|

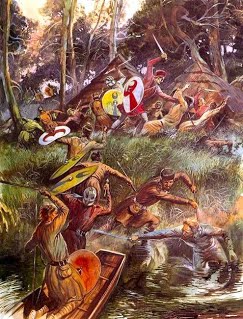

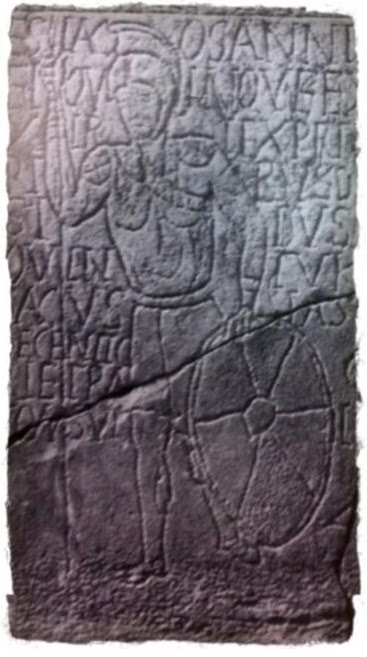

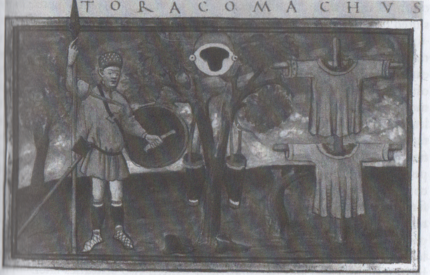

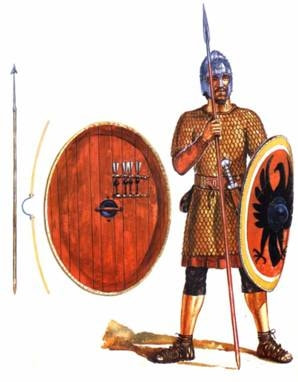

The Roman legionary: an iconic figure in military history. Ask almost anyone to describe these ancient soldiers and I’d bet you a solidus that they use the word ‘armour’. Good armour allowed the legions to dominate the battlefield, moving in tight, well-ordered formations that were the bane of many a foe. Over the centuries, the legions evolved and so did their equipment: in the Republican era they mainly wore mail; in the Principate period they developed the unmistakeable lorica segmentata. In the later empire they reverted to mail once more (and sometimes scale). But there is a curious anomaly in this progression – a nebulous notion that in the late 4th century AD, legionaries didn't bother wearing armour at all during battle. Really? Why on earth would a military superpower abandon the use of armour, something that was - and had been for centuries - one of its strengths? And why would the men serving in the legions want to face their sword, spear and bow-wielding foes wearing nothing but an itchy tunic? Well, according to Vegetius, a Roman writer from the period in question, that is exactly what they did: “…it is plain the infantry are entirely defenceless. From the foundation of the city till the reign of the Emperor Gratian, the foot wore cuirasses and helmets. But negligence and sloth having by degrees introduced a total relaxation of discipline, the soldiers began to think their armour too heavy, as they seldom put it on. They first requested leave from the Emperor to lay aside the cuirass and afterwards the helmet. In consequence of this, our troops in their engagements with the Goths were often overwhelmed with their showers of arrows.” - excerpt from De Re Militari (Latin for: "Concerning Military Matters"). Vegetius attributes this 'negligence and slothfulness' to the soldiers and later on to the imperial military system in general. For a long time, his claims were accepted: but while most went along with his view that the late legionaries did not wear armour, some insisted they did. Now, thanks to the work of modern historians, we have a greater understanding of the period and with that knowledge, we can settle the debate. So, armour or no armour? Which camp is right? Er, neither...and both! Allow me to explain. Let's take a trip back to late antiquity... A Changing WorldIn the late 4th century AD, the Huns surged across the Eurasian Steppe in incalculable numbers, hitting Eastern Europe like a storm. Their arrival shattered the centuries-old Gothic/Germanic pseudo-states north of the Danube and east of the Rhine. The worlds of the Thervingi and Greuthingi Goths, the Quadi, The Alemanni, the Franks, the Saxons and the Vandals were thrown into chaos. Millions of these tribesmen were displaced from their homes by the pillaging Huns. For most, there was only one place to run: west or south… into the empire. Thus, imperial territory was soon swamped by an inflow of foreign peoples. The Romans probably saw them as raiders intent on slaughter, while they would likely have considered themselves as refugees, fighting for their survival. It was late 376 AD when 100,000 Goths, led by Fritigern, fled like this from the Huns. Fritigern's horde spilled southwards across the River Danube and into the Roman Diocese of Thracia. The sight of them must have sent fear through the veins of every imperial subject - for the Goths had been a truculent neighbour to the empire for many years beforehand. But there was actually an air of promise about Fritigern’s arrival, for he and his people entered imperial territory under truce, wilfully entering a temporary refugee camp and agreeing to provide troops to serve in the legions in exchange for a grant of Roman farming lands within Thracia. However, things quickly turned sour when food ran short and the Roman officers began grievously mistreating the Goths. Legend has it that the Romans offered the starving Goths rotting dog meat to eat and demanded their children - to sell into slavery - in exchange. Unsurprisingly, this sparked a rebellion and the Goths broke free of their vast refugee camp. Suddenly, the thinly-garrisoned lands of Thracia had an army of enraged Goths to deal with. This was the start of the Gothic War. Fritigern led his horde well and battled hard, meeting the legions of Thracia in 377 AD at Ad Salices. It was a bloody pitched battle that lasted an entire day, but it ended in stalemate and solved nothing. After Ad Salices, both sides withdrew – the Goths to the north of Thracia and the Romans to the south – each bloodied and dazed. Perhaps it was this inconclusive and brutal clash that drove Fritigern to alter his strategy. Instead of regrouping and planning another direct clash with the legions, he based himself at the town of Kabyle with a small guard, and broke up the rest of his horde into multiple small warbands, assigning each a particular part of Thracia to rove around. Swift and lethal, these warbands made the land their own, striking at Roman wagon trains and razing towns and forts, never remaining in one place for too long. The battered and depleted Thracian legions – pinned in the well-walled cities that the Goths could not take – possessed neither the numbers nor the speed to intercept the warbands. They waited in hope for the arrival of Emperor Valens, who was rumoured to be bringing his Praesental Army (consisting of some 30,000 palace legionaries and crack cavalrymen) in relief. And Valens did arrive in Constantinople in May 378 AD, determined to end the Gothic War. Some generals within Valens’ retinue called for him to march at once from the region around Constantinople and out into Thracia. But even with his huge army, the roaming Gothic warbands still presented a conundrum: how could a lumbering, marching column of ironclad legionaries – however numerous – tackle an even more numerous enemy that was as elusive as mist and refused to offer pitched battle? Valens knew that to lead his army into the heart of a Goth-infested Thracia as a column would be like walking naked into a swarm of hornets: they might attack from any and every direction, or swing down behind his column and cut off his route back to Constantinople. He knew that Fritigern's roving warbands first had to be herded and driven back to their master at Kabyle - forged into one great horde again - before he could bring his Praesental Army to bear in a classic field battle. So, how did he set about herding many thousand of deadly Goths? He called for Sebastianus… Sebastianus was a general of the Western Empire. He answered Valens’ call immediately. Sebastianus’ nous of abstruse warfare was legendary, and the canny general swiftly demonstrated his wisdom. After reviewing the situation in Thracia, he asked Valens for just a handful of men from each Roman regiment – legionaries, archers, slingers, javelin-throwers and riders – totalling no more than a few thousand. He then instructed this heterogeneous force to shed their armour and any unnecessary burdens, before leading them out into the Goth-infested countryside. They moved not under the sun like a marching column, but at night, stealing across the land like shadows, faces blackened, wearing not a jot of iron garb to catch the moonlight. Swift and silent, Sebastianus’ force caught several of Fritigern’s warbands unawares, falling upon them hard and fast. His most famous success was in infiltrating a large Gothic camp by the River Hebrus late one night: he and his men waded up the shallows of the river to draw alongside the camp, then climbed up the riverbank and fell upon the startled Goths, slaying and scattering them and reclaiming many chests of plundered Roman coins. In these encounters, armour would have been heavy, noisy and would have blown any chance of them sneaking up on the Goths – one glint of torchlight or moonlight on iron or the 'shushing' of a mail shirt could have been the difference between success and failure… between life and death. More, the nature of combat when they engaged with the Goths like this was nothing liked pitched battle. It did not involve two lines of men advancing slowly towards one another behind a shield wall – instead, it would have been fraught, swift, often one-on-one combat. In this kind of skirmish, being spry and dexterous would have been far more advantageous to the legionaries than the swaddling protection of a mail or scale shirt. Sebastianus’ proto-guerilla campaign eventually forced Fritigern to abandon his strategy and recall his roaming warbands. With the horde reunited, it was only a matter of time before they would face Emperor Valens and his Army. And face them they did, on the 9th August 378 AD, at an as-yet-unlocated site roughly a morning’s march north of Adrianople. When the imperial legions lined up across from the Gothic horde at the infamous Battle of Adrianople, they did so… wearing armour*. Why? Because in this situation, armour was clearly advantageous. There was no call for the stealth and speed of Sebastianus' sorties, no need to move in silence or stay unseen. Now they were face-to-face with the enemy, on open ground, horns blaring and banners waving - a classic pitched battle. The Roman legions lined up in a phalanx of sorts, shoulder-to-shoulder, helms strapped on, iron vests buckled in place, shields interlocked to form an impenetrable barrier, showing the Goths just their spear tips and the fire in their eyes. Here, armoured torsos and helms on heads offered strength, weight and unity to their battle line. * Our primary source for the battle comes from the Roman historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, who states that the legionaries at Adrianople were ‘weighed down by the burden of their armour’. So there is my theory: the 4th century AD legionaries almost certainly did wear armour when engaged in pitched battle*, but shed it when they employed what we would describe as 'guerilla' tactics - something that became more and more prevalent in the twilight of antiquity (when costly field combat became a rarer occurrence too). Vegetius' claims that they wore no armour simply because they were lazy, or because the military system was crumbling, simply does not tally with the narratives of the Gothic War (chiefly that of Ammianus Marcellinus). This poses one final, additional question: why did Vegetius get it wrong? * There may well be some weight in the thinking that as time progressed, the late legions opted to dress just the front few ranks of their infantry in armour (a tactical and logistical choice); this certainly became a standard practice in later ‘Byzantine’ times. Such a notion has even been mooted regarding the iconic lorica segmenta-clad legions of the Principate. The Problem with VegetiusVegetius authored two texts: De Re Militari, and another work focused on Veterinary medicine. We don't know for sure what his occupation was, but one has to question his credentials and motivations for writing military commentaries - just as one should always question and try to understand the agenda of any historical treatise to shed a more critical light on its content (some texts can prove to be solid and dependable, while others, particularly panegyrics and polemics, can be turn out to be significantly detached from reality - Jordanes' Getica, a work produced to please an Ostrogothic king, being a prime example of the latter). Regarding Vegetius' credentials: it seems that he was chiefly a vet and secondarily a bureaucrat, but never a military man; modern historians such as Elton, Goldsworthy and MacDowall point to his accounts of 4th century AD warfare which they describe as 'somewhat stilted and confused'. They argue that it is very likely that Vegetius misunderstood the diversity of military tactics that were employed during the Gothic War. Apropos his motivation: Vegetius was something of a romanticist, lamenting the lost ways of the ‘legions of old’ (in De Re Militari, he digresses to reminisce over the manipular legions of the Republican era) without really understanding the tactical and strategic necessity of the late 4th century AD legions' art of war. This is quite possibly why he reported on Sebastianus' – very successful if unconventional – guerilla campaign as a martial nadir simply because it did not live up to his expectation of the Roman way of war. To supplement the above theory, we can look to the evidence for the use of armour before, during and after the period he denounces. For example: 1. Monumental and Epigraphic Remains2. Alternative Literary Sources of the Day The Notitia Dignitatum (Latin: "The List of Offices") lists 35 armour-producing fabricae (arms factories) and their locations in the early 5th century. The majority of these had been in existence and producing arms and armour since the time of Diocletian at the end of the 3rd century. This one is a reconstruction at the Saalburg Roman fort. 3. Artefactual EvidenceAnd FinallySo there you have it. It's been a pleasure to explore this topic; digging into what seemed to be a yes/no question at the outset has allowed me to understand the era I love just that little bit more. I hope you've enjoyed the discussion too ;) And if you'd like to read about the legionaries who faced the Gothic horde, you can relive those fraught times in my Legionary series! References

1 Comment

3/11/2021 07:32:25 am

Nancy took her daughter Donna to the park. The park had lots of trees. It had lots of squirrels and birds. <a href="https://mgwin88.info/juad88/">JUAD88</a>.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed