|

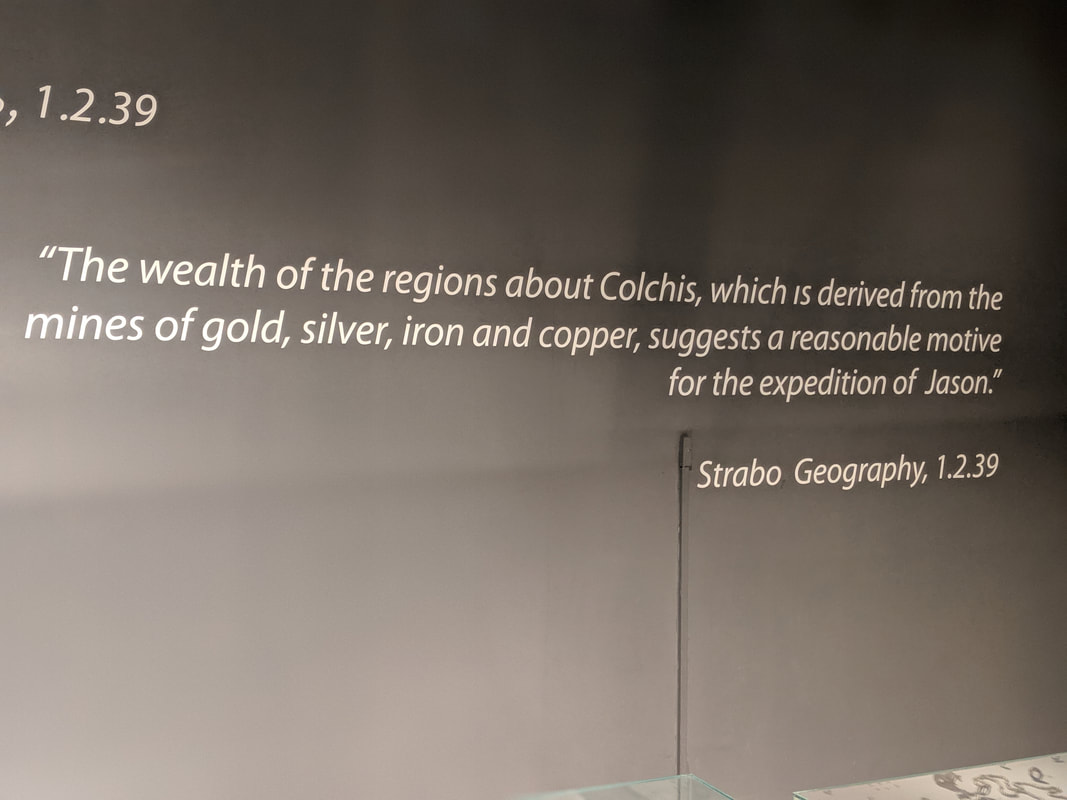

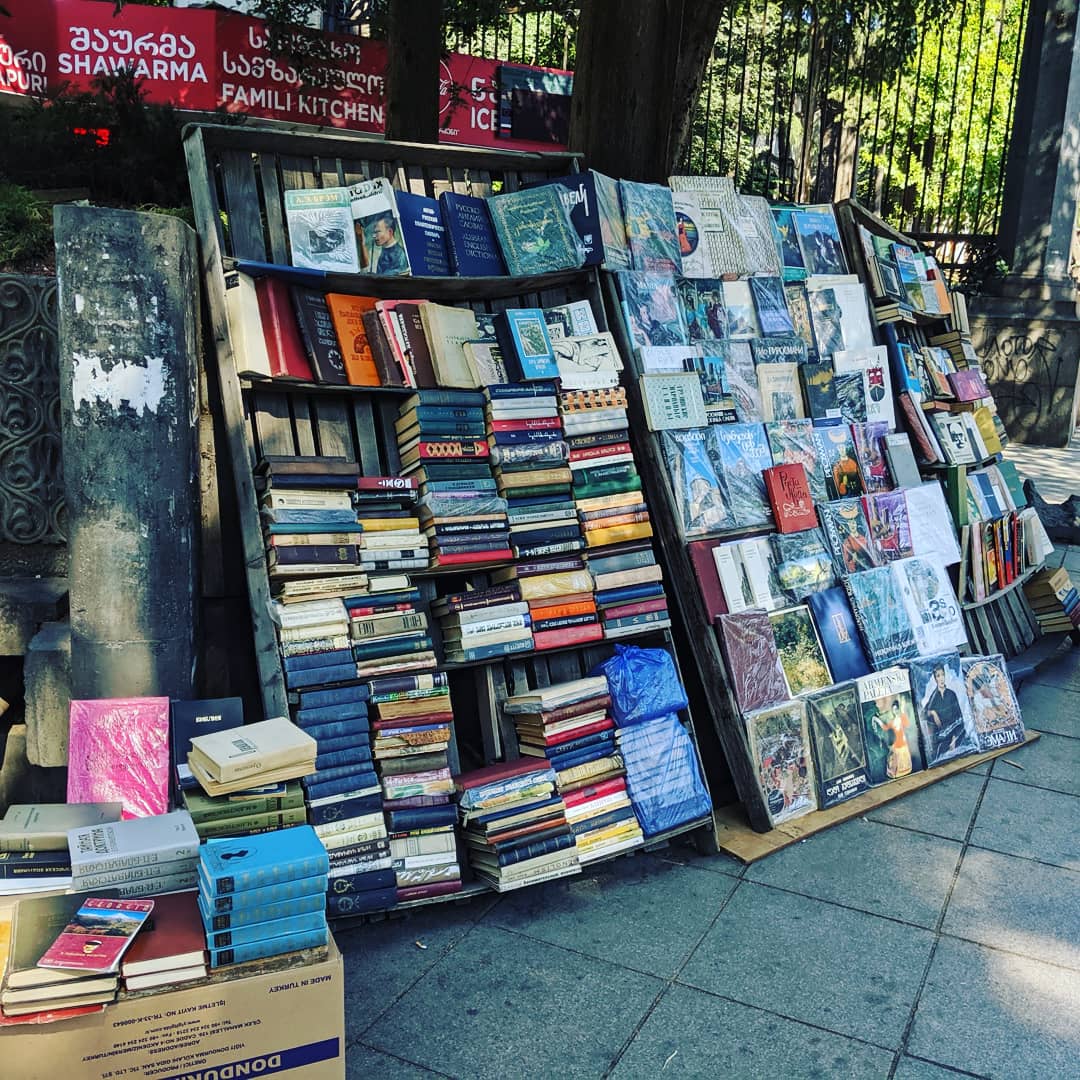

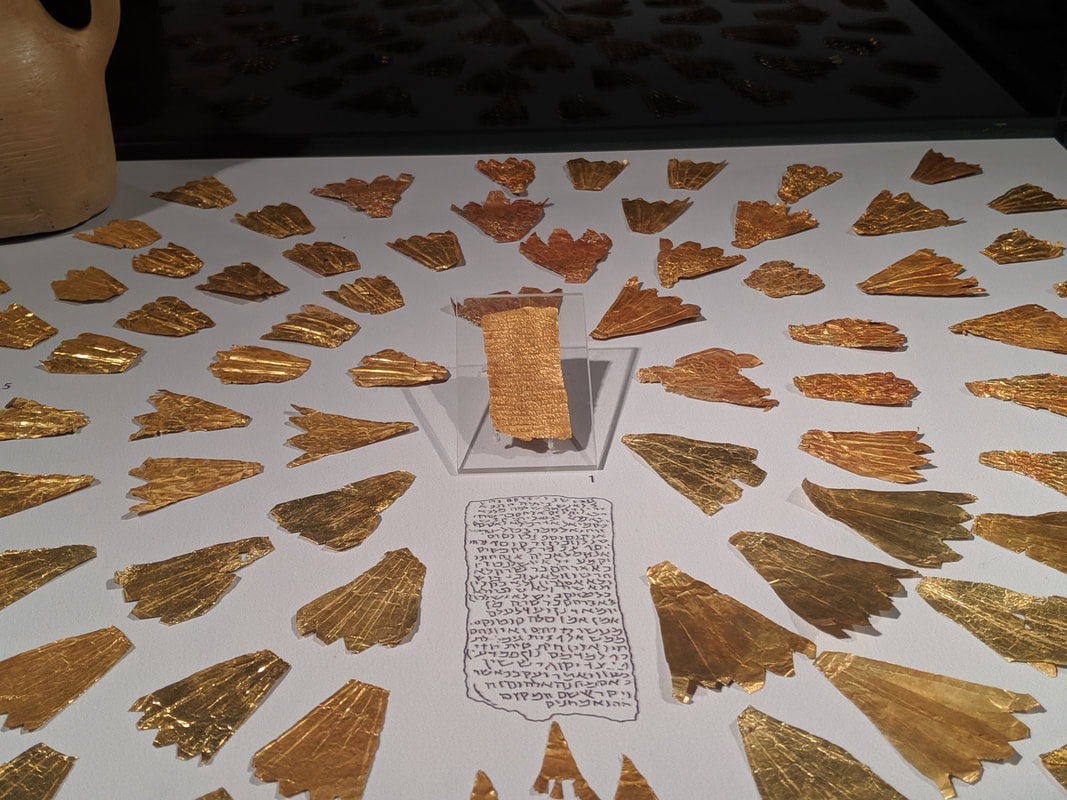

Onto the final leg of my Great Hittite Trail tour. I took a coach from Erzurum's out-of-town bus station, which zig-zagged northwards through the Pontic and then the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, rolling along precipitous mountain roads and giving great views of inland lakes and soaring peaks. I had planned this leg of the journey as best as I could, but the advice online and in books was sketchy, at times contradictory., and faintly worrying! ""You will have to cross the Turkey-Georgia border on foot, and be prepared to haggle with the squadron of taxi and dolmus drivers on the other side. They will take dollars or sterling. You can't get a hold of Georgian Lari until you're inside the country"" I had images of me crawling through a hole in a chickenwire fence then scuttling across a dusty car park, ducking every so often to hide from border guards. In fact, the border crossing was first rate - just like an airport without the planes. I will admit I was a little disappointed after all my imaginings :) A Dolmus into Batumi was an interesting experience. No seatbelts, 100+mph and 'take your life in your hands' overtaking on a single carriageway - yikes! The Georgian countryside was markedly different to that on the Turkish side: on my right rose the verdant, tree-lined Caucasus range whose peaks were shrouded in cloud, and on my left was the coast, sun-washed and sweltering. In many places, it reminded me very much of the carribean landscape, with hillside homes standing proud of the woods here and there, pitched on stilts. Upon entering Batumi and crawling through its traffic, I also noticed a rather unusual fashion amongst the men of the city: standing around on street corners with their t-shirts rolled up from the waist, right up to the armpits! Perhaps it was because Batumi was very hot and muggy. It was also very busy and from what I could detect on the way through, the air seemed to be quite polluted. Fortunate then, that I was not stopping here. Near Batumi's central train station, I hopped off the dolmus and into another taxi which sped me at warp speed along the highway up the Black Sea coast through fresh country air and towards a quiet little place known as Ureki Beach. I had picked this place at random as a good 'downtime' stop for a few days. Ureki Beach sports black, magnetic sand, and the perceived healing qualities of the sand make it a very popular destination for those with health problems, including bone and cardiovascular diseases. I checked into a very pleasant beach shack there and - after weeks of fast-paced travel - began to wind down. But why, I hear you ask, why Georgia? What has it to do with the ancient Hittite Empire? Georgia was, admittedly, a bit of a shot in the dark. I knew from my research that the rough region of the modern country was, 3,000 years ago, on the periphery of the Hittite realm. On the maps of the Hittite world that modern historians and archaeologists have put together, we know only of a people known as the Azzi-Hayasi living somewhere near the Georgia-Turkey border. Any further north than that (i.e. right where I was), and we're into the realm of legend. But legend has it that, during Hittite times, one of the grandest expeditions took place, taking a certain Greek hero to this region. I'll let my video explain (and it also gives a quickfire review of my travel reads): I thoroughly enjoyed my time here at Ureki, reading and contemplating history, swimming in the Black Sea, eating my own body weight in 'kachapuri' (and even gloriously-filthier version of trabzon pide!) and getting far too drunk on the 2.5l bottles of beer! I was taken by the local red wines: Mukuzani and Saperavi. I did pass, however, at the offer of some home-made vodka, packaged in repurposed coke bottles. In general, the prices here were a bit of a pleasant surprise. I struggled to spend more than £5 on a full meal with drinks. Not surprisingly, English speakers were few and far between, and I made the effort to establish a little Georgian (mainly 'cheers' and 'where is the...' kind of stuff). After a few days here, I was fully recharged, with a spare few inches on my waistline. Time to catch the cross-country train and head eastwards to Georgia's capital! TbilisiThe train rolled into Tbilisi, and I stepped out onto the buzzing, bustling streets to find that - despite being even further east - the place had a distinctly 'western' air about it. Towering, almost baroque architecture, wide streets and glorious monuments. All this with a distinctly romantic and laid back - almost hippy-esque - vibe. Think Istanbul's vibe set to the backdrop of a mini Paris. English speakers chattering here and there meant I could largely retire my tortured Georgian skills, and I quickly got my bearings. Tbilisi is set in the floor of the Mt'k'vari river valley, whose sides rise like great walls immediately to the east and west. The city has has two core areas. First, Rustaveli Avenue, a monumental way named after the country's national bard, Shota Rustaveli, who lived in the 12th and 13th centuries. I will admit ignorance in this area, but I soon filled that gap, reading all about his life and works. More, I quickly added 'The Knight in the Panther's Skin' to my TBR pile, The avenue is the modern heart of the capital, lined with second-hand bookstalls, wine bars, boutiques, theatres and halls. Then there's old Tbilisi: a warren of lanes and markets, family kitchens, ultra-cool hippy tea rooms and ruins of the medieval walls, plus a spectacular 6th century AD fortress perched on a bluff commanding the Mt'k'vari River valley. While navigating on foot to my apartment, I quickly found out just how precipitous the city streets were. I really should have packed crampons! But then something quite memorable happened. I arrived at my apartment (Jonjolly Apartments - highly recommended) and met Mariam, who was there to give me the keys. She greeted me with a warm smile and then an apology: the apartment wasn't quite ready yet - it'd be another half hour or so before they had it tidied up. I was quite happy to sit on the doorstep and read, but she insisted on taking me to sample some Georgian wine. I assumed this meant a quick taster glass in a bar across the road. But no, she drove me to her favourite wine bar in the city and proceeded to ply me with 12 wine tasters and a range of snacks and appetisers: walnut and aubergine dips, freshly toasted flatbread, hummus, cheeses, cured meats and olives. Drool! Mariam couldn't have been more friendly or welcoming, chatting about her country's history and politics and asking about how things were in Scotland. I really enjoyed the conversation, and came to understand the strength of spirit of the Georgian people, and their sometimes fractious relationship with their giant neighbour in the north, Russia. It's always a bit daunting when you arrive in a new city for the first time, especially in a foreign country, but this was easily the most enjoyable welcome I've ever experienced. Maybe if was because of the 12 glasses of wine, but I decided then and there that Georgia was abshulutely bril-hic!-liant... The next day I woke, dazed, confused and glad I had already mapped out my itinerary a few days previously. First up, I visited Tbilisi Museum, packed with exhibits from the dawn of man right through to recent centuries - covering the eras of Persia, Rome, Greece, the Ottomans and Seljuks. Tantalisingly, there was a special display covering ancient Georgia's Colchis era, and the wealth of gold and in particular its proliferation of expert goldsmiths. This tied right in with my Hittite interests and potential that the Golden Fleece legend happened at the time of Empires of Bronze. The exhibits were simply breathtaking. The level of skill and creativity from so long ago really shifted my perceptions of history. More, they sowed a dragon's tooth or two in my mind, which may well spring to life in the later books of Empires of Bronze :-).  Back in the Bronze Age, Georgia was known as the Kingdom of Colchis, and it was famed for its reserves of precious minerals and metals - namely gold, which would have been mined from those mountains. More, this was the land which - legend had it - Jason and his Argonauts travelled to in search of the Golden Fleece. Intriguingly, this is thought to have happened in the decades prior to the Trojan War... exactly the time period in which Empires of Bronze begins (rubs hands excitedly). After the Museum, I sat in the 'Garden of the Republic' park and enjoyed a bit of shade, a sandwich and a read. I didn't realise just how much I would need the fuel... for the temperatures seemed to soar that afternoon, and the walk through the old town became steeper and steeper. And finally I saw the short distance that would lead me to Narikala fortress - a Persian stronghold built in the 6th c AD. Unfortunately this short distance was almost perfectly vertical. Perhaps I might have clicked that there was an easy way of getting up there, given the funiculars and cable cars zipping around overhead. but it was hot and I was still hungover, Thus I began hiking up my own mini-everest. Wonderful, eh? And the views from up on the fortress were even better. Here's a video - the final video of my trip - from up on those heights: Georgia Travel Tips

A full gallery of my journey through Georgia is available here on Facebook (Like and follow, please!) Quick navigation:

And Finally......the Great Hittite Trail adventure was at an end. Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed and/or drew some inspiration from this. Now go... explore! And if you're looking for an exciting Hittite adventure to read along the way...

1 Comment

The Eastern ExpressInto the unknown! That's how this leg of the expedition felt. An 18 hour sleeper-train across Eastern Turkey? The idea had thrilled me since I first planned it. I had notions of waking, parting my cabin curtains and seeing dawn pouring across the snow-capped Pontic Mountains, then whiling away the rest of the day gazing out of the window with my notepad and letting the muse take me. The reality? Booking a cabin on this famous train is very, very difficult. You have to wait until a few weeks before the journey before you can book, and the few cabins are sold out within moments of becoming available. Anyway, enough whingeing, I still got a berth, but just a normal train seat. Truth be told I almost didn't even make it onto the train. When my taxi dropped me off at Yerköy station, I had no ticket or confirmation. The TCDD app had confidently told me I needed only produce my passport to get my tickets at the station. Ha! Yerköy is a small town and the station was pretty basic. The chap in the ticket office - who had the patience of a saint - didn't speak a word of English, and I only command a really basic Turkish vocabulary, Google translate rode to the rescue - kind of. There were a few comedy mis-translations (one involving me claiming "I have already burned my tickets"). Good job I had got there 2 hours before the train's arrival because it took over one and a half hours to search the TCDD system and prove that I had bought tickets. Me and the station master actually did an ecstatic high five once we found them :) Famished, and having read the advice that the train sometimes didn't have much food on board, I grabbed a lamb pide and a bottle of juice. I assumed it was some kind of soft drink... then I noticed it was actually 'hot black carrot juice'? Eh?! Well, try everything once, I say. I did, and I won't be trying it again. It tasted something like spicy dishwater. Urk! Anyway, the train came, and I found my seat. Darkness had fallen by this point, so there was no sightseeing to be done. As the train moved off, I tried to make myself comfortable - the seats were big and comfy, but it was still above 20 degrees Celsius, and I knew 18 hours would be a test. So I flicked on my Kindle. About half an hour in, a voice stirred me from my reading. I looked up to see a smiling young woman, holding out a box towards me. 'For you' she said. Confused, I took it, opened it and beheld the cakes and pastries it contained. She was away before I could thank her. Just to be clear: she was not a member of the train staff - she was just being very, very kind. I saw other people doing similar things: offering each other food and drinks from their own personal stashes. Indeed, later on another family boarded at Kayseri station, and they proceeded to give me a potato! I think they thought this was quite funny because I'm from Britain and all British people are (apparently) crazy for potatoes! A while after this I spotted the kind cake woman and gave her a pack of haribo for her young daughter. This whole communal atmosphere really softened what was to be a tiring journey. With nothing but the darkness of night outside, time wound on lethargically, and - unable to lie down - I simply couldn't sleep. I was exhausted and on the edge of full grumpiness when something wonderful happened. Dawn. The Turkish sunrise. Beauty emerging from darkness like an amber teardrop. This was the vision I had been waiting for. Silhouetted hills, rolling dusty plains, Cliffs and crags. These were the lands that the Hittites once roamed, honouring the spirits of every rock, wood and vale. And the landscape changed after a time. The train plunged into mountainside tunnels, emerging into successively rockier and more lofty ranges - chiselled walls of terracotta that stretched for the sky - some capped with snow even though the ground-level heat remained sweltering. For every height there was a matching ravine, with opaque, emerald brooks, fed by toppling, silvery waterfalls. Now I was in my element! I left my seat behind and began patrolling the train in search of good windows from which I could take photos or simply observe (and wait for the muse to come!). It was simply magical, and at one point I was entranced by a green river and the way the sunlight was sparkling on its surface... then I realised (with a quick check of the map) that it was actually the upper Euphrates - one of the most famous and ancient rivers in the world. The highlight - by far - was my find of the mail carriage. It was deserted. No mail bags, no furniture - just an empty shell of a carriage... with huge doors on either side, lying wide open! So, with a form grip on the rail next to the door and my camera set to video mode, I tried to capture the moment... ErzerumMy train journey ended at the city of Erzerum, which deserves a special mention because - although it is small and not quite the 'beautiful' tourist city, it is very authentically Turkish, and that is what I was here to see. I only had a short overnight here, but I did manage to browse the historic city centre and its very wonderful mosque and medrese. Even better, I was introduced to a Trabzon Pide here - a deliciously calorific cheese, egg and bread concoction that went wonderfully with a chilled pint of Efes :) Just before I left to catch the bus onwards to Georgia, I had a moment of reflection, and realised that a few of my books had criss-crossed this ancient city, as my video will try to explain: Eastern Turkey Travel Tips

A full gallery of my journey through Eastern Turkey is available here on Facebook (Like and follow, please!) Quick navigation:

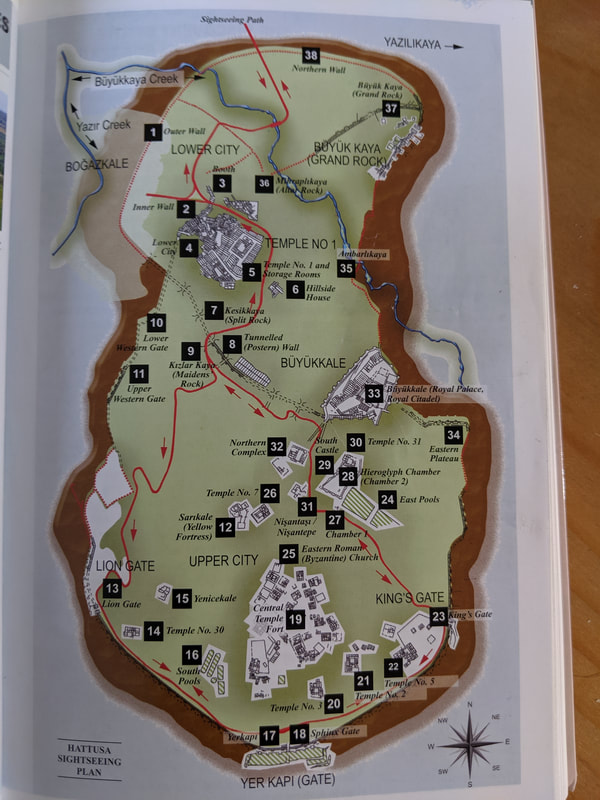

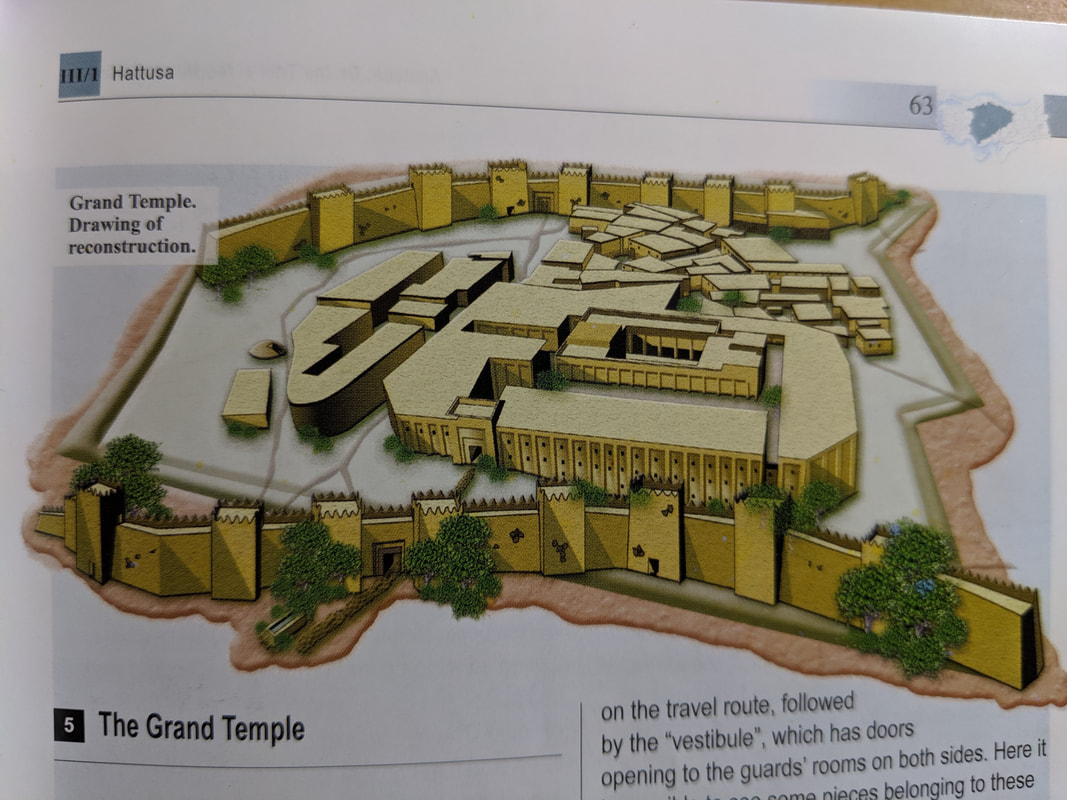

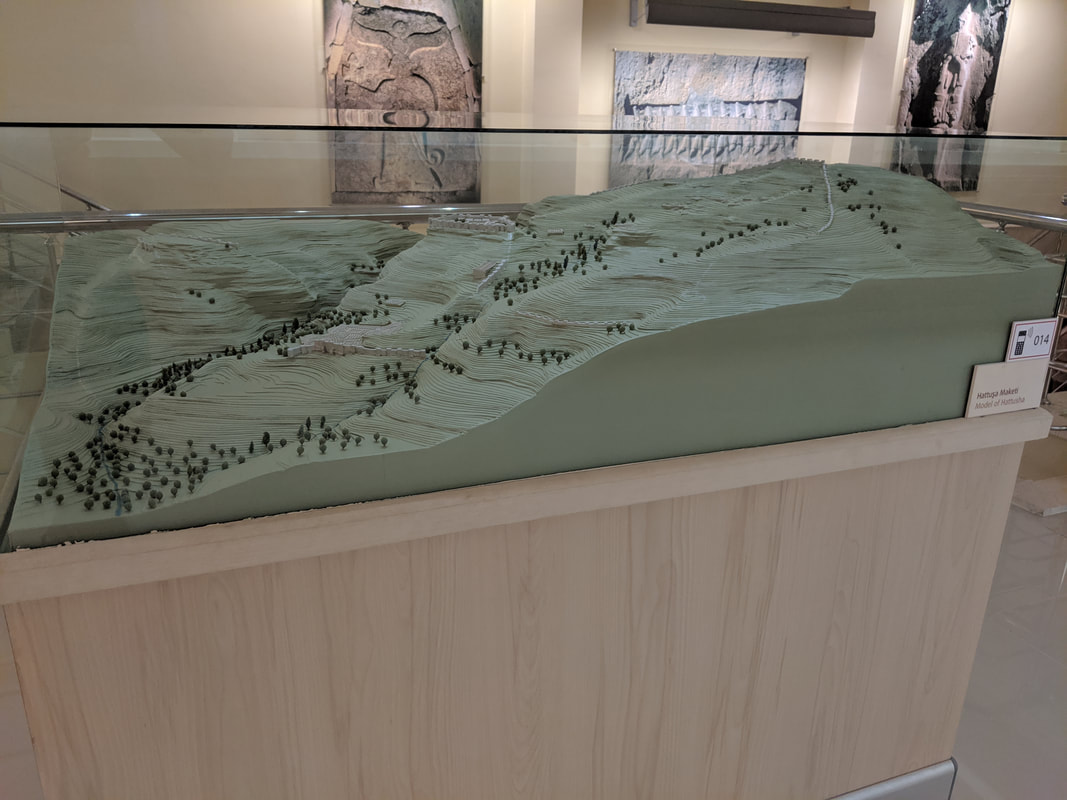

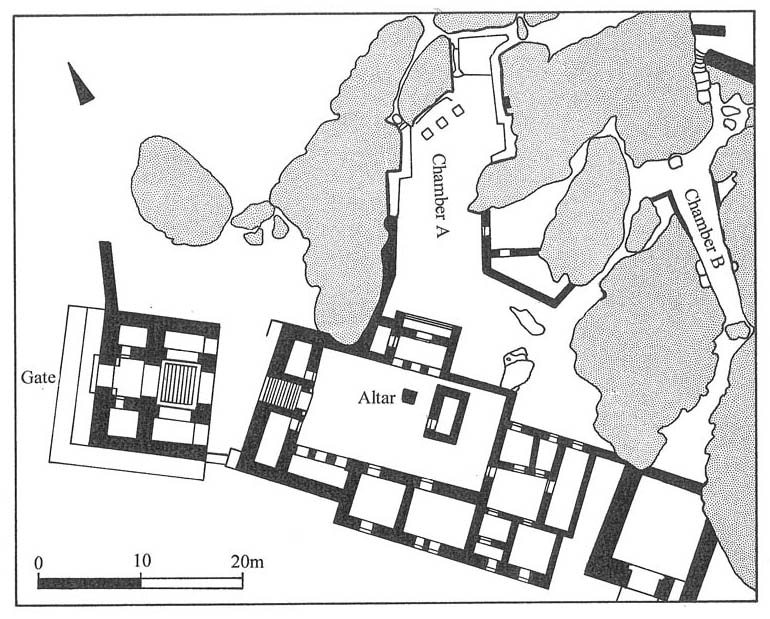

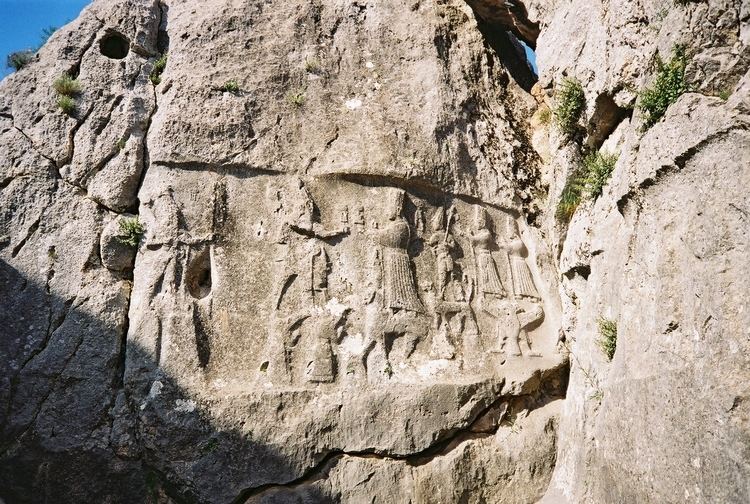

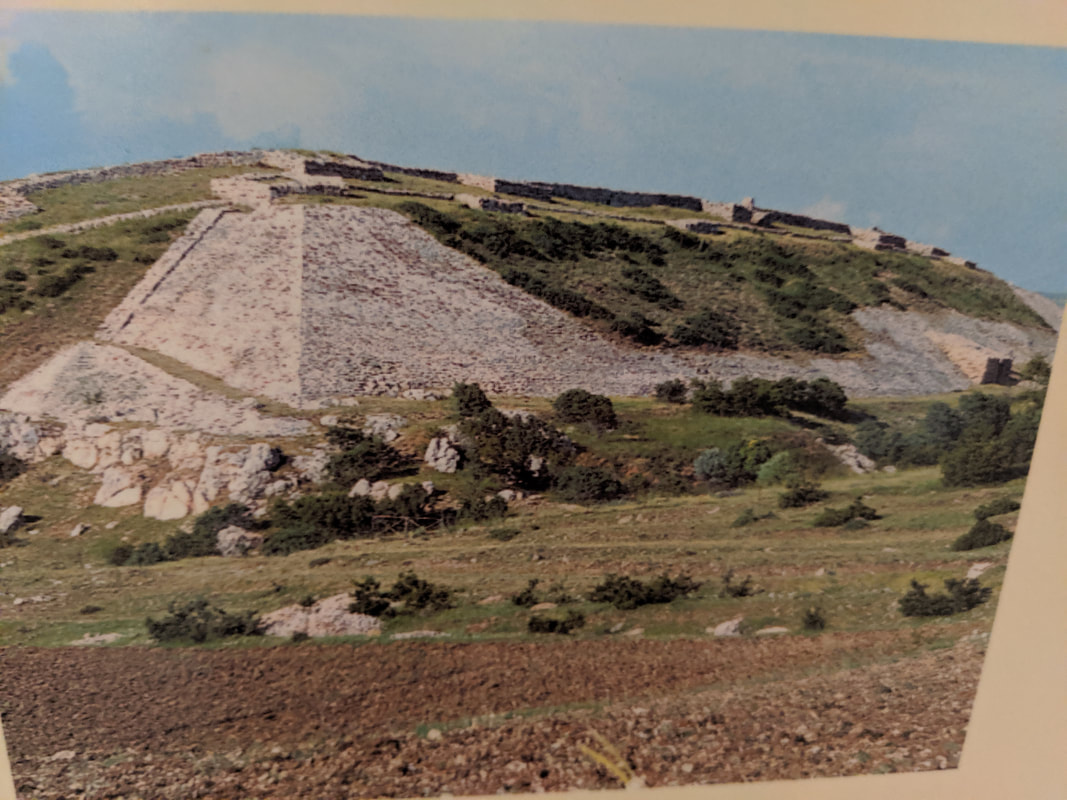

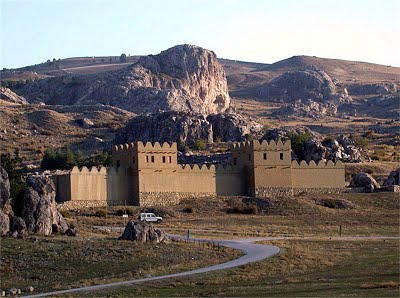

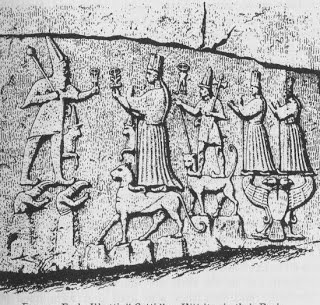

Hattusa. This place had haunted my days and dreams for over six years. I had pieced it together mentally thanks to a variety of maps and photographs online, but I had craved this moment, to be here where 3,000 years ago the Hittite Empire flourished. All the way on the 3 hour bus from Ankara to Sungurlu, then again during the dolmus ride towards the town of Boğazkale, I scoured the horizons, waiting, eager, watching sierras and cliffs rise then peel away as we sped closer and closer. Would I even recognise the mountainside of Hattusa amongst this highland region? But the moment the rolling, rocky masif arose from the eastern skyline, I felt a hot thrill of recognition - a great sense of arrival. 'That's it!' I proclaimed - somewhat startling the elderly Turkish gent in the dolmus seat in front of me. 'Look, see the ravine - that's cut by the Ambarlikaya river. The tor on the right - that's the acropolis. And on the left, that's Tarhunda's Shoulder!' I gibbered away to anyone who was interested. The dolmus pulled into the small town of Boğazkale, situated at the western foot of the mountain ruins. I hopped out, dropped my bags into the excellent Hittite Houses hotel. Sitting in the leafy shade of the hotel gardens, I wolfed down a quick lunch of bread and tomatoes, before arming myself with my backpack - water, headscarf, camera being the usual essentials. And there was one other thing vital to this walking tour: the guide book I had bought in the Ankara Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. It's perfect - containing a route map and concise but informative explanations of the ruins on show at every step. Off I went on the short (~1km) walk up the quiet country road that leads to the ruin site. But like all adventurers, I was waylaid by two almost impassable obstacles. First: a wild cherry tree, heavy with fat, glinting, red and ripe fruit. I simply had to stop and stuff my face with these. Never in my life have I tasted cherries as pleasant as these ones. Next up, I was assailed by a ferocious monster! Not quite. It was actually a wild tortoise, ambling across the middle of the road. I don't know how often traffic passes along this road, but I wasn't minded to leave the wee fella like that, so I lifted him over to the side of the track he was headed for. Tortoises tamed and cherries guzzled, I rounded the bend in the track and entered a pleasant stip of shade cast by a stand of pine and birch trees. The sound of a high breeze, sussurating through the branches provided an extra sensation of coolness. But then I heard something else: running water. I knew what this was before I saw it - the Ambarlikaya (or River Ambar, as I call it in Empires of Bronze). This was the waterway - sacred to the Hittites - that ran through their capital all those years ago and still does even now. This is where Prince Hattu and his brother Muwa, swam and played as children. This is where the Wise Women of the Hittite Empire would have prayed and divined. A few hundred yards on the trees opened up and I once saw the site before me. Dominant in the foreground was the stretch of reconstructed lower town walls. These stout defences would have run for some 7 miles all around the mountainside. Walking around HattusaSo here I was! Hattusa was first 'discovered' by Charles Texier in 1834. Seemingly he was stunned by the place and it's sheer scale and architectural ambition - and I could see why: the interior wards and fortifications of the city are built on the most precipitous of rocks and crags, and the expanse of the place simply blew me away. Here's a vid of my first impressions: I got my bearings then began to follow the route map in my guide book. First, I came past the Storm Temple - the greatest and most sacred of the many Hittite temples. This one was - as the name suggests - built to honour the Hittite Storm God, Tarhunda. Like all Hittite temples, the focal point was an open-air central plaza, at the corners of which niche-rooms housed statues of Tarhunda himself and his divine wife Arinniti, Goddess of the Sun. More, the temple was ringed by a huge ward of warehouses and workshops, where the clergy and temple artisans lived and worked. After the Storm Temple, the path leads steeply uphill, through the foundation ruins of the original city's outer walls and ascending to the later 'Upper City'. All the way, the Hititte fondness for ultra-ambitious architecture stunned me. There were gates perched on bluff edges and forts planted up on towering rocky pillars like eagle's eyries. Rather stirring was the sight of a falcon soaring up on the thermals. I felt a true frisson of emotion then, wondering if Hattu might have watched his pet falcons fly like this, right here. Approaching the high-point of the Upper City's southern reaches, I came to a run of three mighty gateways that took the breath away (or maybe that was just because I was a bit out of puff!) The wind at this height was buffeting but pleasant at least in that it took the edge from the blistering heat of the sun. The 'Upper City' was built in the time of our hero, Hattu from Empires of Bronze. This extension to the capital was spread all across the sprawling heights to the south of the original city, doubling the size of the place. The strange thing is, the new ward is comprised almost entirely of temples. Scores of them. And atop the high outcrops of rock between the temples, the Hittites built lofty fortresses. Yerikale and Sarikale (yellow castle) are the two most impressive of these. And the whole Upper City region was encompassed in massive buttress walls - double-layered in places. So why the many temples and fortresses? Why the sudden need to double the city's size? Those are the questions I examine in this next video: Down through past the Upper City's eastern walls we came, past hieroglpyh chambers and more temple ruins, back into the original city before finally approaching the acropolis. This was the centre of the capital - the fortified residence of the Hittite Labarna. Here, foreign kings would have come to pay homage to their Hittite master in a grand hall. Here, Hattu, his ancestors, father, brothers and children would have lived. Here's my video, taken up on the acropolis. I try to summarise my thoughts and feelings about the place on what had been an incredible day. After so long, I had finally walked the same ground as Hattu and the line of Hittite Kings! After nearly 15k of walking - most of it steeply uphill - I felt surprisingly fresh, But on the way back to my hotel - probably once the adrenalin started to subside - my legs began to ache. When I reached the hotel, Denis, the owner, was running a birthday party for his young son. I sat down in a quiet part of the restaurant, ordering and enjoying a delicious meal of doner and rice with an ice-cold beer. Then Denis came over, kindly bringing me a bowl of popcorn and a giant slice of birthday cake to enjoy :) Off to bed I went, replete, exhausted... and exhilarated. Yazilikaya - The Great Rock ShrineThe next day, I awoke feeling stecky (a Scottish term meaning stiff) but well-rested, I sat on the porch of my room in the morning sunshine, enjoying a traditional Turkish breakfast of tomatoes, cucumber, olives and cheese, along with fresh apricots from Denis' orchard and a super-strength coffee! I was due to leave later on in the day after this all-too-short visit, but I still had time to see two more close-by and crucial Hittite sites. First up, Yazilikaya - the ancient Rock Shrine out in the nearby countryside. The walk from Boğazkale to Yazilikaya is about 3km. not too bad, but in 30 degree heat and with zero shade... and all sharply uphill, you'd be advised to take the usual hat, water and good walking shoes. All that aside, the trek there is pretty special. I did it on a perfectly still summer's day, along the winding tarmac road that rises past Hattusa's northernmost promontory (Tarhunda's Shoulder), giving excellent views of the precipitous battlements on that end of the city, and then splendid vistas across the countryside near Hattusa. I did this in July, and the land to the west was a patchwork of rolling green, gold and hazy terracotta and grey nearer the horizon. The fields were freckled with poppies, buttercups and tulips and misted with a haze of butterflies. East and south was dominated by the Hattusa massif... but northwards was strange - a green and constantly rising land, studded with silvery warts of rock. One of which stood proud, and I knew - just as I knew when I saw Hattusa from a distance - that I had arrived at the famous rock shrine. Yazilikaya, literally 'The Written Rock' is rather aptly named, for some of the finest extant Hittite reliefs are to be found here. They venerated this place almost as much as the great Storm Temple in Hattusa. During Hittite times the steps (see the image, above) would have been covered with a vestibule of sorts which would have led right up to the jagged 'crown' of rock on the left of the pic. Inside the 'crown' sit two roofless chambers (known as A & B), adorned with images of Hittite Gods, Kings and legends. The place was embellished throughout the reign of the Hittites, with some of the final modifications dated to the very last of the Hittite Kings. Here's my video of 'Chamber A', along with some 'Haga-spotting' :) ... and then some pics from within the shrine. The Hattusa MuseumAfter Yazilikaya, I headed back into Boğazkale, and to the Hittite Museum there. It is small-ish but thoughtfully laid out inside, and it does a fine job of telling the Hittite 'story' It also houses Roman, Byzantine and Phrygian finds from the local area, but it is first and foremost a Hittite exhibition. Here are some of my best pics: Brimming with facts and ideas, I left the museum behind (dropping off more of my bookmarks on the way out!) and caught a lift to the nearby town of Yerköy, where I was scheduled to catch the famous 'Eastern Express' sleeper train that would take me across Turkey - right through the ancient Hittite heartlands - and to the country's eastern edge. The next part of this blog series will chart my rail-based adventures! Hattusa Travel Tips

A full gallery of my visit to Hattusa is available here on Facebook (Like and follow, please!) Quick navigation:

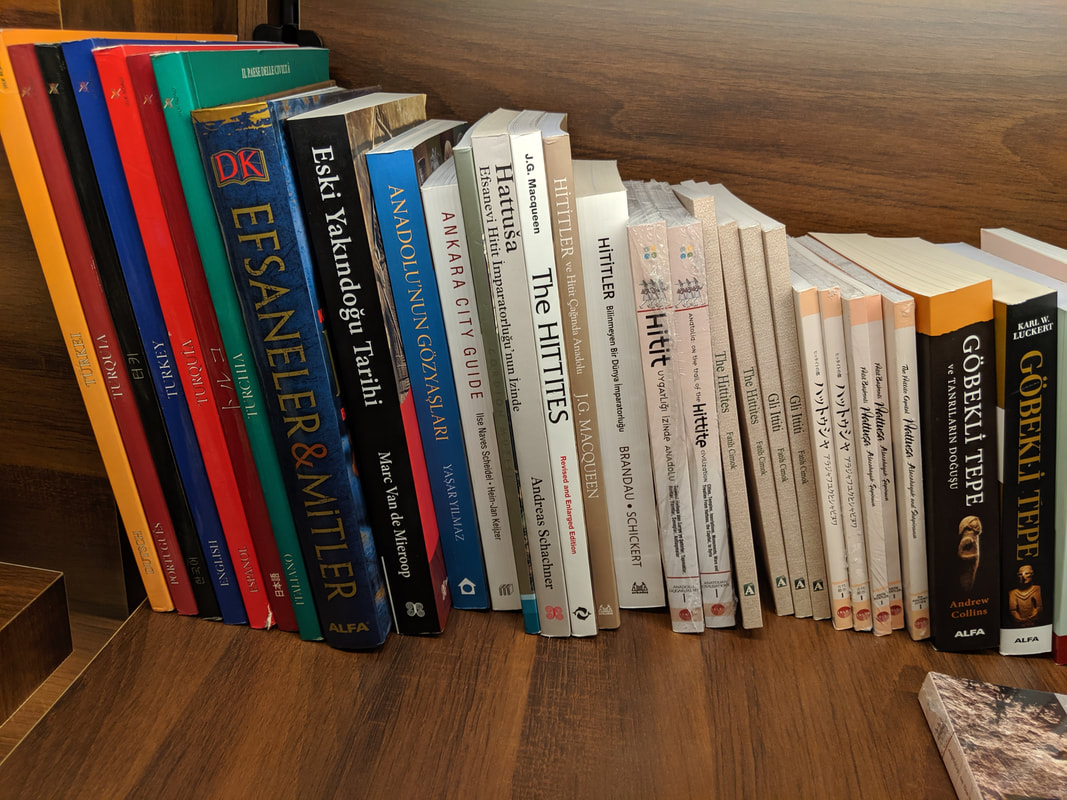

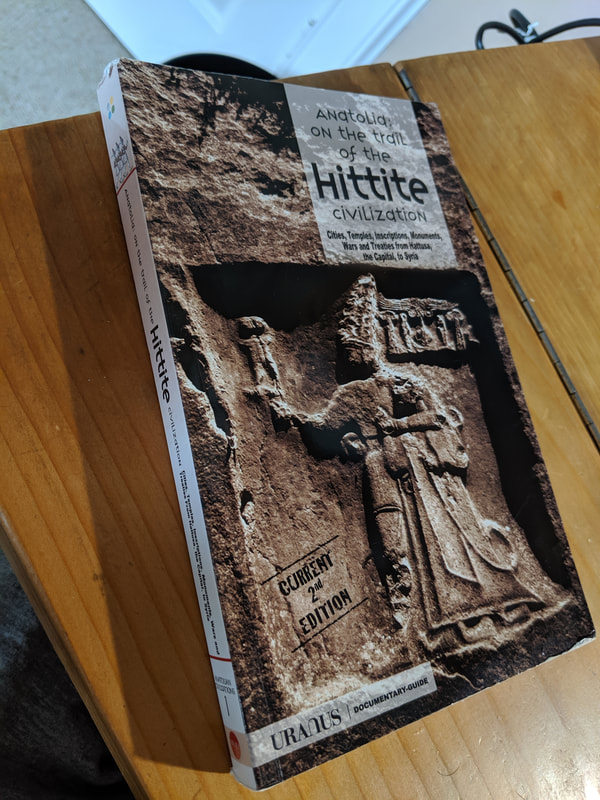

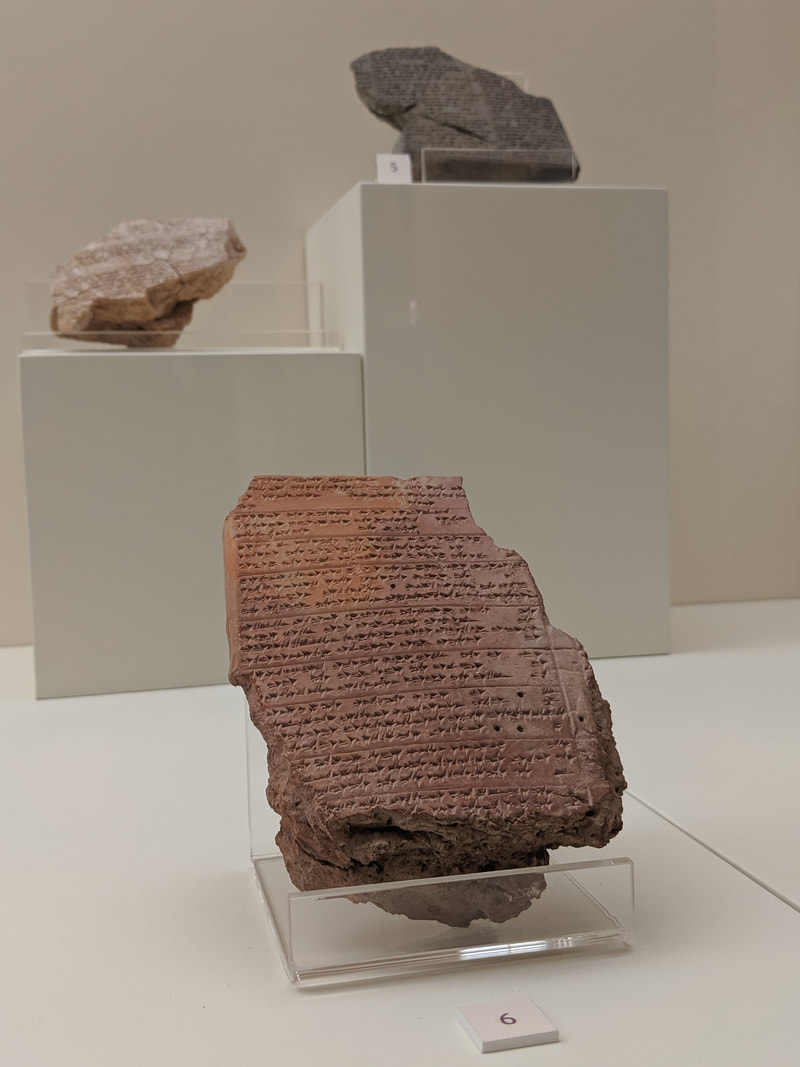

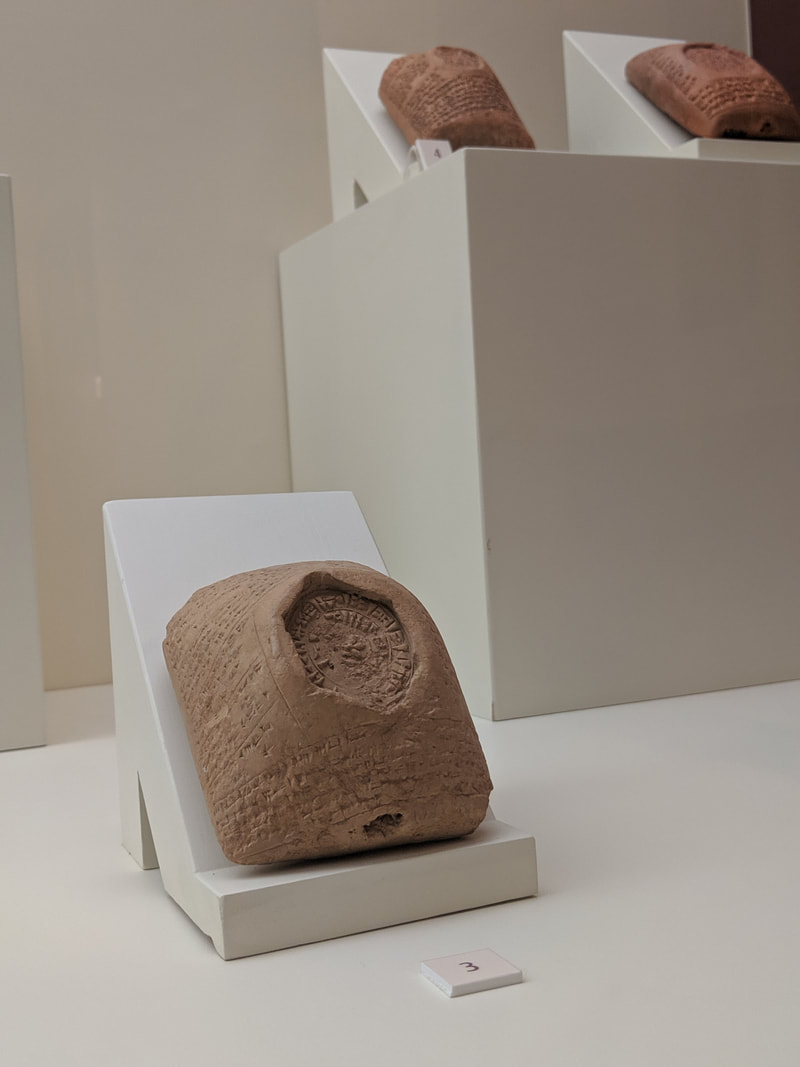

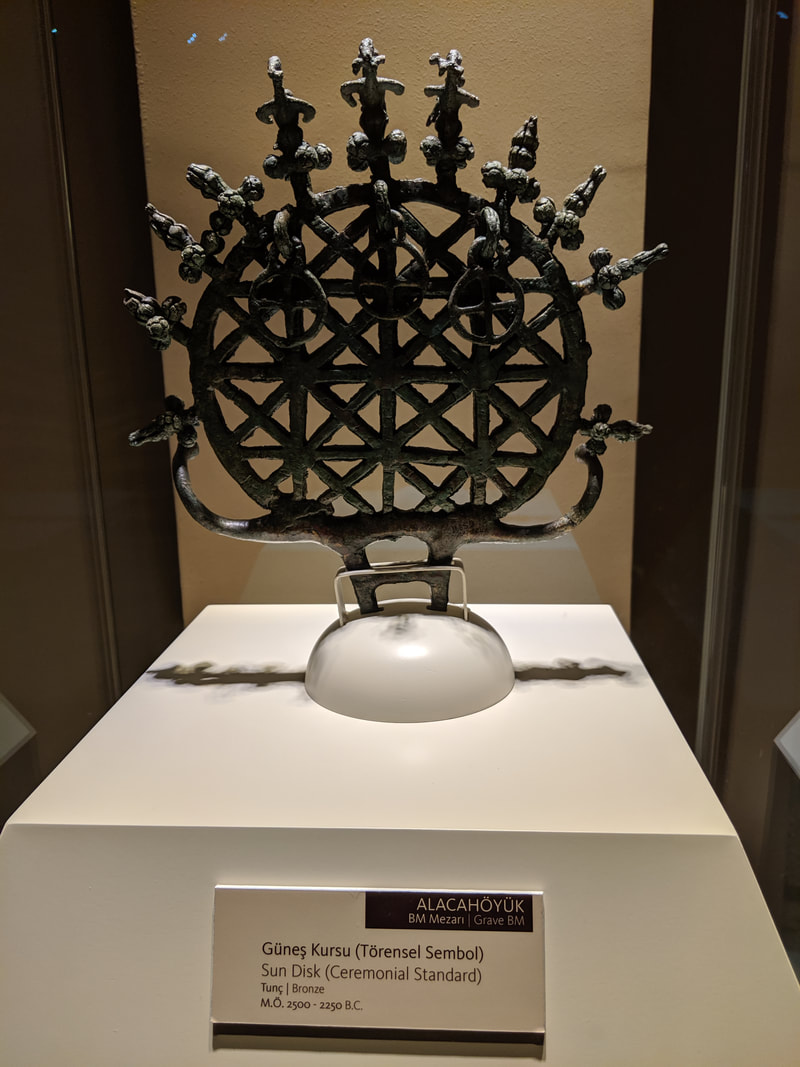

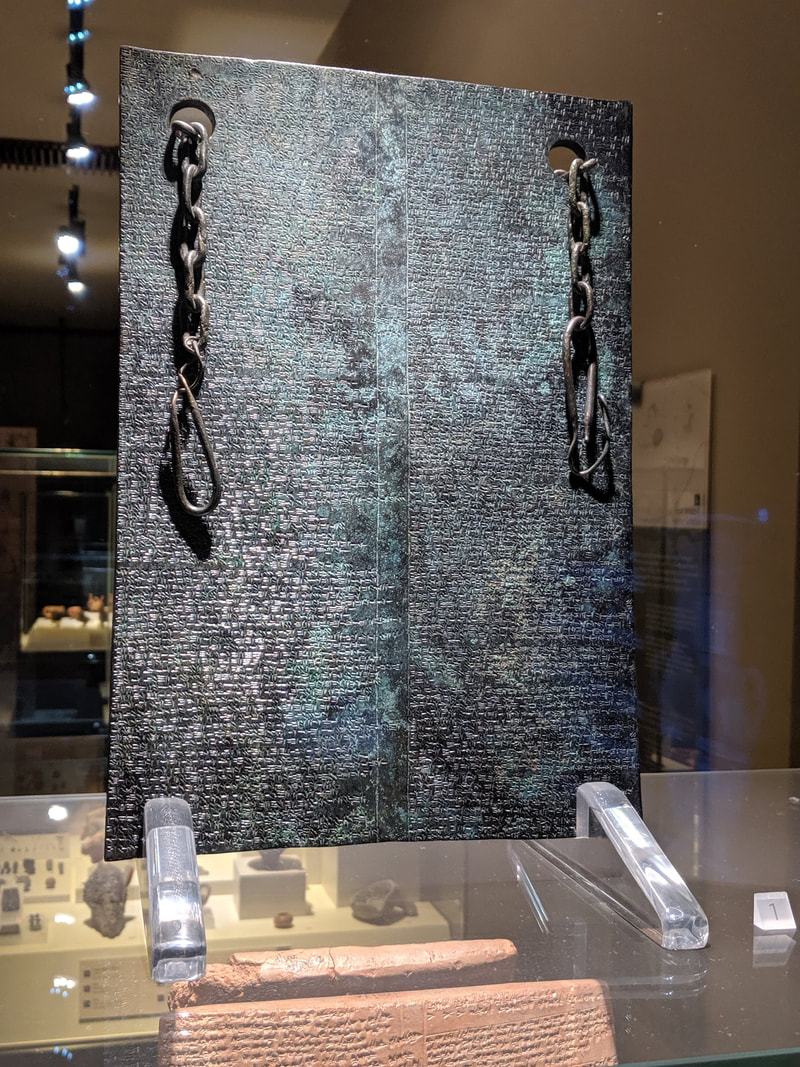

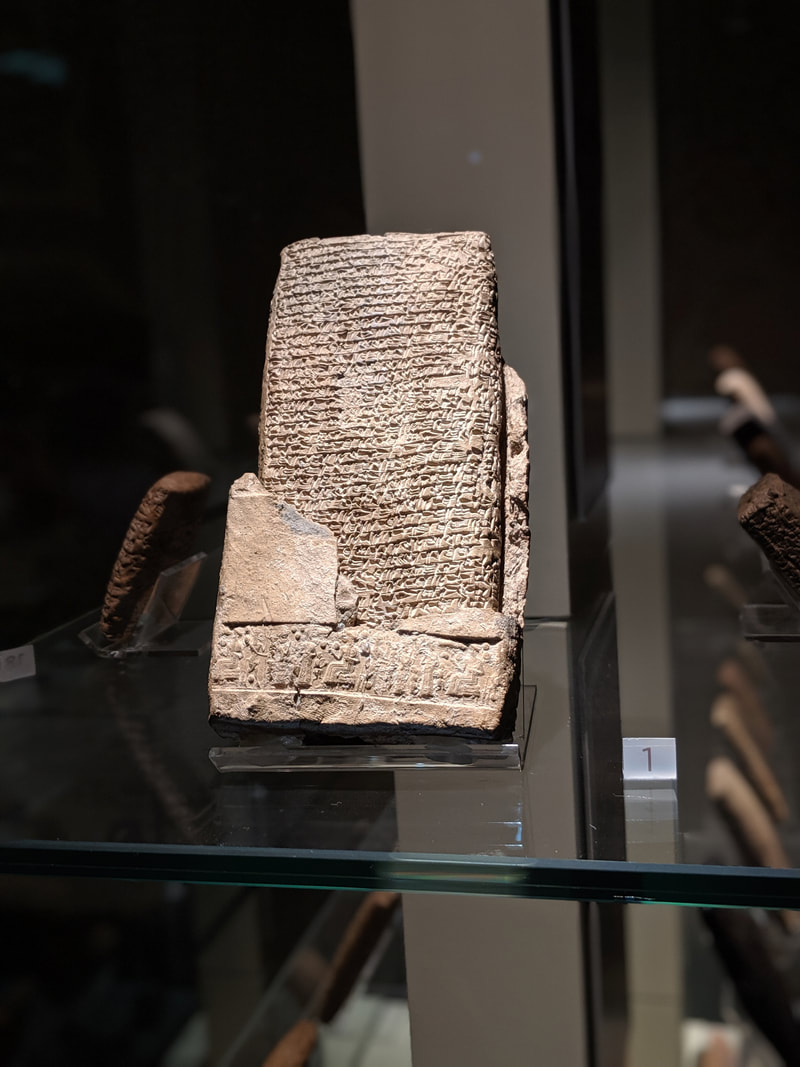

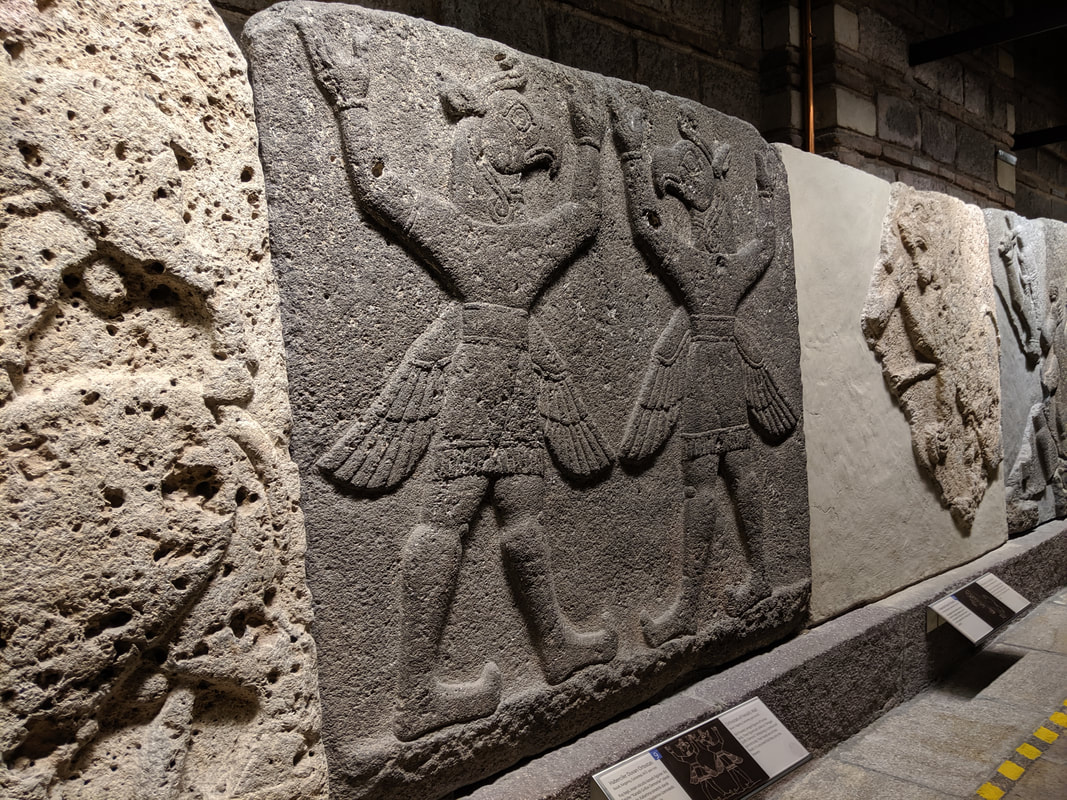

Despite many visits to Turkey, this was my first proper foray across the country's interior, and it began on the high speed train from Istanbul's Karikoy region (the part on the Asian side of the city). We whizzed through the outer suburbs of the city and soon we were in a green, hilly paradise. It brought to mind Seton Lloyd's description of the Turkish landmass: "Anatolia is like an open left hand, palm upturned, with the thumb curled inwards to represent the Taurus Mountains in the southeast. The palm represents the central plateau and the heel of the hand the eastern massif, and the fingers the diminishing ranges which extend westward to find their echo in the islands of the Aegean" Speeding towards Ankara on the train, we were traversing the land of valleys and rivers - the 'fingers' of Lloyd's useful mnemonic. With every mile we travelled, we were also climbing - because we were headed towards that central plateau, a rugged land ranging from 2,000-10,000 feet above sea level... the heartland of the Hittite Empire. I settled back, popped in my earphones to listen to an H.G. Wells audiobook (War of the Worlds) and drank in the views of the wooded hills, river vales and hazy summer sky. Having paid a whole 36 Turkish Lira (roughly £4.50) for this 4 hour train trip, I had in my backpack a bottle of water and a rather uninspiring pretzel. After all, this was economy class, so you have to bring your own grub, right? Wrong! The trolley chap came along and started loading food onto my table: fruit juice, fresh bread, dried apricots, olives, salad, cheeses, cakes, coffee... a veritable feast - all complimentary with the economy service. I'm not sure he understood why I started gibbering in gratitude, but thankful I was and I munched away for the next hour of the trip. As we gradually ascended onto the inner plateau, I was reminded of another traveller's description of the changing landscape. Gertrude Bell, writer and archaeologist said: "Before me stretch wide plains, corn-growing where rainfall and springs permit, often enough barren save for a dry scrub of aromatic herbs, or flecked with shining miles of saline deposit; naked ranges of mountains stand sentinel over this expanse" Very evocative! I really did feel like I was entering a different land - cooler (still sweltering though) higher and differently shaped. And the city of Ankara itself is very different to Istanbul. Smaller - just the 5 million people here! - and with a very different vibe. It isn't as 'pretty' as Istanbul, but it does have its own type of ascetic beauty. Spread across the wide open hills and plains like a defiant outpost it more accurately personifies Turkey as a country. Another bonus is that the prices here are vastly cheaper than in Istanbul. After arriving in central Ankara, I enjoyed a lunch of tasty doner kebab and cold coke which cost less than 2 quid, and the '2017 hotel' (breakfast included) cost £20 per night - good value for a traveller on a budget. First, I had to visit the Anitkabir - an iconic structure that defines modern Turkey, and has Hittite connections. I'll let my YouTube vid explain: But the main reason I was here in Ankara was for its famed Museum of Anatolian Civilizations - an absolute treasure trove of history, with exhibits ranging from the stone age, the Hittite period and all the way through to Byzantine times. I wasn't sure just how much Hittite stuff I would find here. What if the Hittite collection amounted to no more than a few bits and pieces? So I was absolutely thrilled to see, on my approach, this giant replica of a Hittite totem (known as a huwasi)... as well as some other rather light-hearted Hittite references... Inside the museum was even better. Laid out in successive epochs, starting with the paleolithic era, it beautifully tells Anatolia's story with a selection of glass-case artefacts, interactive big screens and tableau recreations of ancient homes. I could actually 'see' Hittite culture emerging into history, especially with the variety of sun disc artefacts dating from the late 3rd/early 2nd millenium BC. The sun disc would go on to become a Hittite royal symbol by around 1600 BC. Then I came to the Hittite section proper. The first thing that struck me was the number of tablets. Beautiful and majestic things. Whole and undamaged unlike the Kadesh treaty. There was even one incredible bronze slab, laced with chains, authored by King Tudhaliya IV, son of our hero, Hattu.  The mark mde by a Hittite royal stamp seal. The Hittite King (the Labarna) would press his seal into the soft clay to 'sign' important tablets before they were baked hard. Note the mix of cuneiform a-script around the edges of the seal-marking, and the hieroglyphs in the centre. This is why we know it is a royal seal, as only Hittite Kings were allowed to use script and glyphs. The hieroglyphs show a winged sun disc. Below each wing tip we see the great king symbol. The tall triangle represents an ordinary king, and the kidney-shape on top makes it a 'great' king. Also... this seal probably belonged to a certain King Urhi-Teshub... There were statues of the sacred twin Hittite bulls too - Serris and Hurris. There were drinking vessels, seals, brooches, rather detailed wedding night manuals* painted in the sides of vases. The world that had existed in my head until now was real, tangible... right before my eyes. *I'll leave the details to your imagination :) A bronze handled sword with an iron blade. A very interesting find and one that stokes the old 'did the Hittites use iron weapons' debate. And then there were the architectural pieces. Great monoliths carved with the figures of Hittite Gods. Orthostats (stone slabs that once clad Hittite walls and gates) engraved with scenes of ancient legends such as Gilgamesh, or depictions of marching Hittite warriors, More lions, griffins and winged bulls too. I happily snapped away with my camera, all the while thinking just how close the next stop of my adventure was. Hattusa, capital of the Hittites, where many of these treasures came from, was but a few hours away ;)  A nice selection of literature in the museum shop. I picked up a copy of "Anatolia: on the trail of the Hittite Civilization" (in the middle), as it included a perfect guide to a walking visit around Hattusa... the next leg of my adventure! I also left a pile of Empires of Bronze bookmarks with the staff here :) But first, a little bit of Roman research...Before heading to Hattusa, I had to see what other historical gems I could spot here in Ankara. In this respect, a stroll into downtown Ankara is well worth it if you have the time. I found the Column of Julian the Apostate, the Temple of Augustus and the Great Baths of Caracalla (infuriatingly closed minutes before I arrived, but I still managed to get a few shots through the fence). Check it out: All of the above sightseeing was spliced pleasantly with turkish coffee and baklava in the shade of street side cafes. A lovely way to round up the Ankara leg of the trip. Next up... Hattusa, the heart of the Hittite Empire! Ankara Travel Tips

A full gallery of my visit to Ankara is available here on Facebook (Like and follow, please!) Quick navigation:

Gordon Doherty is the author of the Empires of Bronze series, available in eBook, paperback and audiobook formats. The Journey of a Lifetime

For the last few decades I have developed an unhealthy obsession with The Aegean and Turkey - a land riddled with history, steeped in legend and lore. Every book I have written has been set in or around that region. I have been fortunate enough to enjoy a number of forays around the lands of Constantinople (Istanbul), Greece, southern Thrace (European Turkey and Bulgaria) and around Turkey's western and southern coastal regions. But apart from a few expeditions inland - to Pergamum, Ephesus and Pamukkale, I had never yet truly penetrated the rugged interior or north of Turkey.

Madness! Considering my Strategos trilogy was set up there in the borderlands between the Byzantine and Seljuk domains. Insanity! Given my new Hittite series, Empires of Bronze, was based up there too. And it's this current series that drove me to finally plan and execute this adventure - a trip that would take me from Istanbul, three millenia ago the western edge of the Hittite realm, to Georgia, on the eastern periphery of the ancient Hittite world. So join me in my travels across this ancient land as I seek out remnants of the once-great and long lost civilization of the Hittites. Join me... on the Great Hittite Trail!

An interactive Google Map of my journey, across northern Turkey and into Georgia, passing through some key Hittite sites along the way ( with all the landmarks, train stations, hotels, restaurants etc pinned for reference.).

Istanbul, Byzantium, Constantinople... the City

Where else to begin the journey, but in the place known to countless millions simply as 'the city'? I've been to this ancient metropolis a number of times now. On every single occassion I have been struck dumb by the aura of the place. It's something sensory and spiritual at once: the balmy heat on the skin, the scent of spices and roasting meats, the storm of colours and spectrum of architecture, the crash of the waves on the sea walls and the other-wordly paean of the call to prayer that - every single time I hear it - sends shivers of awe up my spine as I think back through the many civilizations who have inhabited this hilly peninsula, the people who have walked here, who have lived and died here. Their lives, their stories.

It's always the Hippodrome region that gets me most of all - something about the open space and how it allows the hustle and bustle of the city to just glide over me like a gentle breeze. I could sit there for hours and hours and just contemplate. And while I was here I did just that - equipped with my Kindle, a tasty kebab and a few cold drinks (and abetted in my eating efforts by some of the local street cats).

There are so many Roman and Byzantine ruins to see here (covered in my Walking Through Constantinople blog), but this time I was here in search of the Hittites! The site of Istanbul probably hosted a village or small citadel back in the Bronze Age, but whatever was here in those days was never part of the Hititte Empire, The Hittite 'realm' stretched across most of Anatolia (Asian Turkey), and controlled a ring of vassal kingdoms around its periphery. The closest of those vassals would have been Troy, just across the Sea of Marmara.

So why was I here if there was no direct Hittite connection?

One, because it's where my plane landed! Two, because I adore this city and Three... because there is one monumental Hittite artefact here... let me explain: The Istanbul Archaeological Museum is a must-see. I've been round it several times to take it all in: there is the Alexander Sarcophagus, pieces of Pergamon's Temple of Zeus, Exhibits from Troy, parts of the Gates of Babylon. Roman statues and military remains, Byzantine naval reconstructions. Relics, artefacts... everything. And the one thing I had neglected to pay due attention to on all those previous visits: the Hititte-Egyptian Peace Treaty of Kadesh.

So what's the significance of this treaty? Well, over 3,000 years ago, the Hittites and the Egyptians were the superpowers of their day. When they went to war - as one old Turkish man described it to me - it was the real first world war. Everyone was dragged to battle with one side or the other. Kingdoms and nomadic tribes were compelled to march with the Hittite Labarna or the Egyptian Pharaoh. They met at a place called Kadesh in modern-day Syria. On that baking field of combat, they nearly destroyed one another. Both sides boasted of victory, and then came to realise, slowly and horribly, that they had each in fact lost immeasurably.

Years later, both still traumatised by the clash, the great states came together and agreed the remarkable treaty of peace and harmony. Neither wanted to see a repeat of that great war. The Hittite version of the treaty was originally recorded on a great silver slab. But the Hittites were meticulous in their record-keeping, and copies were made. We know this because the tablet that survives to this day is a copy, written on a slab of baked clay. When the clay was wet and soft, the Hittite scribes would have marked the treaty details into the clay using a wedge in a writing system known as cuneiform a-script, before putting the clay in kiln to bake it hard and dry. The language on the treaty is very evocative, and the desire for true peace shines through.

"Let the people of Egypt be united in friendship with the Hittites. Let a like friendship and a like concord subsist in such manner for ever. Never let enmity rise between them."

What is remarkable, surprising and at the same time, perfectly apt, is that a copy of this tablet stands proudly on display at the Security Council Chamber of the United Nations in New York - as an example of altruistic peace between nations.

Most electrifying of all was the fact that Hattu - the protagonist in Empires of Bronze - would have been involved in the writing of this tablet, and would almost certainly have held it and rolled his sylinder seal along the completed copy before it was baked. I must admit it brought a lump to my throat to think of that strange temporal bridge, three thousand years long, between me and him. What a poignant and amazing start to my Hittite adventure!

I spent the rest of my few days in Istanbul touring some of my favourite Roman and Byzantine sites and some that I had previously been unable to get to. The Column of Marcian, erected in the 5th century AD in honour of the eponymous emperor, was a wonderful find - nestled away in the tight streets between Istanbul's Fatih and Eminönü wards.

After snapping away with my camera for a while, I felt the afternoon sun growing a little too strong (it was hot that day!) so I retreated to a nearby street cafe, ordered a Turkish coffee (think you've had strong coffee? think again!) and admired the marble column from the pleasant shade.

On my way back to my hotel (Naz Wooden House hotel - charming and very affordable if basic) in the historic centre of Istanbul (the Sultanahmet district), I passed through a quite incredible street celebration - more like a show of defiance - about the recent election results which had confirmed President Erdogan's loss of Istanbul. The atmosphere here was absolutely electric, with skirling zurna pipes, banging drums, crowds chanting and dancing, punching the air. Great banners of Atatürk - Turkey's founding president whose manifesto was something of an antithesis to Erdoğan's policies - fluttered in the air over all of this.

By the time I got through the crowds and back to the Sultanahment region I was so hot and sweaty I decided to go for a haircut to help cool me down. It was a vigorous and quite enjoyable experience involving hot towels, lemon juice, matches and all sorts of implements. The end result was a shorn and much cooler head :)

The following day I skirted around the magnificent Valens Aqueduct - the scene for some vertigo-inducing combat in Legionary: The Blood Road - before stopping for a must-have Istanbul lunch: a freshly caught fish sandwich (who knew sandwiches could swim?) at the run of cafes under the Galata Bridge, overlooking the Golden Horn.

In the afternoon, I finally got a chance to visit one of the city's many subterranean Roman cisterns that had previously eluded me. The Binbirdirek Cistern (the name is Turkish for 'Cistern of 1001 columns') was constructed in the reign of Constantine the Great in order to supply water to the Imperial Palace. It's less well known and maintained than the Basilica Cistern, and on my visit there was nobody else there at all! But that made it all the more atmospheric for me. The weakly uplit vaults, the smell of dampness and the starngely muted echoes of my footsteps and breaths gave me a strange sense that I was not alone down there. The experience was all I hoped it might be - and I even came back out with a creepy book scene planned out in my head. Crazy to think that the place was used as a rubbish dump for centuries.

The last evening in Istanbul was rather pleasant. After enjoying a meal of sea bass and wine on a rooftop terrace overlooking the Bosphorus, I then decided to wander down to the Palatium cafe - a splendid and very relaxed place with an incredible glass floor looking down upon the excavated ruins of the Magnaura Roman Palace. So I had to stay for a while, didn't I? I had no option but to have several beers, did I? I was practically obliged to try a Shisha pipe for the first time, wasn't I?

Anyway, dizzy from beer and smoke but aware that I needed to be up early to catch the train to Ankara, I headed back to my apartment... only to be accosted by this little chap!

Istanbul Travel Tips

A full gallery of my visit to Istanbul is available here on Facebook (Like and follow, please!)

Quick navigation:

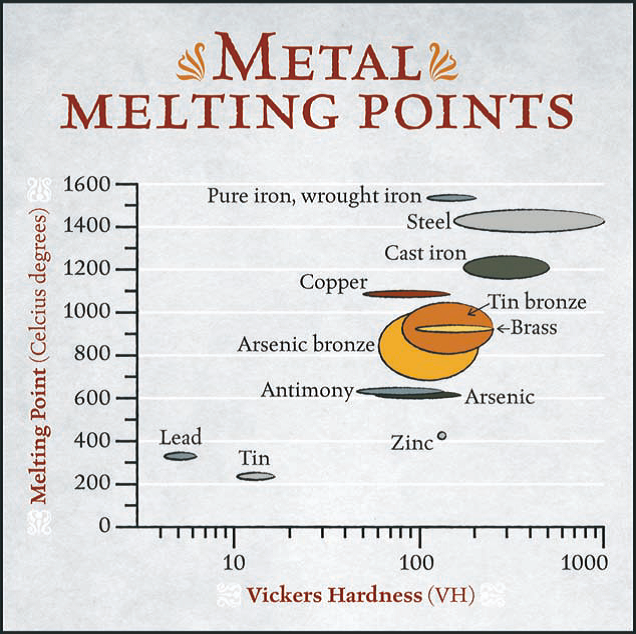

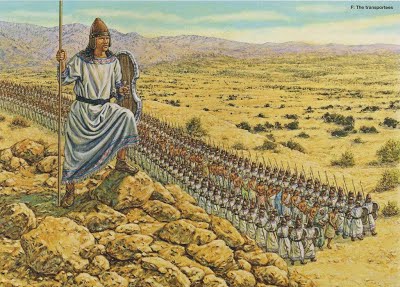

The Hittites ruled vast tracts of the Ancient Near East for over four hundred years (roughly 1650 BC - 1200 BC). Their army was feared far and wide. Their mighty infantry and thundering chariots were the dread of the battlefield. At times they could muster as many as fifty thousand men. They won many, many battles for their king and their gods. What was the secret of their success? Well, popular conception has it that the Hittites possessed an extra edge over their rivals... an edge of iron. "Hold on...iron? Well, that's how the story goes: the Hittites were ahead of their time and bore 'superior' iron weapons. The Hittites' super-hard iron swords could chop through the soft-as-butter bronze swords of the Egyptians and Assyrians. They were effectively 'Bronze Age lightsabers', making the Hittites nigh-on invincible on the battlefield. Wait a minute... invincible? The Hittites were good, but not that good. They won many battles and wars but they lost several too. And this notion that having iron weapons meant instant superiority over bronze-armoured foes doesn't quite sound right. Metallurgy isn't as black and white as that - good bronze is actually harder than many grades of iron. But back to the original question: did the Hittites have iron weapons or not? Oh, if only it was a yes or no answer :-) Steel yourself for what follows (including a few more terrible puns)... The irony of the Iron AgeFirstly, we must dispense with the perception that the Bronze Age was a time when everyone was using bronze for everything because iron hadn't been discovered yet, and that on the day someone did discover it, everyone threw down their bronze tools and took up the superior iron ones instead. Indeed, while our modern classification of the Bronze Age (3300 BC - 1200 BC) and the Iron Age (1200 BC - 500 BC) as two distinct and contiguous epochs serves as a tidy way to organise history, it is a huge simplification. In fact, iron was ‘known’ to the world all throughout the Bronze Age - i.e. before, during and after the time of the Hittites - a fact underpinned by plenty of epigraphic evidence. For example, Prof. Klaas Veenhof's translations of Assyrian merchant texts from 1800 BC describe the existence of an ancient iron trade ongoing alongside that of copper and tin (the ingredients for bronze). Prof. Veenhof's work also allows us to infer that iron was rare - extremely so and, as a result, hugely expensive. Indeed, evidence suggests that iron commanded a price upwards of forty times that of silver! The Iron of HeavenWhy was iron so expensive? Well, the only real source of pure iron was meteorites (well, almost-pure iron - meteorites are commonly composed of iron-nickel). To the Bronze Age kings, this was known as 'Iron of Heaven' because it fell from the skies in streaks of light. It must have seemed magical to the ancients - because of the way it descended from the skies and for its magnetic properties. Bronze Age kings preferred their thrones to be decorated with this heavenly iron. Indeed, any objects crafted from this divine material were highly sought-after - as evidenced by this letter from the Hittite King Hattusilis III r. 1267 BC - 1237 BC (our hero Hattu in Empires of Bronze) in response to a plea from an Assyrian King seeking an iron gift: "In the matter of the good iron about which you wrote, good iron is not at present available in my storehouse in Kizzuwadna. I have already told you that this is a bad time for producing iron. They will be producing good iron, but they won't have finished yet. I shall send it to you when they have finished. At present I am sending you an iron dagger-blade." An interesting exchange, especially the part about iron daggers. From this we know that the blacksmiths of the Bronze Age - individuals revered and respected like high priests for their skills in this strange craft - were capable of working pure iron to fashion weapons. But given the scarcity of meteorites, a Bronze Age king would have been lucky to possess just a few such weapons - not quite enough to arm the fifty thousand Hittite soldiers! Also, as mentioned above, iron weapons are not automatically 'superior' to bronze ones. They can be, if produced well, but they can just as easily be softer than bronze or too brittle to use in combat - not at all the Bronze Age lightsabers of myth. How can iron be rare? It's everywhere!But hold on, how can iron be rare? Yes, meteorites are rare, but iron comes in another far more abundant form - ore. Iron ore is everywhere. Roughly 35% of the earth's mass is iron. You can walk through any field or dig any garden and find chunks of iron ore or ironstone. Many of our hills and mountains are lined with ore too. And it was the same back in the Bronze Age: 99.99% of the Earth's surface iron was held captive inside rocky ore. Bronze Age texts don't use the word 'ore', but they sometimes talk of a 'White Iron' - looking at the photo, below, I can't help but wonder if this was their name for ore? So why didn't the Hitittes use ore to furnish their armies with iron weapons and armour? Well, they very probaby did work or at least experiment with ore. Of the many tablets found in excavations of Hittite sites, a number detail the whereabouts of ore-rich hills near their cities, so they clearly considered it of value. But working with ore would have been tricky. The problem with ore is separating the pure iron from the rock and minerals. To extract the iron, it needs to be smelted out. This involves heating up the ore until the metal softens and the chemical compounds around it begin to break apart. So how might the Bronze Age blacksmiths have achieved this? The charcoal bloomeryThe dominant metallurgical device of the Bronze Age was the charcoal fire pit, or 'bloomery'. This consisted of a cupola-shaped pit, filled with charcoal and wood. Pits such as these were more than adequate for achieving temperatures high enough to fully smelt copper and tin - the components of bronze. But to smelt iron? Not so easy. A bloomery could only reach temperatures high enough to turn iron ore into 'bloom' - a porous, spongey chunk of slag (the waste matter of stone and other impurities) and iron. A skilful Bronze Age smith might well have worked out that by repeatedly reheating this bloom to gradually melt away the slag, and laboriously hammering the product in-between heatings in order to drive out the impurities, a close-to-pure iron known as 'wrought iron' could result - broadly comparable with bronze in terms of hardness, but again, not the 'lightsabers' of legend. The starting point for producing higher quality iron, stronger than bronze, is to fully smelt the iron from the ore. To do this, much more heat is required... The blast furnaceThe 'blast' in 'blast furnace' refers to the combustion air being 'forced' or supplied above atmospheric pressure. At the dawn of iron-working, the earliest of these blast furnaces would have been unrecognisable compared to the modern-day behemoths, although the principles would have been the same: a blast furnace would have utilised bellows and chimneys to achieve much higher temperatures than charcoal bloomeries - hot enough to truly smelt iron and release it from ore. Scholars are extremely doubtful that furnace technology was discovered during the time of the Hittites. The argument goes that if the secret of ore-smelting had been 'cracked' by the Hittites, why is there no artifactual evidence? No Bronze-Age era smelting furnace has been found in the ancient Near East (the oldest surviving iron-smelting furnace dates from around 500 BC and was found in the Austrian Alps) and there is an absence even of the indelible, telltale environmental markers which one would expect to find nearby any long-lost blast complex - such as slag heaps. But as the saying goes: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Why would the Hittites have taken the trouble to catalogue the location of the ore-rich hills near their cities if ore was not of some interest to them? And let's glance again at the ancient letter from the Hittite king: "In the matter of the good iron about which you wrote, good iron is not at present available in my storehouse in Kizzuwadna. I have already told you that this is a bad time for producing iron. They will be producing good iron, but they won't have finished yet. I shall send it to you when they have finished. At present I am sending you an iron dagger-blade." What was this 'Good Iron'? It sounds like it was of a higher standard than the interim-offered dagger blade, but in what respects? Well here's the theory: could this 'Good Iron' have been the earliest outputs of Iron Age technological breakthroughs? Ultra-pure iron properly smelted from plentiful ore? Worked to be harder than bronze yet not brittle? The very first instances of steel production, even? So... Bronze Age lightsabers?So can we answer the original question about the Hittites - did they have these 'Bronze Age lightsabers' or not? There is only one thing we can say with any certainty: the Hittites certainly never had an army equipped throughout with iron weapons that were of some magical strength. But the likelihood is that:

Even if they did achieve some form of proto-steel, it all happened too late to equip their regiments against the storm that was to come: a storm that blew the Hittite Empire and many other great powers into the dusts of history in a calamitous period known as the Bronze Age Collapse. From the ashes - post 1200 BC - new civilisations gradually arose and iron-working with them. Were the Hittites responsible for triggering this shift before their demise? Well, just as many believe that the Renaissance was catalysed by the westwards flight of scholars from Constantinople (when they realised it was doomed to fall to the Ottoman Turks) in 1453, perhaps when the Hittite blacksmiths fled their old Anatolian cities during the death throes of the Bronze Age, they may just have taken the recently-discovered secrets of their craft with them into the wider world... Hope you enjoyed the read! Let me know what you think - leave a comment below or get in touch, I'd be delighted to hear from you. And if you fancy a good read set in the Bronze Age, why not grab a copy of Empires of Bronze: Son of Ishtar?

The Hittite Empire dominated ancient Anatolia for over five centuries. If a neighbouring kingdom attacked, the Hittites crushed the offending state and made them vassals. When the great contemporary empires of Egypt or Assyria encroached, the Hittites called upon their mighty army and the subjugated vassals and marched to war - usually sending Pharaoh or the Kings of Ashur home, humbled. But there was one danger that came not in the form of a rival empire or a plucky kingdom. This threat was constant and simply could not be crushed or envassalled. The Kaskans - also known as the Kaska, Gagsa and Kaskia - were a Bronze Age people indigenous to northern Turkey. Hardy and ferocious, they lived in the Pontic Mountains (or 'The Soaring Mountains' in Empires of Bronze), a long and rocky sierra overlooking the Hittite heartlands. They had no king as such, but they were populous and grouped in twelve tribes (possibly more), each living in a ramshackle wooden settlement where they alternated between farming pigs and descending into the Hittite lands to rob, raze and loot. Whenever the Hittite Labarna tried to tackle them, they would melt away into their mountain retreats again. Then, when the Labarna and his imperial armies were absent on campaigns far from the heartlands, they would raid across Hittite lands all over again. Around 1400 BC, the Kaskans descended from their mountain homes and overran the Hittite territories lying north of the range, all the way to the Upper Sea (modern Black Sea) coast, toppling the sacred Hittite cities of Nerik, Zalpa and Hakmis along the way. With that northern land lost, the Hittite Kings built a chain of forts and towers along the mountain range's southern edge to contain this Kaskan uprising. Yet it was only partially effective - Kaskan raiding parties broke through the defences multiple times, bringing fire and fury upon the Hittite heartlands.

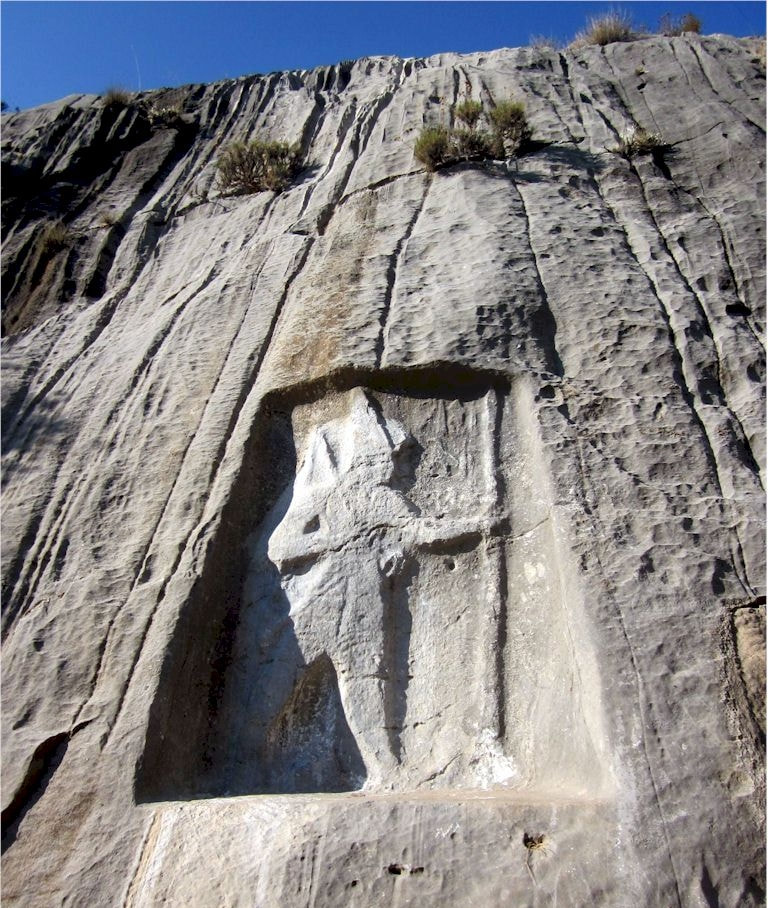

Small-medium scale raids were doubtless costly and troubling, but on the rare occasions when the many Kaskan tribes set aside their rivalries and united against the Hittites - along with support from nearby Hayasa-Azzi and Isuwa peoples - the threat became critical. Indeed, on more than one occasion, these northern hordes swept southwards, all the way to the Hittite capital of Hattusa, burning the city to the ground. More than once the Hittite throne had to be relocated further the south for fear of the Kaskan threat. Over the years of constant struggle, the Hittites learned that the Kaskans would never be conquered. However, around 1300 BC, Hattusilis III (our Prince Hattu in Empires of Bronze) did manage to reclaim the 'lost north', and also pioneered the enlistment of Kaskan troops into the Hittite Army - something that must have helped relations between the two peoples. Still, it must have been a truly tense co-existence, I'm sure you'll agree! Thanks for reading! You can find out much more about the Kaskans and the Hitittes in Empires of Bronze: Son of Ishtar An Ancient Monument...In the 5th century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus - known as "The Father of history" - travelled to western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and ventured into an old rocky canyon known as the Karabel Pass. Here, he set eyes upon an ancient relief carved into the rock high up on pass-side. It depicted a male warrior with a bow, spear and curved sword, crowned with a peaked helm. ‘With my own shoulders, I won this land,’ reads the inscription below the relief. Herodotus was perplexed for a time: the strange warrior did not look familiar to his well-travelled eye. Eventually, he came to the unsatisfying conclusion that this was an Egyptian creation – carved by a conquering Pharaoh who had marched from the Nile, around the Levant, across Anatolia and all the way to the Aegean coast. Now there were probably plenty of Pharaohs who would have been rather chuffed to have won such far-flung lands... but here's the thing: now we know for sure that it was not Egyptian. It was crafted by a people lost to history for some seven hundred years by Herodotus' time; a people who would remain forgotten for another two millennia afterwards - the Hittites. Until the early 20th century, we thought of the Hittites as nothing more than a peripheral and insignificant hill tribe living near the biblical Israelites of Canaan. Nobody realised that before this, during the late Bronze Age, they had in fact once been a colossal state, ruling all Anatolia and northern Syria as one of the ancient world's superpowers. How could such knowledge be lost? Well, the Bronze Age Collapse, as it is known, is thought to have been catastrophic, and only fragmentary evidence remains from that long-ago era. This cataclysm tore down the Hittite Empire amongst several other great powers, and changed the world forever. It is under the dust and rubble of this collapse that memories of the Hittites were buried, evidently lost to Herodotus and men of his era. In more recent history, the Ottoman Sultans sadly chose to ignore the rich history of Anatolia which pre-dated their reign. Thus, the wonders that had gone before were left buried, and the land itself was largely closed to curious archaeologists. Strange Ruins...It was only in the later days of the Ottoman regime that Turkey was opened up to the world. The French archaeologist-adventurer Charles Texier was one of the earliest modern explorers to take advantage of this by venturing across Anatolia’s central plateau. He was searching for the Roman city of Tavium, and so he began to ask the rural folk if there were any ruins nearby that had not been investigated. But the locals instead insisted on telling him about some mysterious ruins in the high, rugged lands east of Ankara - ruins that were not Roman or Greek... but much, much older. Intrigued, he set off at once. Upon his arrival, he stopped, confounded, enchanted, his eyes transfixed upon the foundations of a colossal stone city in that bleak, lonely wilderness. The ancient ruins were decorated with more carvings of strange gods and people in that same odd-looking garb from the Karabel Pass relief. But he realised that this was not Egyptian, nor Assyrian, certainly not Roman or Greek. Within the ruins, he found fragments of a hitherto unknown style of cuneiform writing. Little did he know it at the time, but he had just stumbled upon one of the greatest discoveries of his time, for this was Hattusa, capital of the lost Hittite Empire. Unearthing the Truth...Texier's 'discovery' was ground-breaking, but there was still a long way to go before these ruins and the wonders buried underneath could be investigated, interpreted and understood. Here's how it all played out:

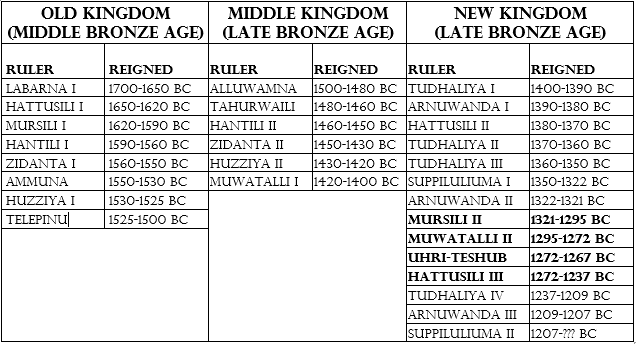

Thanks to men like Texier, Sayce, Winckler, Hrozny and their modern counterparts Blasweiler, Bryce and many more, the Hittites are forgotten no more! Want to know more about the Hittites? Read all about them in Empires of Bronze: Son of Ishtar The Hittites (pronounced hit-tights): a civilization forgotten to history for so long. So who were they? Where do I begin - in their Bronze Age heyday, perhaps? Or... how's about 1986 and in my living room... I was eight years old and watching ‘Ghostbusters’ - a firm childhood favourite of mine - on VHS. During the movie, Dan Aykroyd claims that the Hittites lived six thousand years ago and worshipped a god named Zuul. I now know that every word of this is utter cobblers. Needless to say, I hope Mr. Aykroyd feels suitably ashamed, both for being historically inaccurate and for wrecking my childhood. A few years later in Religious Education classes at school I was taught that the Hittites were a small, insignificant Canaanite tribal people that had lived in the hills of biblical-era Palestine around 900 BC. These days I know that while there were highland tribes known as 'The Hittites' in that region at that time, they were but a thin diaspora - the last whispers of a great lion’s roar that had gone before... Because, from 1600 BC all the way through to the catastrophic collapse of the Bronze Age around 1200 BC, the Hittites were not a petty hill tribe but a mighty superpower. They dominated most of modern Turkey and northern Syria, possessed a feared military and controlled a ring of vassal states - most notably Troy. They were the rivals of Egypt and Assyria, and a towering presence from whose shade Homer's Greeks must have looked on enviously. Now I must admit that I first began to grasp the sheer scale of the Hittite civilisation via the most nonacademic of mediums: in my late teens (when I should have been studying for university exams), I played the game, ‘Age of Empires’, to death. In it I controlled the Hittite civilisation in its pomp, raging across the Ancient Near East and obliterating Assyrian and Egyptian armies. Not sure why I felt the need to confess this - I just think the game deserves an honourable mention :) Watching Ghostbusters hundreds of times, trying not to fall asleep in RE classes and playing computer games probably wasn’t the way to study history, and so the Hittite question remained largely unanswered. Yes, by my uni days I had come to understand that they had been a world superpower. But what did that world of their look like? Their cities, their road, their armies? The lives of individuals - the fears and hopes of the common and the high-born? What did they eat? How did they celebrate? And my usual favourite - what was their most vulgar swear word? Following university, I trundled through several 'day job' years with not a lot of time for reading history. It was only when I made the transition from day job to writer, I realised that - at last - I had the opportunity to don my time traveller's hat and explore the Hittites and their Bronze Age world in full! The expedition began in earnest on an atypical, sweltering Scottish June afternoon. I packed a bag with a newly acquired book – Trevor Bryce’s ‘The Kingdom of the Hittites’ – a sandwich and a bottle of cold juice, then took leave of my writing study and set off to the green banks of Tamfourhill (an old Roman site on the Antonine Wall, overlooking the modern Forth & Clyde Canal). I parked myself in the shade under a spreading oak, checked there were no evil spiders hovering about above or behind me, then began to read... “The Near East in the Late Bronze Age is a complex picture of constantly shifting balances of power amongst the major kingdoms of the region, or expanding and contracting spheres of influence, of rapidly changing allegiances and alliances as Great Kings vied with one another for supremacy over their neighbours. Within this context the kingdom of the Hittites emerged, struggled for survival, triumphed, and fell. ” The hooks were in! Shivers raced across my skin and hours passed as this long lost world came alive in my mind's eye. I was falling back through the centuries as I read. Forgotten ruins were thrown up, broken walls towering once more. Long dead oracles and priests rose from the mists of eternity to drone strange chants. Colossal armies emerged from the dust to march again. Great Kings shed their tombs to take seat upon their iron* thrones once more. I could smell the barley beer they drank, taste the baked bread, hear the songs rising from the temples, feel the heat of the Anatolian sun and see the glow of the bronzesmith's crucible. Every sense was engaged, at last. That initial question ‘Who were the Hittites?’ spawned a thousand more (as all good questions do), and so on I went, collecting more texts and papers, scouring the Web, making friends with helpful scholars across the world. Now the Hittite world is not one of shadow. It is golden, enchanting, strange and severe. *Iron thrones, in the Bronze Age? What?! Yes, it's true: Bronze Age civilizations had not yet worked out how to smelt iron from abundant ore. But they did have precious amounts of it in the form of meteorites, or 'Iron of Heaven' as they called it. What little meteorite iron they did have was used for ceremonial purposes, including the decoration of thrones. But... some say the Hittites were the first to crack the secrets of ore smelting, unlocking a wealth of iron with which they could equip their armies! This opens a delicious and different can of tangential worms, which I will delve into more deeply in a future article. Tangents aside, here are the key things you need to know about the Hittites (and I'm only scratching the surface here): Where was the Hittite Empire?In the Bronze Age, the Near East was the hub of the world. Four great powers held sway in this region: Egypt, Assyria, Ahhiyawa (Homer’s Achaean Greece)… and the Hittites! The Hittite Empire centred on the heartlands of mid-Anatolia (modern Turkey). Their choice of this terrain drew sneers from their rivals - for in comparison to the fertile lands of the Nile and Assyrian Mesopotamia, it was a rocky, barren and windswept upland, far from the trade roads. Outwith the heartlands lay a ring of vassal states – Wilusa (with its capital, Troy), Arzawa, Lukka, Pala, Tarhuntassa, the Seha River Land and more. In Syria, the Hittites also held sway with a pair of crucial bulwark viceroyalties, Gargamis and Halpa (Aleppo), and more loyal vassal kingdoms such as the trade-capital of Ugarit, Amurru and the desert lands of Nuhashi. The city of Hattusa was the Hittite capital, situated around one hundred miles east of modern Turkey's capital, Ankara. It was built upon a rocky mountainside some 1,200 meters (nearly 4,000 feet) above sea level. Reconstructions and remains show that the Hittites were fine architects and that they understood thoroughly the art of fortification. When did the Hittites rule?The Hittite Empire spanned the Middle and Late Bronze Age. It rose sometime in the 17th century BC and crumbled as the Bronze Age itself came to a catastrophic end in the late 13th and 12th centuries BC (in other words, 1600-ish-1200-ish). Historians now recognise three distinct periods within this timespan: an embryonic Hittite ‘Old Kingdom’, a period of decline known as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ and an era of resurgence, apogee and the abrupt end known as the ‘New Kingdom’. What does 'Hittite' mean?This is a tricky one to answer - so bear with me! Essentially, it is something of an etymological anachronism - similar to the way we refer to the 'Byzantine Empire', when in fact the people of 'Byzantium' considered themselves Romans and part of the Roman Empire. With the Hittites, it all stems from the Christian Bible and the Hebrew Tanakh. The Tanakh refers to the aforementioned biblical hill tribes of the 9th century B.C. as the enemies of the Israelites and of God. The Book of Genesis, Chapter 10, described these same people as the descendants of Noah, through Ham, then Canaan, and then Heth (so 'Hethites', or 'Hittites'). This post-hoc label has stuck, even though the 'Hittites' themselves - of biblical times and the earlier imperial age, would not have called themselves this. We suspect they might have identified themselves as 'The People of the Land of Hatti', or 'The Nesili' (the people who speak the Nesite language). Of course, for the purposes of sharp storytelling and accessible research, I and almost every single other author of fiction and fact stick to the concise term 'Hittites'. EthnicityThe Hittites were an ethnically diverse people. It was the Hatti – the native inhabitants of central Anatolia – who inhabited the heartlands initially. Then, sometime in the 3rd or early 2nd millenium BC, Indo-Europeans migrated there and supplanted the Hatti as the ruling class. Added to that there were others of native Anatolian stock (Hurrians and other nearby tribes) and Assyrians (thanks to years of trading and collaboration between Assyrian and proto-Hittite peoples). It was the personality-cult of the Hittite King and the ethos of religious inclusiveness which helped bind these people together to forge a common Hittite identity and culture. Culture & ReligionThis was the era of the temple-culture, where civilizations sprung up around great monuments and divine sanctuaries near which they farmed and herded and within which they paid tribute to their gods. The word of their gods and kings was absolute. The Hittite Empire epitomised this in its own peculiar, ascetic way. Every Hittite city across the heartlands sported several temples dedicated to their gods and the Great Storm Temple at Hattusa was the religious centre of the empire. They celebrated harvests and spring rains feverishly with dancers, acrobats and wrestlers leaping to and fro, priests and oracles singing and soldiers performing parade drills. Men and women would carry a bright train of cloth fashioned to look like Illuyanka the evil mythical serpent in a re-enactment of his battle with Tarhunda the Storm God. All while the people watched on, singing and clapping, feasting and drinking foaming pots of barley beer. The Hittite Empire was known as ‘The Land of a Thousand Gods’, and it’s easy to see why (in fact, the title is probably an understatement!). Their system of deities is perplexing, non-linear and unfamiliar to the modern theological eye. It seems that their chief deities were Tarhunda the Storm God and his spouse Arinniti, Goddess of the Sun. That said, each major city had a storm god, a sun goddess or some specific deity of its own, rapidly expanding the godly ranks. More, the Hittites were not just polytheistic but pantheistic too: they worshipped the ether around them, believing every spring, tree, rock and meadow possessed a spirit. They not only observed absolute religious tolerance but also practiced syncretisation, the custom of integrating foreign gods into their own pantheon. So no schisms and no theological in-fighting (can you imagine!). As mentioned above, this harmony and inclusiveness was surely one reason why the diverse peoples of the Hittite realm shared a common identity. As well as many priests and priestesses, the Hittites also employed diviners, snake and bird-watching oracles, and ‘Old Women’ – aged females who would perform religious and semi-‘magical’ rituals, such as:

Rule, Government & LawThe Hittite empire was ruled by the 'Labarna' - the high king, who would be addressed by his subjects as 'My Sun', and was considered as the direct appointee of the Gods. He also served as high priest of the empire and each year he would travel extensively to preside at festivals in the outlying cities. These personal appearances also helped forge a degree of imperial identity and belonging amongst his diverse subjects. The Labarna's word was absolute, and he was protected at all times by the Mesedi, an elite corps of royal bodyguards. However, many times throughout the centuries the Labarna was challenged and overthrown - usually murdered - by rivals. In terms of territorial government, the Hittite Empire employed a tight control over its 'heartlands' and a loose hegemonic system of control over the neighbouring vassal regions. These vassals weren't subject to Hittite taxes as such, but they were required to visit the Labarna once a year to deliver a tribute of sorts (horses, crop, treasures, ingots of metal or the like). This served to renew their oath of fealty to the Hittite throne. In return, the vassals were granted military protection and favourable trading status. At regular intervals throughout the rest of the year, the Labarna and his Panku - a council of nobles - would sit in session to discuss matters of supply, state and war. Regarding law, we know from the tablets excavated at Hattusa that the Hittites favoured financial penalty over death or mutilation. Also, slaves had rights and could work their way to freedom (not just rely on a benevolent master to free them). In general, they tried to build a self-policing society and they had a legal code, largely built on precedent, e.g.:

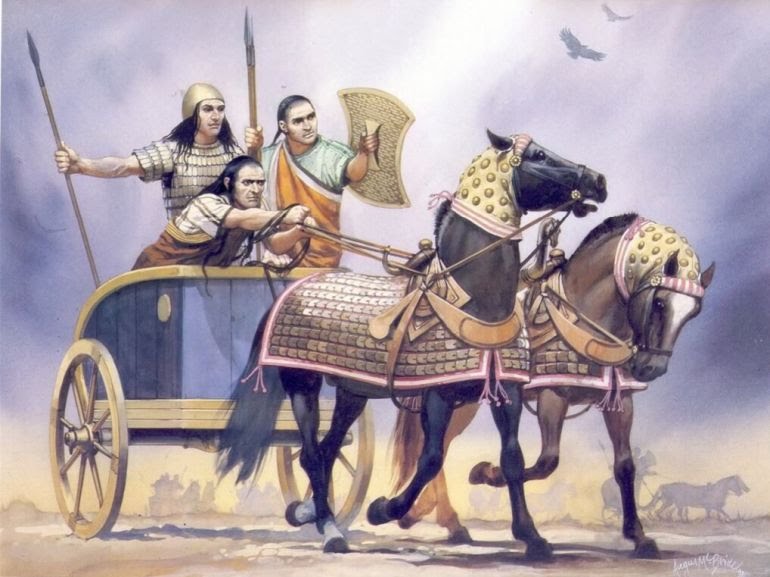

They also had some rather wacky and quite upsetting laws: bestiality was punishable by death... unless it was with a horse. And if you served up unclean food for the king or the gods, you’d be forced to eat an unclean meal as punishment – a heaped plate of steaming human excrement and a pint of pee to wash it down. Sorry if this is a lunchtime read for you... MilitaryThe Hittite King most-likely controlled 10,000-20,000 'native' troops. In times of major conflict, the Labarna could also levy armies from his network of vassals to supplement his core regiments. When gathered en-masse, the Labarna's forces would have been a match for any of the contemporary powers. The infantry were armed with spears, axes, curved short swords, powerful recurve bows and bronze-tipped arrows. They used rectangular or hourglass shields and wore bronze or leather conical helmets. The infantry were likely most useful in rugged ground or in forested regions, where they could rove towards and pin down bandits or invading armies. But when it came to flat, open ground, they would most likely serve more as a pivot for the chariots - the tanks of the Bronze Age! It seems that there was a military academy somewhere close to Hattusa, where young Hittite men were drilled mercilessly to become soldiers, and where horses brought in from the plains of Troy and Lukka were broken and trained to tow the war chariots. In Son of Ishtar I name this military school 'The Fields of Bronze'. So much moreThere is so much more I could go into: The land - a diverse geography of expansive grassy plains, mountains, coastal regions, river valleys, and desert. The economy - based mainly on grain, textiles, shepherding, and their expertise in metalworking. The language: they spoke Nesite, an Indo-European language, but communicated with foreign powers using Akkadian - the Bronze Age ambassador's language of choice. And when Hittite words were committed to clay tablets, it was in Cuneiform A Script – a writing system of wedges and dashes. But I think that's enough for now.

Oh, actually - one more thing: their most vulgar swear word? Easy, it's hurkeler - meaning 'one who indulges in deviant sexual practices with animals'. Sorry! :-) Fancy hurtling back through time and having an adventure in the Hittite era? Well funnily enough, you can, with the first book of my Bronze Age series Empires of Bronze: Son of Ishtar

Here's the back cover text to whet your appetite: "Four sons. One throne. A world on the precipice. Sounds good? Why not grab a copy? Empires of Bronze: Son of Ishtar is available in eBook, paperback and audiobook formats.

|

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed