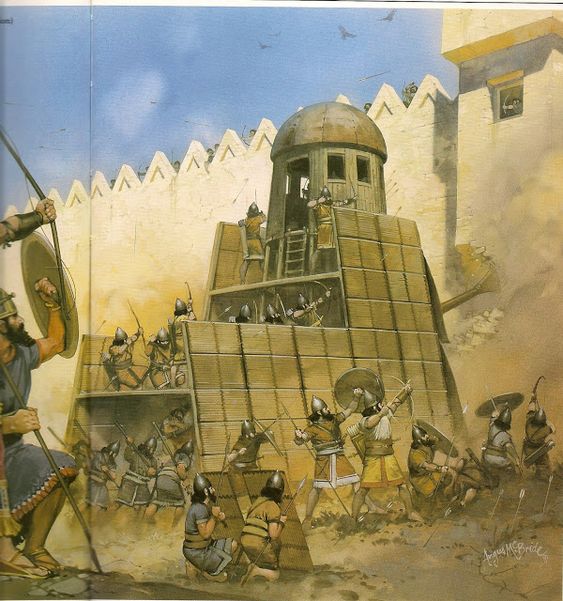

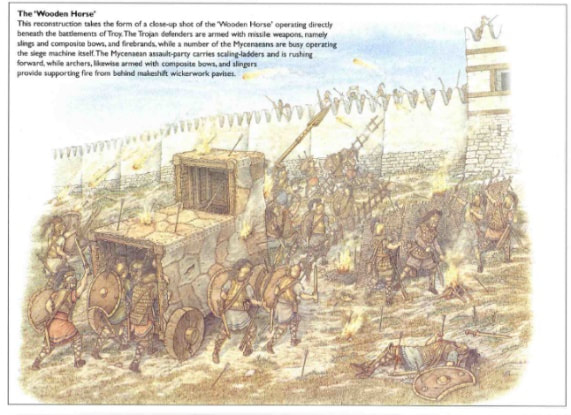

There are even other theories, and the one makes most sense to me as a historian is that the horse was a siege device. Later writers Pausanius and Pliny the Elder were both convinced that this was the case, the former stating: “Anyone who doesn't think the Trojans utterly stupid will have realized that the horse as really an engineer's device for breaking down the walls. Siege technology in this age was advanced. Some devices were often named after animals – The Assyrian Horse, the Wild Ass, The Wooden One-Horned Animal. Assyrian tablets depict the first of these as a ram shed with a ‘neck and head’, the head containing a drillbit used to pick apart walls. One can see in it the visual resemblance with a horse. The siege engine theory is just one of many that I write of in my latest novel The Shadow of Troy!

What are your thoughts and theories? Please do leave your ideas in the comments section, below :)

2 Comments

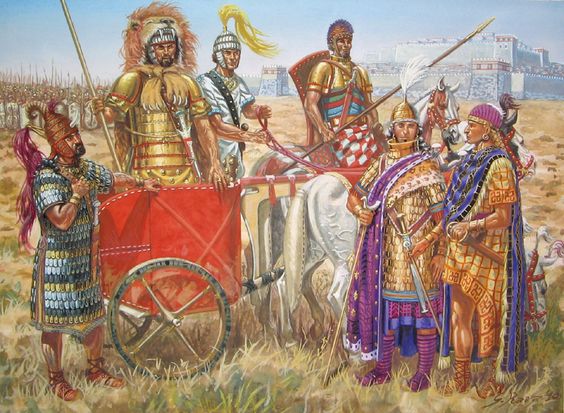

So I returned to the Watling Lodge stretch of the Antontine Wall at the weekend. The place is something of a sanctuary for me - a green, wooden vale that feels like it is in the middle of nowhere (when in fact it is in the heart of the Falkirk suburbs). I particularly like the LiDar imagery (assuming that is what it is) on the new plaques, showing the topography of the wall region. This technology promises to revolutionise archaeology! And here's my video from a few years ago touring the Watling Lodge area. Offer still stands of a free copy of the short story I wrote about the place :) The Trojan War. Everyone knows at least the kernel of the story: Prince Paris of Troy abducted Helen, Queen of Sparta. Incensed, the Greeks gathered a giant army, landed at Troy and besieged the city for 10 years. You might know of the legendary characters: Hektor, Achilles, Priam, Odysseus. Or the factions - the Amazons, the Myrmidons, the Elamites and many, many more. But there is one almighty whopper of a 'faction' that is not mentioned at all in Homer's Iliad. The Hittite Empire - not just an ally of Troy, but her behemoth overlord. You see, the Trojans, plus many of her allies, were for centuries in the Late Bronze Age, merely vassal kingdoms, serving the Hittite Emperor. The near east map of the Late Bronze Age, below, puts some perspective on this. Note: 'Ahhiyawa' was the Hittite name for Homer's Greeks/Achaeans. So where were the Hittites in Troy's hour of desperate need? Homer's Iliad does not even contain a passing reference to them. This is akin to Latvia and Estonia going to war and nobody ever mentioning Russia. However, The Iliad covers just a few months in the 10th and final year of the Trojan War, ending with Hektor's funeral. The things that happened between then and the actual end of the war – the coming of the Amazons and the Elamites, the deaths of Paris and Achilles, the horse, the sacking of the city et al – survive only in the tantalising fragments of the other ancient texts that make up what is known as The Epic Cycle. Regardless, as fragmentary as those texts may be, none of them mention the Hittites either! What’s going on there? One theory is that the Hittite Empire had collapsed by the time of the Trojan War. However, we know that the Greek world collapsed before or at roughly the same time as the Hittite world, so if the Hittites were gone, then so too must be the Greeks, and how could there be a Trojan War then? And even if the end of the Hittite Empire preceded the fall of Homeric Greece by several years, one would expect there to be at least an echo of the Hittites in The Iliad - successor or splinter empires, that kind of thing Most likely, I think, we are looking too hard and too literally at The Epic Cycle texts for a mention of the Hittites. After all, the name ‘Hittite’ didn’t actually exist in the Late Bronze Age. The Hittite people actually referred to themselves as ‘The People of the Land of Hatti’. More, Egypt knew them as ‘The Khetti’. And that’s where one theory arises: Odyssey, the tale of the Greek hero Odysseus’ tumultuous and circuitous voyage home, contains a passage of exposition about the war which mentions the arrival at Troy of a small force known as ‘The Keteioi’ who came to help the defenders.. In the final year of the war, following the death of Hektor, these 'Keteioi' turned up and became one of Troy’s last hopes. Could these Keteioi be the Hittites? It is a frustratingly flimsy deduction but intriguing nonetheless. Certainly, it seems more plausible at least than other wilder theories – that the Amazons were in fact the Hittites (owing to the Hittites' long, dark ‘feminine’ hair and shaved chins), or that a minor Trojan ally, the Halizones, were the Hittites. “Now as we have come to an agreement on Wilusa over which we went to war.” Onomastic similarities (similar-sounding names) aside, there is another compelling piece of evidence that the Hittites could have been at the Trojan War in some capacity. It stems from an excavated Hittite tablet known as the 'The Tawagalawa Letter', named after the brother of the Greek King to whom it was addressed. This tablet is dated to the reign of the Hittite King Hattusilis III (1267-1237 BC), and mentions a conflict over Troy between The Greeks and the Hittite Empire, roughly dating to 1260 BC. Could the 'Keteioi' of Odyssey and this 'Tawagalawa Letter' conflict be evidence that the Hittites took part in the legendary war? Perhaps. It is certainly not concrete evidence, but definitely intriguing. Now, if we work on the assumption that they were at the war, we must then ask why they made so little impact. The Hittite Empire was - only a generation earlier in 1274 BC - the greatest military power in the world, having just turned the mighty Pharaoh Ramesses and his Egyptian armies away from Kadesh in another of the Bronze Age's famous clashes. Surely the Hittite armies should have turned up at Troy and been able to steamroller the Greeks? To understand why this apparrently didn't happen, we must look a little closer into the goings-on in the Hittite Empire during the short gap between the wars at Kadesh and Troy... Around the time of the Trojan War, King Hattusilis III had only recently claimed the Hittite throne from his nephew, Urhi-Teshub. He decided to exile rather than kill the previous incumbent, though he must quickly have realised that this was a huge mistake. Many of the vassal kingdoms, sensing that the exile might be on the brink of returning in an effort to reclaim the throne – bringing war and retribution with him – wavered in their loyalty to King Hattusilis’ rule. Hattusilis was also plagued by jibes of illegitimacy from mocking foreign rulers. The Great King of Assyria – a rival empire – sent neither envoys nor gifts to Hattusilis coronation ceremony, and went as far as to label him as ‘A substitute for the real Hittite King’.

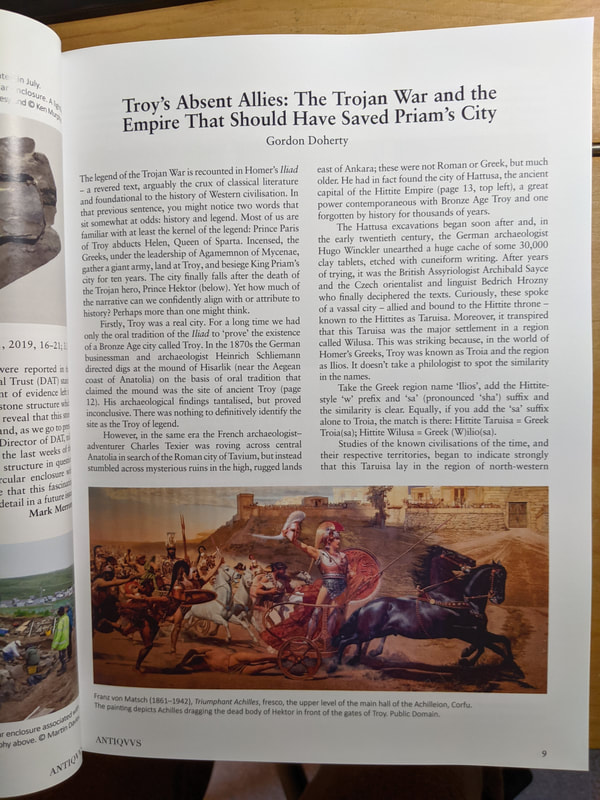

Sensing trouble, Hattusilis sought new allies. The greatest agreement of this kind was that which he struck with Ramesses II of Egypt. He and his erstwhile sparring partner from Kadesh agreed what is known as ‘The Eternal Treaty’ or ‘The Silver Treaty’, which laid out the conditions of a defensive alliance between the Hittites and the Egyptians. This effectively mitigated the huge threat posed by Assyria, and plausibly would have freed Hattusilis and his Hittites up to tend to the long unanswered call for help from Troy. Yet any force he might have taken to Troy would have been likely been severely depleted from the recent war to oust his nephew. This could tally with the attested small contingent that the Keteioi brought to the Trojan War. The Odyssey does not describe what the Keteioi went on to do upon their arrival. So I have taken up the challenge to tell the story on the premise that they were, in fact the Hittites. The Shadow of Troy tells the tale of the epic climax to the greatest war of all time. Quickie blog this time - just wanted to shout out about an article I wrote about the historical background to The Shadow of Troy, in the autumn '21 edition of Antiquus magazine.

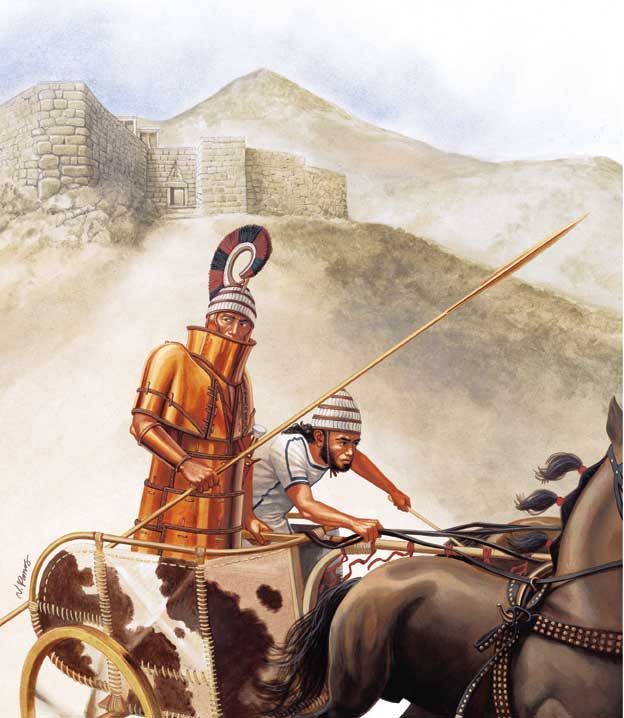

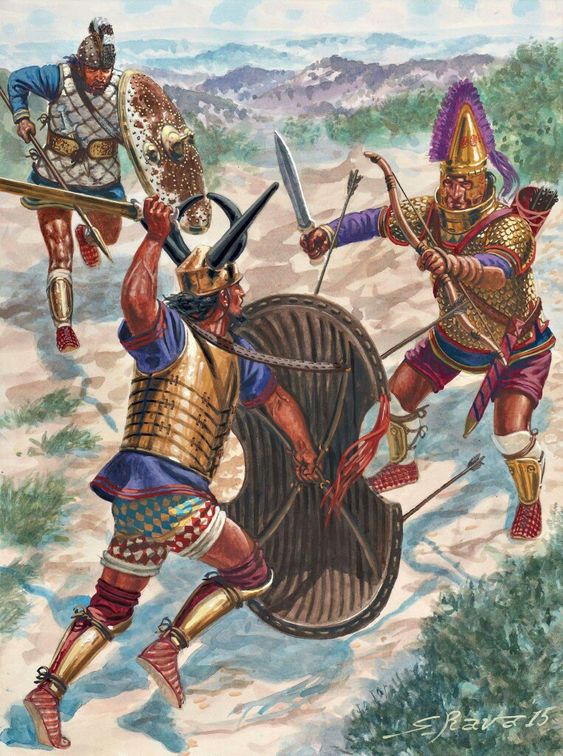

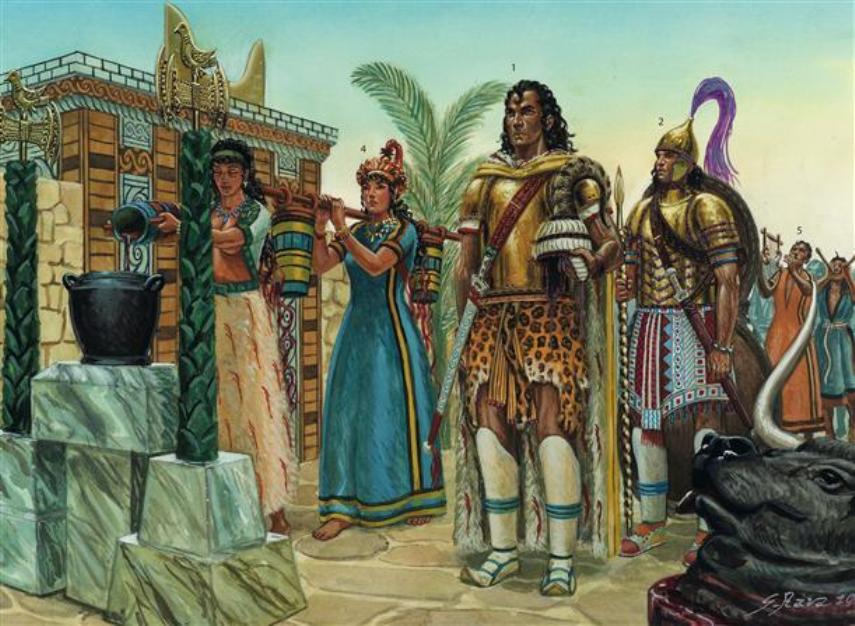

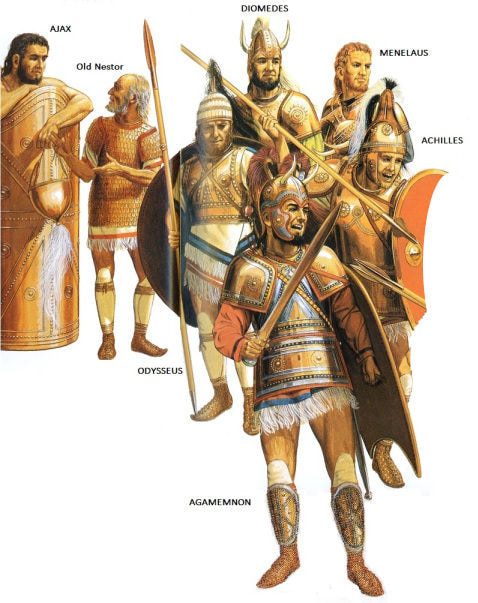

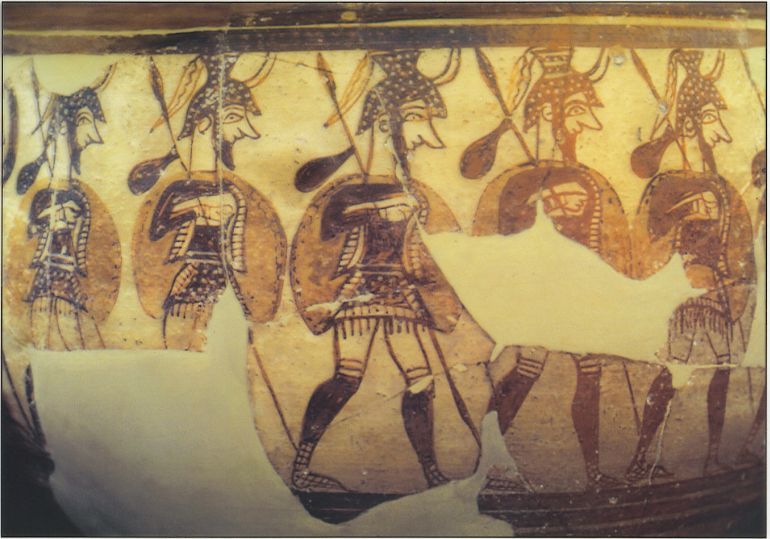

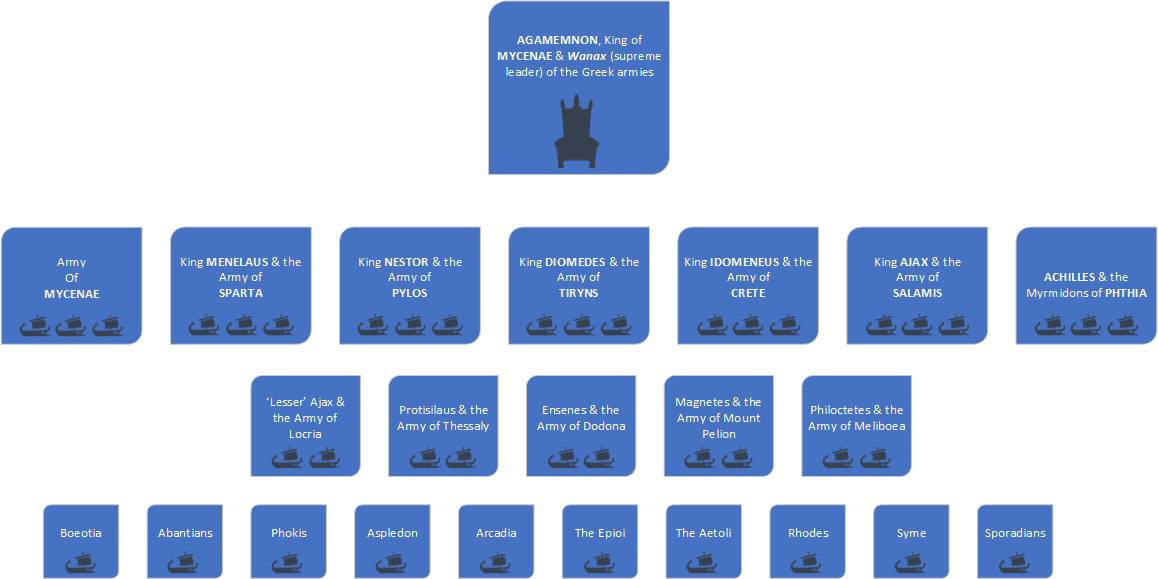

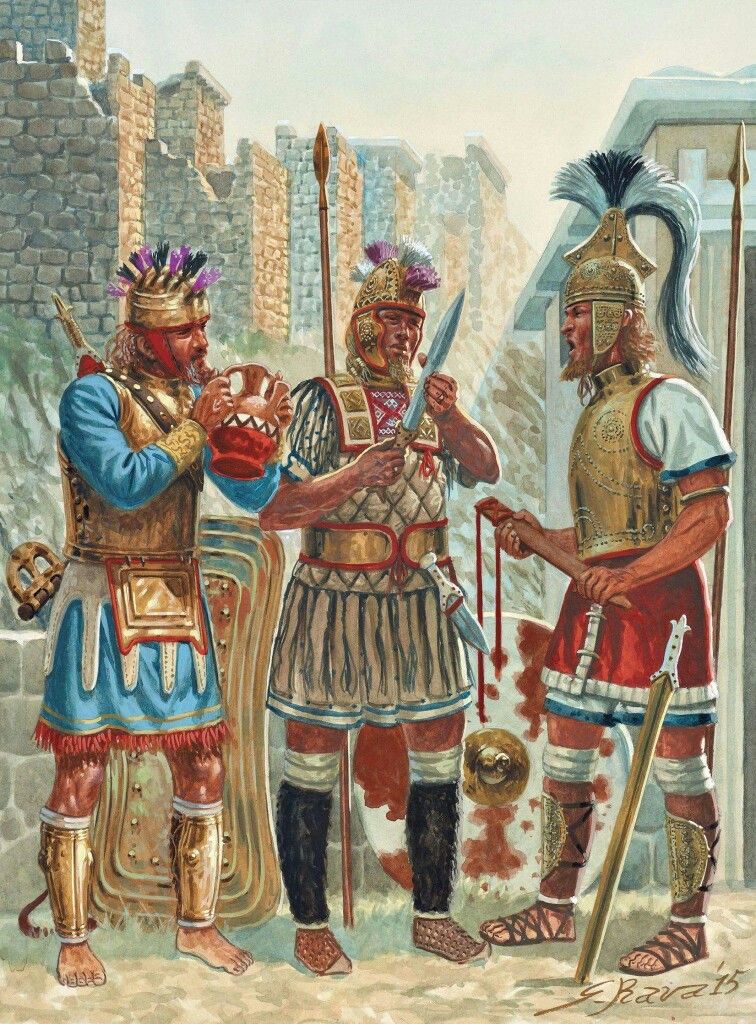

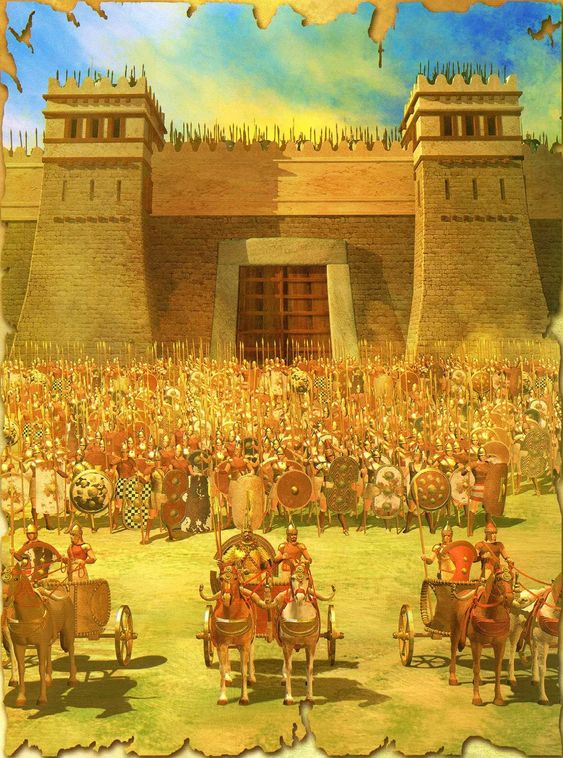

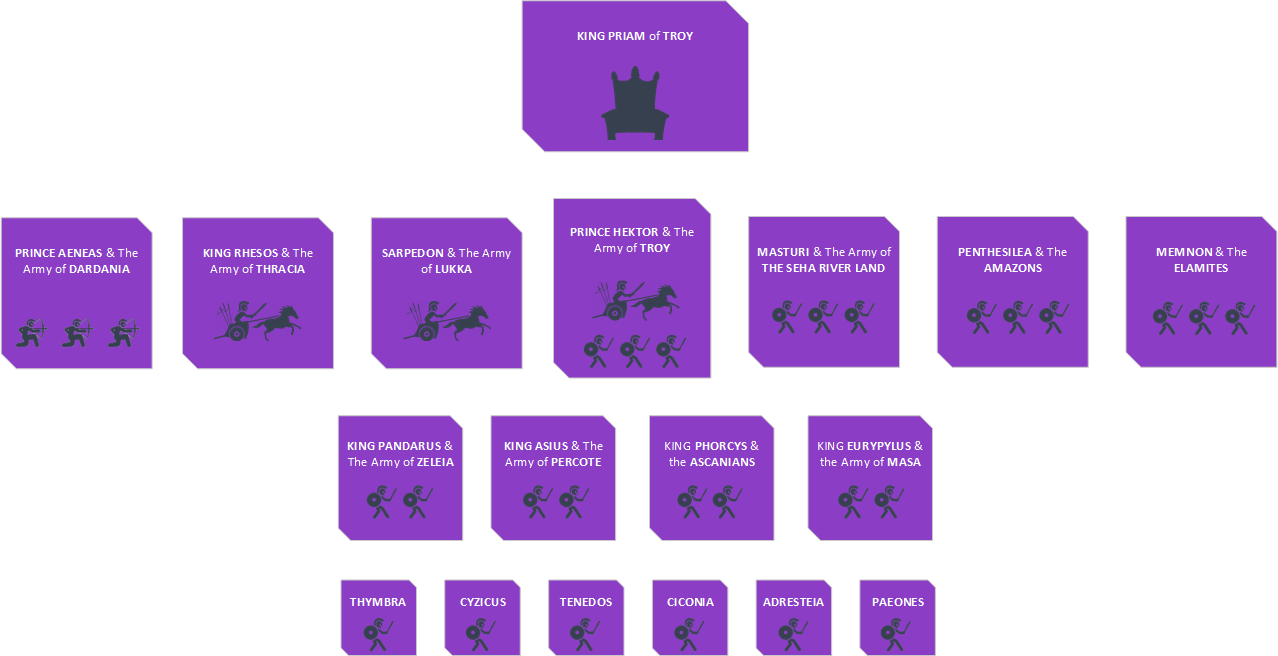

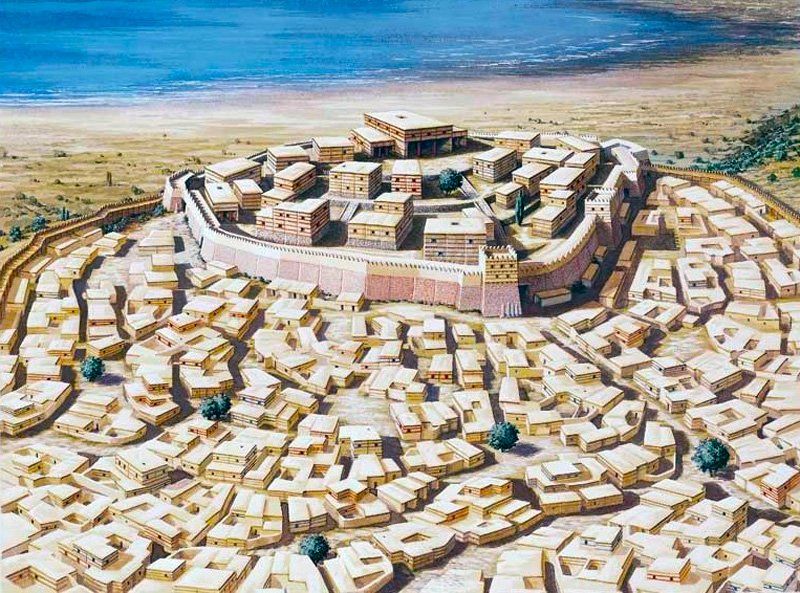

Nice to see my ramblings in glossy format! Also, it was great to work with the team there, and to discover all the other historical content they cover. The legend of the Trojan War has held the attentions of countless generations - from those who lived in its aftermath right through to the present day. Why the eternal fascination? Personally, I have never been able to leave alone the thought of what might have been had Hektor beaten Achilles. Could it have tilted the balance of the war in Troy's favour? Then again, if it had played out like that, perhaps the epic tale might never have been born. Troy had to fall in order to become the legend that it is. Had King Priam's army and those of his allies staved off the Greeks and sent them scuttling back to their homeland*, would that tale of a failed siege have been as worthy of lore? Maybe, but it would have a very different spin on it and would be composed by a Trojan bard no doubt**. *There are theorists out there who speculate this might actually have happened, and that the tale of Greek victory is a huge piece of fabrication. **Tantalizingly, Calvert Watkins of Harvard University suggested that some as-yet untranslated Hittite texts might contain the remnants of what he called a possible "Wilusiad". This would have been, he hypothesized, another historical epic about the Trojan War but one written from the perspective of the Trojans or the Hittites rather than the Greeks. Imagine! Thinking on this for the thousandth time put me in the mood to have a look at the attested forces who waged the war. For it was they, not just Hektor and Achilles, who fought out this conflict. What follows is an attempt to put a plausible shape and size to the two forces who battled over the city some 3,200 years ago. The Greek ForcesThe armies of the Greeks ('Ahhiyawans' to the Hittites or 'Achaeans' in Homeric parlance) were led by Agamemnon, the warrior king of Mycenae. Greece of this era was not in any way a nation. Instead, the rocky peninsulas and archipelagoes housed a number of small but powerful city-states, each of whom considered themselves proudly independent. So it was no mean feat when Agamemnon managed to bind them together into a unified force for the assault on Troy. Legend has it that he achieved this by citing the Oath of Tyndareus - when Queen Helen of Sparta chose to marry Menelaus, all of her rejected suitors swore to protect the marriage, so when she absconded with Prince Paris of Troy, they were obliged to unite and act. But in reality, without such a glittering prize as Troy, it is highly unlikely that the joining of the many city-states could have occurred or held for as long as it did (the Trojan War supposedly lasted some ten years). Agamemnon's forces gathered at the port of Aulis for the expedition to Troy. What kind of army would this have been? Given the largely mountainous terrain in Greece, their style of warfare is likely to have been something akin to that of sea raiders. Thus, the gathered forces are likely to have been largely composed of spear and sword infantry with a small number of elite royal chariots. Homer's Iliad has a very famous scene in it known as 'The Catalogue of Ships' in which he slavishly details every single faction involved in the Greek effort. We also hear of the Greeks attacking Troy with 'one thousand black boats'. Given a warship of the age might cary 30-50 men, this would equate to an army of up to 50,000. Quite simply this is highly unlikely. A force of a few thousand, maybe up to 10,000, is more plausible and for that age and region, still represents a colossal military expedition. There were some major and many minor factions involved. The following graphic (click to enlarge) aims to put some kind of proportional shape to the expedition force. The Armies of Troy and her AlliesPriam was the King of Troy, but the most powerful man in the city was most likely his son and heir, Hektor. Hektor was in his prime, something of a battle-hero and talisman to the Trojan forces and citizens. He, along with his most senior princely brothers Paris, Deiphobus and Scamandrios, would have led the native Trojan army. This would have been a small but elite force, composed of infantry spearmen, archers and a crack wing of war-chariots (such as those who aided the Hittites at The Battle of Kadesh). The bowmen and chariots in particular would have distinguished the Trojan forces from the Greeks: Anatolia (unlike the Greek mainland) sports many flat and sweeping plains - perfect country for the chariot, and a land with a millennia-old archery tradition. As soon as they got wind of the Greek invasion, Priam and Hektor sent a call for help to their allies, a call that stretched far and wide. Friendly states all along the western Anatolian coastal regions arrived, so too did further flung allies - from across the Hellespont and even as far away as Elam (roughly modern Iran). An outline of the known allies is depicted in the graphic below (click to enlarge). The Trojans were most likely outnumbered by the Greeks, but with Troy's walls and highly-defensible position on a coastal mound, they had more than enough soldiery to frustrate the besiegers - indeed, that is probably why the Greeks were forced to employ trickery in the form of the Trojan Horse to finally take the city. One outstanding question remains, however: Just look at the 'world' map of the time (below) - Troy was but one vassal city on the edge of the huge Hittite Empire. And the Trojans had only a generation earlier supported the Hittite army at the Battle of Kadesh, so surely it was time for the Hittites to repay the favour? With the Hittite emperor and his armies - probably the most feared force in the world at the time - Troy need not have been outnumbered. So where were the Hittites, the mighty overlords and supposed protectors of Troy? It just so happens that that's the topic of my next blog - read it here :) Thanks for reading! If you like the history, you might be interested in my fictional take on the war - Hittites included! THE SHADOW OF TROY is available at all good online stores.

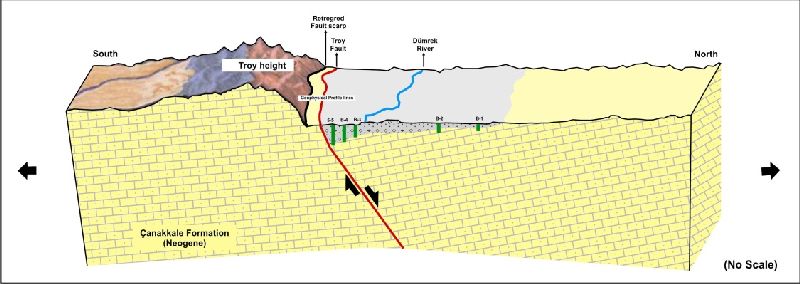

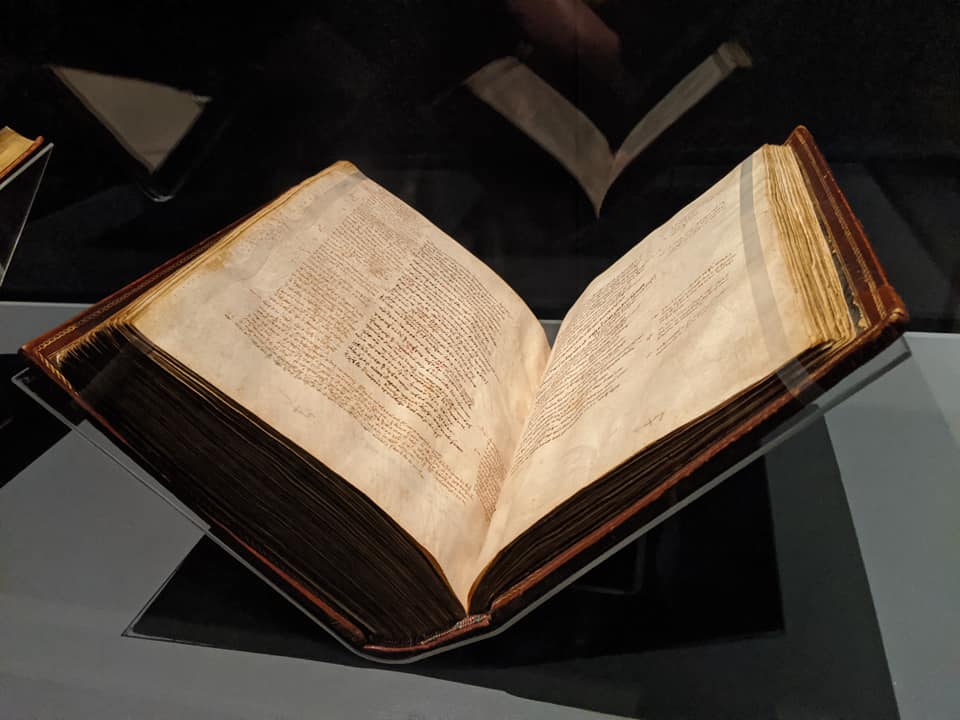

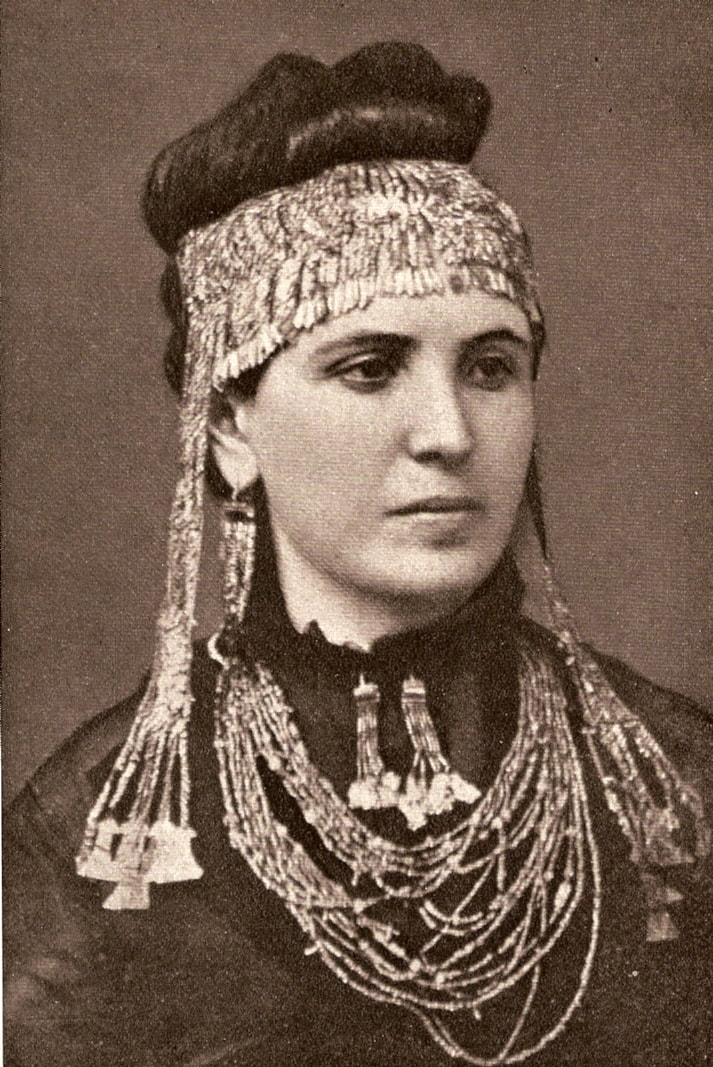

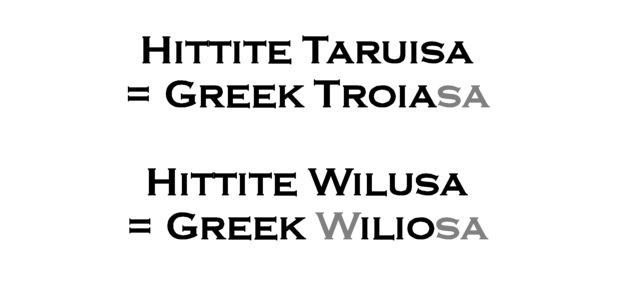

The legend of the Trojan War is recounted in Homer’s Iliad – a revered text, arguably the crux of classical literature and foundational to the history of Western civilization. In that previous sentence, you might notice two words that sit somewhat at odds: history and legend. Most of us are familiar with at least the kernel of the legend: Prince Paris of Troy abducts Helen, Queen of Sparta. Incensed, the Greeks under the leadership of Agamemnon of Mycenae, gather a giant army, land at Troy and besiege King Priam’s city for ten years. After the death of the Trojan hero, Prince Hektor, the city finally falls thanks to the trickery of Odysseus and his Trojan Horse. Yet how much of the narrative can we confidently align with or attribute to history? Perhaps more than you might think... Firstly, Troy was a very real city. For a long time we had only the oral tradition of the Iliad to ‘prove’ the existence of a Bronze Age city called Troy. In the 19th century, Heinrich Schliemann directed digs at the mound of Hisarlik (near the Aegean coast of northwestern Anatolia) to investigate the theory that the mound was the site of ancient Troy. His archaeological findings tantalised, but proved inconclusive. There was nothing to definitively identify the site as the Troy of legend. However, in the same era, the French archaeologist-adventurer Charles Texier was roving across central Anatolia in search of the Roman city of Tavium. In fact, he instead stumbled across mysterious ruins in the high, rugged lands east of Ankara – ruins that were not Roman or Greek... but much, much older. He had found the city of Hattusa, the ancient capital of the Hittite Empire – a great power contemporaneous with Bronze Age Troy and one forgotten by history for thousands of years. The Hattusa excavations began soon after, and in the early 20th century, the historian-archaeologist Hugo Winckler unearthed a huge cache of some 30,000 clay tablets, etched with cuneiform writing. After years of trying, it was Archibald Sayce and Bedrich Hrozny who finally deciphered these Hittite texts. Lo and behold, these spoke of a vassal city – allied and bound to the Hittite throne – known to the Hittites as Taruisa. More, it transpired that this Taruisa was the major settlement in a region called Wilusa. This was striking because, in the world of Homer’s Greeks, Troy was known as Troia, and the region as Ilios. It doesn’t take a philologist to spot the similarity in the names. Take the Greek region name ‘Ilios’, add the Hittite-style ‘w’ prefix and ‘sa’ (pronounced 'sha') suffix and the similarity is clear. Equally, if you add the ‘sa’ suffix alone to Troia, the match is there. Even better, further studies of the Hittite tablets began to indicate strongly that this Taruisa lay smack bang in the region of northwestern Turkey where Schliemann had been digging. In other words we had our first historical attestation of Troy. Secondly, there was a war over Troy in the Late Bronze Age.

Thirdly, the Trojan War might well have happened around 1260 BC. While the war has been ‘dated’ to various decades around the end of the Bronze Age, with estimates spanning 1280-1180 BC, I believe that the war from which the legend derives occurred in the earlier part of that range. My rationale is threefold:

Fourthly, Troy was not a 'Greek' style city. Priam's capital has been depicted in countless works of art, film and literature as a golden city of palaces and orchards, and most often Aegean Greek or even anachronistically classical in style & culture. This is understandable given that the The Iliad is told from a Greek perspective, and was rewritten time and again in the much later classical period. Historically, the city of Troy was almost certainly a cosmopolitan hub – a Singapore of the Bronze Age, a crossroads between east, west, north and south. The city’s markets and in particular her trade ports would have been constantly clogged with merchants – from Mycenae, Egypt, Babylon… even tin traders from distant Britain! Underneath this current of passing trade, I believe that the people of Troy were more likely to have been culturally Anatolian than Greek. Why? The practices detailed in The Iliad – such as Hektor’s funeral ritual with first a pyre then the cleaning and burial of his bones, plus his brother Deiphobus’ immediate marriage to the widowed Helen – are very strikingly Anatolian and specifically Hittite customs. Supporting this angle is the one and only writing find from Troy - a seal, marked not with Linear B Greek language, but with Luwian (Hittite) heiroglyphs. The army of Troy was another thing which would have distinguished the Trojans from their attackers. Agamemnon’s forces – from the mountainous regions of Greece – appear to have been largely composed of spear and sword infantry with a small number of elite royal chariots. In contrast, the Trojan military would have been trained on the sweeping plains of Anatolia – perfect country for archery and horse breeding – and would have comprised more of both bowmen and chariots. Walking in Homer's Footsteps It was with the above historical foundation that I set out to write my story of the Trojan War 'The Shadow of Troy' I assumed I'd fly through the story, what with so much drama and detail to draw upon. But it wasn't as easy as I'd hoped! My first draft turned out to be something of a slavish regurgitation of The Iliad. The Gods weren't present, but almost everything else was: every cut to the hand, every turn of weather and all the most famous poetic lines were in there. So… I tore it up and started again. My goal, you see, was never to simply recount the tale that Homer had already told so well. I wanted to get under the skin of the legend, to understand how things might have been in the pauses between the verses of The Iliad... to match up the poetry against the historicity of the excavated tablets and finds. I thus opted to omit and truncate many events and minor characters in order for The Shadow of Troy to be the story I wanted it to be. This allowed me great freedom to write about the grimier, guerrilla-style military necessities which surely must have accompanied the heroic one-on-one duels, to portray more plausibly the likely numbers of troops on each side, and to examine the primal trauma such a brutal war must have caused the individuals involved - the painting ‘Ulysses and the sirens’ by Herbert Draper, captures this theme with haunting perfection.  'Ulysses and the Sirens' by Herbert Draper. In it we see Odysseus on the way home from the Trojan War. He has tied himself to the ship's mast so that he will not be lured into the waves by the Sirens. But all is not as it seems. Just look at the torment wrought across the hero's face, the eyes glazed with madness. Is it really the Sirens who are driving him from his wits... or is it memories of the war just gone, of things seen and deeds done? In 'The Shadow of Troy' I also:

The Shadow of Troy is my take on the Trojan War. Regardless of how you choose to interpret the legendary story – as a poetic symbol or as a historical record – the outcome of the tale is a sorry one: the Trojans lost everything; King Priam’s line was wiped out and his city was never the same again. Worse, the conquering armies soon discovered that their victory was fleeting, for their realm across the sea quickly fell into the dust of history too. One theory is that they were consumed by a storm of change. But that is another story... |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed