|

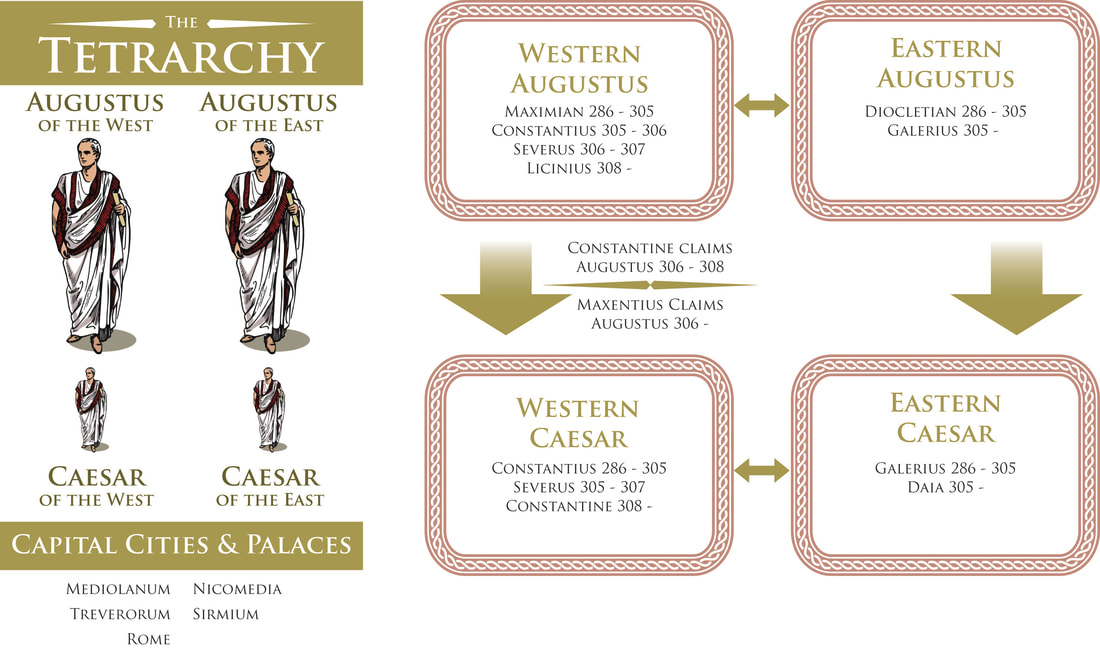

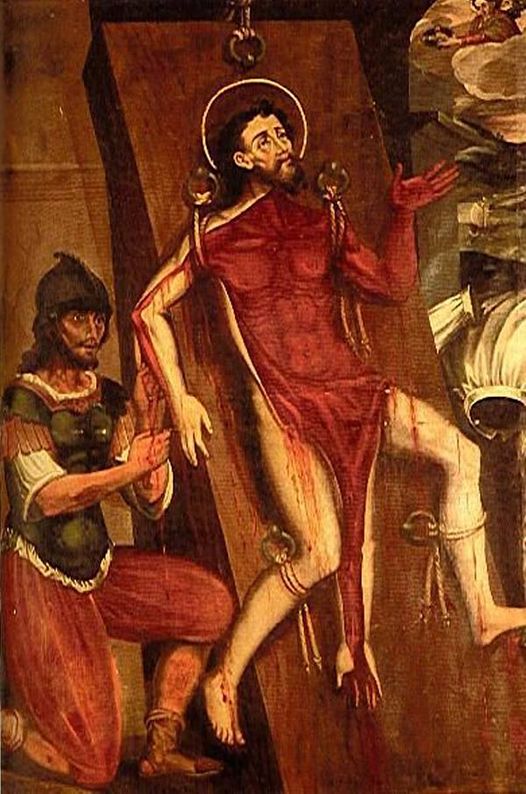

In the late 3rd century, the Roman Empire was a creaking mess. Riven by endless civil wars, succession struggles and splinter empires, the whole realm looked to be on the brink of disintegration. Along came Emperor Diocletian, who proposed a new system of rule: The Tetrarchy. Here, the empire would be split into more manageable Eastern and Western halves, with each half having an Augustus (a senior emperor) and a Caesar (a junior emperor). When an Augustus abdicated or died, his Caesar would step into his throne and appoint a Caesar of his own. And so on and so forth. No more wars of succession! ...yeah, right. Diocletian's vision was well-intended, but dreadfully executed. At the dawn of the 4th century AD he made one of his biggest mistakes by sponsoring the Great Persecution - a tyrannical pogrom of the empire's many Christians, led by himself and his Eastern Caesar, Galerius. Diocletian's complaint against the Christians was this: for centuries, the citizens of the Roman Empire had worshipped the old pantheon of Jupiter and the Olympian family. In doing so, they were also acknowledging and paying homage to the emperor himself, venerating him as the embodiment of one of those Gods. Indeed, Diocletian had a penchant for painting himself gold and insisting on being addressed as Jupiter. Citizens were expected to demonstrate their loyalty to Jupiter and thus to him by sacrificing animals. The Christians, however, did not believe in the sacrifice of any living creature. They also did not believe in worshipping their god 'via' an emperor. In the eyes of Diocletian, they lived their lives in the Roman Empire, but not as part of it. This would not do, and so the Great Persecution began. What came next was an age of public burnings and peelings, of riots and butchery across the empire's cities. It must be noted that much of the descriptive that follows comes from the Christian authors writing after this bleak time, and of course they were undoubtedly biased and keen to stress just what horrors their predecessors had been put through. It all began in a relatively gentle fashion with the legions. Soldiers seen making Christian gestures were blamed for imperial and military failures, and were summarily dismissed, losing their reputations and pensions. Things became bloody when Diocletian and Galerius were at the city of Antioch to witness a ceremony of sacrifice. The proceedings were interrupted by a loud and grating voice. The Deacon Romanus circled the ceremony over and over, denouncing the act. Diocletian ordered his arrest, first sentenced him to death, then changed his mind and ordered his tongue ripped out first. Returning to his Tetrarchic seat at the city of Nicomedia, Diocletian then set about formalising his dislike for the Christians. Egged-on by his underling, Galerius, he then issued what has come to be known as the First Edict of Persecution - a call to destroy all Christian buildings and scriptures and seize the faith's property and wealth. “ Diocletian recommended this should all be carried out without bloodshed. However, in practice - and overseen by Galerius - it was very different. Etius was one of the first to be martyred. Having torn down a copy of the edict in Nicomedia's forum, he was arrested and burnt alive. Burning happened to be Galerius' favoured way of dealing with the Christians. Indeed, one prominent Christian church in Nicomedia was soon after set ablaze while still packed with worshippers. Bishop Anthimos escaped the flames, only to be captured and beheaded. Shortly after this, the imperial palace caught light and the Christians were blamed. This, in a way, legitamised Galerius' brutality and so many more Christians were now hunted down, beaten and, yep, burned alive. In order to weed out hiding Christians, the tests of sacrifice were became mandatory and took place all across the Eastern Empire. After refusing to comply, Diocletian's butler, Peter, was hung by his wrists and had the skin peeled from his body. If that wasn't enough he was then "roasted on a gridiron".

Countless burnings, peelings, beheadings and more followed. These atrocities threw the empire into chaos: widescale riots and protests against the persecutions only led to retaliatory mob attacks on the rioters and further edicts that intensified the brutality. Into this bloody and fiery world, Constantine the Great was born. Sons of Rome tells the story of his rise during the days of the Persecution and of the Tetrarchy, and his days of friendship with Maxentius, son of a Western Augustus. A friendship that was not to last...

0 Comments

The Rise of Emperors trilogy tells the story of the Roman Emperors Constantine the Great and his bitter rival, Maxentius. I'll leave the books to recount the epic tale of their struggle, but in this blog I wanted to look at the life and legacy of the first of those characters - to understand not Constantine the Great, but Constantine the man. His nuances and quirks, his values and beliefs, his weaknesses and strengths. Let's just quickly summarise what history tells us at a glance: Constantine united a crumbling Roman Empire, fighting a legendary battle at the Milvian Bridge along the way - before which he was inspired by a sign from God in the sky, and after which he ended the oppression of the Christians. Right? Well, sort of. That is the distilled version of Constantine that comes down to us from the ancient texts. Many of these were penned by Christian authors writing about him after his wars and even long after his life. They absolutely venerated him. Some talked of him as a saint, the bringer of Christianity, even the Thirteenth Apostle. But these writings do not tell the whole story, for they largely obscured other writers (notably by Zosimus & Eunapius) who cast Constantine as a bit of a monster - politically ambitious, ruthless and manipulative. Such extremes! When reading into any part of history and the associated debate, I always seek some level of plausibility and balance - I like to finish my studying sessions feeling that I have understood the past as it might have been. So the commonly polarised caricatures of Constantine - which remain with us to this day - always leave me feeling dissatisfied, incomplete. So take away the tug-of-war panegyrics and invectives, the grand orations and the legends. How much do we really know about the man? The answer is short: very little. But here are a few scraps of information and anecdotes that may colour in the grey areas and raise an eyebrow or two... Childhood

Adolescence

Rise to Military Prominence

Battle for the Empire and BeyondAs soon as Constantine became emperor in his father's place, the cracks began to appear in the Tetrarchic system. Galerius raged against his accession, and jealousies began to arise elsewhere. His opponents questioned him at every turn: was he a senior Augustus or merely a junior Caesar? Emperor of all the West or just the northern part? Who ruled Italy and Africa? More importantly, who ruled the ancient capital of Rome - currently occupied by Maxentius? Tensions rose and rose and eventually boiled over. What followed was an epic cycle of battles against Maxentius for complete control of the Western Roman Empire - a struggle that changed the course of European and world history. Later years

His legacy

ConclusionConsidering the guiding figures in his life - his mother Helena, his first wife Minervina, his tutor Lactantius - Constantine must have been intimately familiar with Christianity. Perhaps he was spiritually open to it also. Or was he only interested in creating a religious harmony through which he could further his ambitions? As the historian David Potter muses: "Constantine didn’t mind if his subjects were not Christian. More important that they were his subjects." However, particularly because of his telling decision to spurn Galerius' daughter in favour of Minervina - a choice that both forewent personal gain and invited danger - I suspect there was more than naked ambition behind his bond with the religion. Conversely, given his years of warmaking and the blood-curdling rumours of his second wife's demise, it is hard to uphold any view of him as a gentle, tolerant figure. Tens of thousands of men must have died on the ends of his legions' swords. Thus I suspect that - like most people - he found his way to his faith gradually, perhaps guided there by some of the terrible events he witnessed… and some that he created. References

|

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed