|

On 9th August 378 AD, under a blistering-hot Thracian sun, two-thirds of the Eastern Roman Army was slaughtered. Emperor Valens fell along with his legions. It was the day of the Goths... it was the Battle of Adrianople.

The time-period has had me in its talons for nearly a decade. The Legionary series is entrenched in the brutal chain of events of those times: the coming of the Huns, the flight of the great Gothic tribes into Roman territory and the colossal upheaval and destruction that ensued in what was known as ‘the Gothic War’. The Battle of Adrianople was one of the bloodiest encounters of that savage conflict, and one that remains surrounded by unanswered questions and misconceptions. So when I had the chance to visit the ancient Roman city of Adrianople (modern Edirne in northwest Turkey) and explore the countryside nearby where the clash is thought to have occurred, I set my mind to exploring and investigating in an attempt to answer what is probably the battle's greatest riddle: where exactly did it occur? That's right, we still don't know. Anything between 20,000-80,000 men died on that fateful day. Legionary bodies, banners, helms, swords, spears, shields and Gothic equivalents would have been strewn all across the blood-soaked soil. Most of this would have been cleared away or scavenged in the immediate aftermath, but surely a great deal of it must remain where it fell. Somewhere outside Edirne, there must be a wealth of archaeological remains, fixed forever underneath the modern topsoil. Yet there has never been a positive identification of the battle site. There have, however, been two main candidate locations proposed by modern historians. So, armed with a camera, chewing gum, a hire car totally unsuited to the mud-track roads (white and shiny when we picked it up, mud-brown with bald tyres when we returned it) and a very understanding wife, I set about exploring these two sites. The first part of this blog is a narrative of the Gothic War and the battle itself, which should help provide a frame of reference for my findings, further down the page. I have to stress that I am merely an amateur historian – but an obsessively enthusiastic one nonetheless. I expect some readers may appreciate the concise nature of my investigation, others may feel I am not delving deeply into certain aspects, but I hope all can enjoy the journey with me. Finally, beware that this discussion contains some spoilers to the fifth book in the Legionary series – Gods & Emperors… I’ve heard it’s a must-read ;) Part 1: The Road to War

So why did the Romans and the Goths meet in battle on that fateful day? One man - a contemporary of the brave legionaries and Goths who died on the plains of Thracia - is best placed to explain...

A Voice from History

There are many fine books discussing the Gothic War and the Battle of Adrianople, but all of them draw from one primary source: Ammianus Marcellinus’ ‘Roman History’, written in or before 391 AD, is a gold mine but a labyrinthine one that delivers as many dead ends as it does precious finds. Detail is rich one moment then fleeting the next, and putting shape to times, places, and events is a bit like nailing jelly/garum to a tree. Ammianus was a military man but this is not a strictly military chronicle, which perhaps explains the patchiness of his accounts in places. Another explanation is the suspicion that Ammianus is not thought to have been an eye witness to the battle, but is likely to have visited Thracia after the Gothic Wars to assess and understand the events (I wonder if he hired a pristine, white wagon and handed it back in a muddy mess to a raging trader?).

I should point out that I am not fluent in Latin, so I rely upon the translations of Ammianus and subsequent investigative work performed by many esteemed historians including N.J.E. Austin, Hans Delbruck, Peter Donnelly, Ian Hughes, Noel Lenski, Simon MacDowall, F. Runkel and Herwig Wolfram amongst others. Thracia: a Land in Turmoil

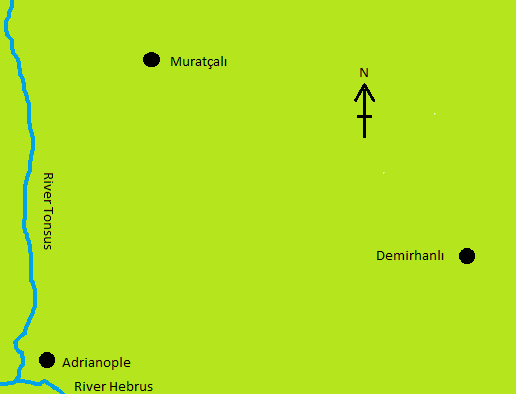

Ammianus describes how the Roman Diocese of Thracia bore the brunt of the Gothic War. This land is well-trodden by the legionaries of the XI Claudia in my Legionary series, and here’s a map of that region with some of the key locations mentioned in this blog:

Timeline of Events Leading up to the Battle of Adrianople

376 AD

...the day of reckoning has arrived. Part 2: The Battle - 9th August 378 ADNumbers

Size estimates of the opposing forces’ vary, some arguing that each side fielded around fifteen thousand men, others claim it was more than sixty thousand warriors each. Most agree, however, that numbers would have been equal, or that maybe the Romans would have enjoyed a slight advantage. I discuss the legions of this era a little more, here and here.

Phases of Battle

The Battlefield

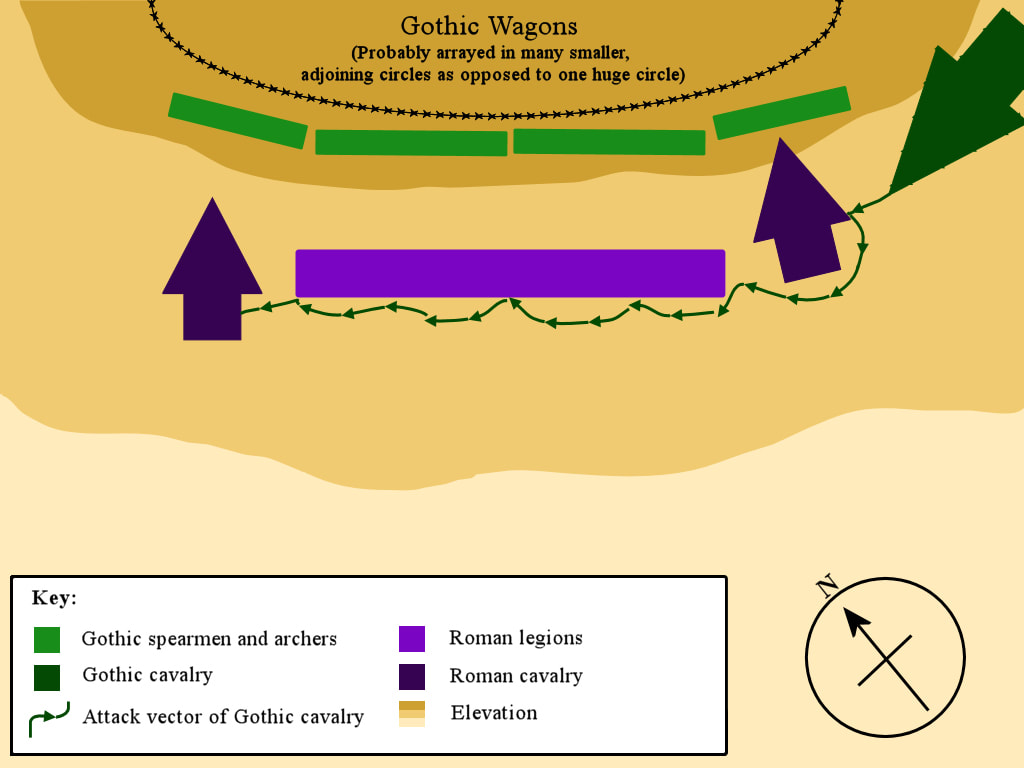

Based on the phases (above), the battle is likely to have taken shape as in the following illustration, with the decisive arrival of the Gothic cavalry happening at phase 4.

Aftermath

With the Eastern Roman Army in ruins, Thracia was Fritigern’s in all but name. The 9th August 378 AD was supposed to be the day the Gothic War was won; instead, it became a black stain on Roman history, it ensured the Gothic War continued and – longer-term – gave rise to the Gothic confederation known as the Visigoths, who would one day sack Rome itself.

Some say the battle marked the end of the era of infantry dominance on the battlefield, but this is an exaggeration. Yes, this was the last time Rome's legions resembled anything like those of better days, but the forces that met outside Adrianople were primarily composed of infantry. From the late 4th century onwards, cavalry certainly grew ‘heavier’ but infantry still dominated armies, numerically at least, with an infantry:cavalry ratio of 3:1 or 4:1 commonplace well into late Byzantine times. Part 3: Searching for the Battle Site

So where did this great clash occur? Well, let’s examine what evidence we have:

On the morning of the 9th August 378 AD, Valens and his army marched in a merciless heat (August temperatures regularly reach 40 °C in this part of the world). Ammianus states: “So after hastening a long distance over rough ground, while the hot day was advancing toward noon, finally at the eighth hour they saw the wagons of the enemy.” This translation implies that the Romans had marched for eight hours, or as other translations have it to the eighth milestone outside the city, when they spotted the Gothic wagon laagers formed up in the distance. A later work, the Consularia Constantinopolitana, claims that the battle occurred twelve miles from Adrianople. So a rough radius of 10-12 miles seems to be a fair range within which to locate the battle site. Ammianus also indicates where Fritigern halted his horde in reference to other, known locations: “The barbarians… arrived within fifteen miles from the station of Nike, which was the aim of their march… when the emperor… resolved on attacking them.” Our historian also states that Fritigern and his horde halted three days after something. What that ‘something’ is remains unclear, but Donnelly argues convincingly that it refers to the Goths’ arrival at the southern end of the Tonsus valley. If this was the case, then we are looking for a site roughly three days’ march (at the lumbering pace a horde would move) from the southern end of the Tonsus valley, towards the Nike waystation. However, this wouldn’t be a direct route as such a path would take them past and dangerously close to Adrianople. So, this means we are looking for somewhere located:

Added to that, we are looking for a spot with attributes which would have convinced Fritigern to halt his horde, i.e. somewhere:

And finally, given the pivotal moment in the battle occurred when the Greuthingi cavalry unexpectedly appeared, we have to ask how the terrain itself might allow for that. So, our last criterion is that the site should:

The Candidate Sites

Two sites in the 10-12 mile zone have been identified and long debated. MacDowall and Potter point to the ridge immediately south of Muratçalı (a farming village north of Edirne/Adrianople), while Donnelly, Runkel and Lenski insist the dominant ridge at Demirhanlı (another village northeast of Edirne) is the one. So, with the criteria outlined above, I visited each location.

Site 1 - Muratçalı

We drove north from Edirne, passing through the farming village of Boyuk Doluk – rumoured to be the site of the farmhouse where Emperor Valens retreated to after the battle, wounded, and then died. Upon exiting this village we saw, as MacDowall stated we would, the dominant ridge that rests a mile or so further north:

Next, we made our way up onto the ridge. It was incredibly still and utterly silent given how high and exposed we were. I must admit it was a rather poignant moment for me, bringing a touch of reality to the legend I’ve spent the last decade writing about:

The ridge levels out onto a large-ish plateau. This photo is taken from the northern end/back of the plateau, looking south along the flat area (the point where road meets sky is where I was standing in the previous photo). While Fritigern's warriors would have been arrayed along the distant edge of the plateau, facing south, the rest of the families, tents and animals would have been encamped on this stretch of ground.

So, how did Muratçalı fit the criteria for the battle site?

Located roughly ten to twelve miles north/northeast of Adrianople?

Site 2 - Demirhanli

After a somewhat comedy navigational malfunction (involving the satnav on/off button falling off and the thing packing in), we spent the next few hours traversing quagmires and hair-whiteningly narrow dirt causeways with tarns/pools on either side but finally found our way back to Edirne. Topping up the car with diesel and our bellies with juicy lamb kebabs, we then set out to the east – presumably the route of a Roman march from Edirne to the Demirhanlı site. We crossed a series of small rises along the way, yet these were but false summits, because after about ten miles, we came over one gentle hill and sighted Demirhanlı, a small town perched on the edge of another formidable ridge.

So overall, how did Demirhanli fit the bill as a potential site for the Battle of Adrianople?

Located roughly ten to twelve miles north/northeast of Adrianople?

Driving up through Demirhanlı, I noticed that this 'ridge' was in fact more like a shelf - the land behind it remained at a similar elevation for many miles.

Conclusion

As you can see from my findings above it’s hard to identify one clear candidate. Emotionally, I connected with the Muratçalı site more readily – perhaps because it was the first of the two I visited, and perhaps because I only recently read up on the Demirhanlı theory. But looking at it rationally, we have two flawed candidates. The paltry distance between the Tonsus and the Muratçalı site doesn’t make sense when you consider the sound argument that the Goths had been on the move for three days since leaving the Tonsus valley. Equally, the water source west of Demirhanlı weakens this site’s merits (as does its over-closeness to Nike). I have to reiterate that we are not dealing with an exact science here: the criteria of water sources, location relative to Nike etc are all based on the many educated but varying and sometimes contradictory Ammianus translations. Shifting sands, eh?

So how do we root out a definitive answer? Well, investigation using the latest imaging techniques and metal-detecting would seem like a logical next step (and certainly a step up from an inquisitive chap with muddy shoes, a muddy car, a camera and an over-active imagination). Muratçalı and Demirhanlı could be swiftly ruled out or hailed as the true site, or perhaps another site might come to light. Given the ambiguity of the eight hour/eighth milestone thing – perhaps the scope of exploration should be widened? But such ventures aren't on the cards as things stand. The Turkish people seem to underplay their magnificent Byzantine and Roman heritage, while funding and permissions remain a constant barrier to an in-depth search. And that is such a shame, because there is a treasure out there, waiting to be discovered. In any case - and you can call this cheesy or overly poetic if you like - I certainly found my treasure out there. I hope you enjoyed the pics and musings. If you fancy having a look at my time in Istanbul as part of the same research trip, you can do so here. And, of course, if you fancy reliving the fraught lives of the legionaries in the time of the Battle of Adrianople...you can! My Legionary series will take you there!

2 Comments

Ogontion

3/8/2020 10:10:58 pm

Thank you Gordon, for all of your excellent research around this fascinating campaign. I really enjoy the background you provide and I hope that you can eventually share some of the answers to your questions. I'm now reading and very much enjoying your 2nd book of the Legionary series.

Reply

John Parry

10/7/2021 12:21:43 pm

Really interesting piece. Thank you. It is the first time I had considered the obvious dust cloud the Gothic cavalry must have made as they rode towards the battle.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed