|

I've been listening to the brilliant 'History of Byzantium' podcast for years. So it was a real honour to be the guest on this most recent episode!

Even better, it contains details of a comp to win a signed copy of my book 'Strategos: Born in the Borderlands'! Have a listen (and apologies in advance for my dalek-esque tones! ) :

0 Comments

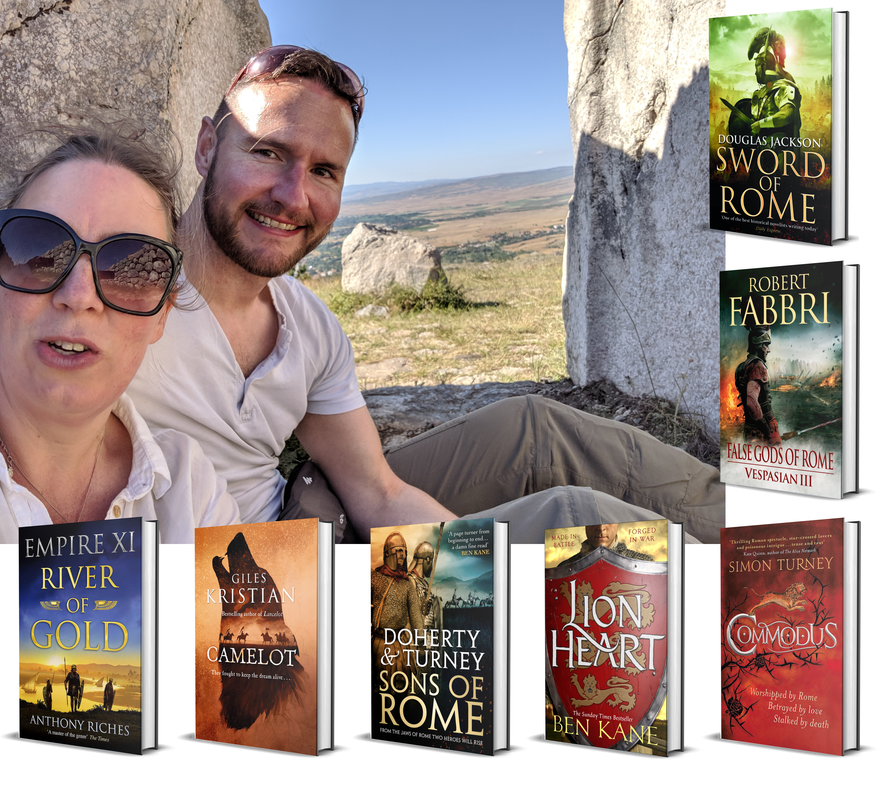

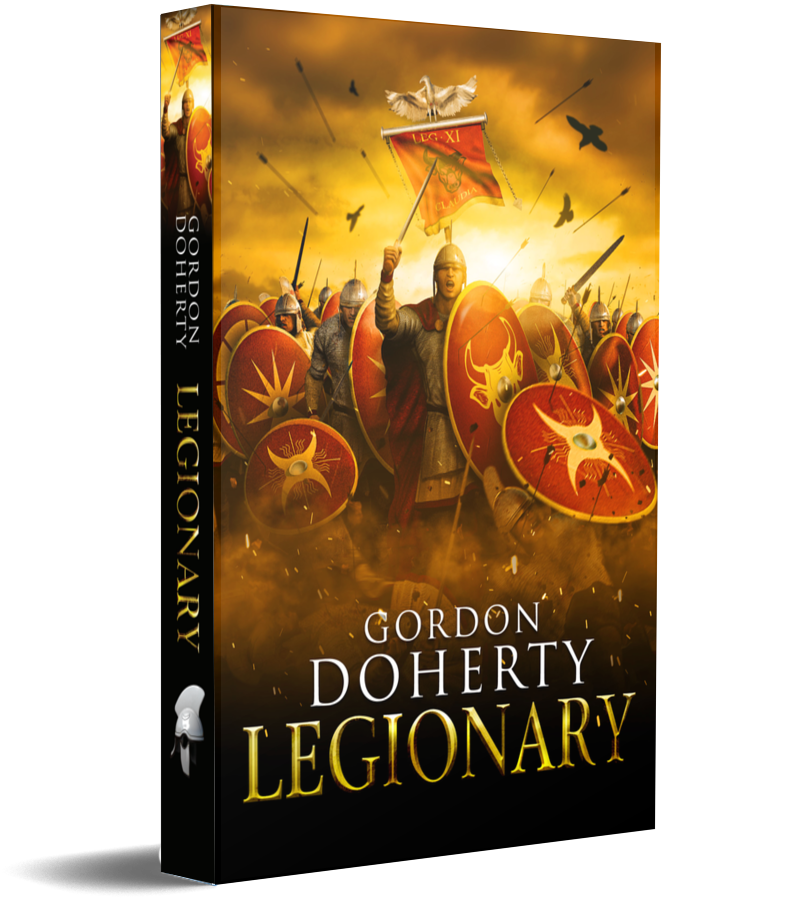

If you haven't already noticed (where have you been?!), a new book series is storming the book charts - Viking Blood & Blade, by Peter Gibbons. The Viking era is very popular, but the way in which this saga is written is truly magical, weaving high adventure with all the violence and brutality of the period with a soulful and moving character journey. Today, it is my pleasure to chat with Peter about history, writing and life, here on my blog! Question: History is absolutely littered with really juicy stories. As a writer, I feel constantly pulled to many different eras. What drew you to the Viking period specifically and made you think 'this is it'? I agree, there are so many exciting periods and events across history to write about. I have always had a particular interest in the ancient world, Sparta, Macedon, Rome etc. But I chose the Vikings for my first series of books because I think it's a period in time which people can relate to, in a strange sort of way. For people in the UK, especially in the north of England, we can still see and feel the Vikings all around us in place names and family names. Also, it's a similar story in Ireland where I currently live. Dublin is a Viking city, as is Waterford, and where I live in Kilcullen in Kildare there is a plaque by the river Liffey which boldly states that the Vikings raided nearby - which is certainly inspirational! The series moves from Viking Age England in Viking Blood and Blade, to France in The Wrath of Ivar, and then on to Ireland in the third book Axes for Valhalla. I know those places very well, so I think it made sense to start my writing career with places I am familiar with. Question: Hundr is a really compelling protagonist. Is there a little bit of you in there, or did you create him from scratch? I created Hundr from scratch. I wanted to pick a big story in the Viking Age - and what story is bigger than Ivar the Boneless and the Great Heathen Army - and put a little story within it. The little story is Hundr's story. I wanted to create a character who has to find his way in the brutal world of the Vikings, but who also has his own interesting backstory which can be teased out and explored in future books. He has one great skill - which is his training and proficiency with weapons. That certainly came in useful in the Viking Age! But other than that, he is as human and fallible as all of us. I wanted him to be vulnerable, and to not always make the right decisions, and also to lose sometimes... In the first three books we have only seen Viking Age England, France, and Ireland, but in future books I do plan for Hundr to travel to Scandinavia, and eventually on to the lands of the Rus, and maybe even south to Constantinople - if he lives that long... And as for the historical cast, your take on Ivar the Boneless is quite incredible! Can you give a short background on him for readers who (like me until very recently) haven't heard of him?  A depiction of the historical Ivar the Boneless. A depiction of the historical Ivar the Boneless. Ivar is one of my favourite historical characters. One of the most interesting things about well known Viking war-leaders and Kings is the brilliant names they gave each other. Erik Bloodaxe, Bjorn Ironside, Ragnar Lothbrok, Harald Bluetooth, to name a few of the best ones. Ivar and his brothers Sigurd Snake Eye, Bjorn Ironside, Halvdan, Ubba and Hvitserk were the sons of a great hero of the Norse Saga's; Ragnar Lothbrok. Ragnar is a semi mythical figure, but the story goes that he was a great raider and hero who was eventually shipwrecked off the coast of Northumbria in England, and captured by the Northumbrian King Aella. Aella threw Ragnar into a pit of snakes, and as he died Ragnar called out "how the little pigs will grunt when they hear how the old boar died." The little pigs were his sons Ivar et al. Ivar and his brothers swore vengeance on Aella and swore to invade and ravage the Saxon Kingdoms of England, which they did! Ivar is famous for his terrible methods of torture, when he eventually caught King Aelle he subjected the unfortunate King to the "Blood Eagle." What I like about Ivar is the sheer daring in his venture, so gather together an army of warships from Denmark and sail them to England to wage a war which would see him eventually become ruler in York (which was called Eoforwich by the Saxons, but the Vikings couldn't pronounce the word and it quickly became Yorvik and then York), and years later he became the King of Dublin. Historians have speculated that his name indicated that Ivar had a disability, that his epithet of "the boneless" meant that he lacked bones or legs, or perhaps that he was impotent...! In the Vikings TV show, they portray Ivar as being unable to walk, but I very much see Ivar as a great warrior and soldier. So, my version of Ivar gets his name from his battle skill, and his ability to move so fast it's as though he has no bones in his body, and I made him handsome just to subvert the traditional "baddie" trope. Question: In terms of writing craft, you must have found your approach changing as you moved past your first novel and went on to write parts 2 and 3. What would you say has been the most radical shift in your process? My writing process has definitely changed over the course of the three books. The first novel was very much a voyage of discovery in terms of story structure, writing style and plot development. I wrote that book in the traditional "pantser" style of writing, where a writer just puts pen to page (or finger to keyboard!) and discovers where the story goes. The second and third book were both planned and plotted in advance of writing, which I think I prefer and is probably the most radical change. I like to have a genesis of an idea, flesh it and build into a coherent structure, and then develop the plot. Question: Where do you stand on the 'historical accuracy' vs 'a damned good story' spectrum? This is a tough question - but at the risk of sitting on the fence - I think you need to have both and that it depends upon the period of history in which the story is set. The historical setting is the backdrop for the story, and the reader has an expectation of accuracy and research from the author. But, the story is paramount and I do think it's OK to change elements of the historical facts if it serves the story. If it's a period where the evidence is sparse and open to interpretation then it makes it easier to forge the facts in the interests of the story. But, if one was writing about Julius Caesar where there are buckets of documentary evidence, then it's harder to bend the facts and readers would expect the story to be historically accurate. For example, in the recent Vikings Valhalla Netflix series, they have moved Harald Hardrada back in time so he can inhabit the same world as other characters such as King Canute, Leif Eriksson etc. That's OK because now we get to have lots of cool characters inhabit the same story! Question: Viking Blood & Blade is soaring high in the book charts. Having chosen the self-publishing route for this series, you've achieved this entirely off your own back which is really, really impressive (I know from my own so far fruitless efforts to hit such heights). What approach did you take to marketing and spreading the news about the series? You are being very generous in your praise Gordon, I know first hand that your books are brilliant and that you have been super successful in your own right. I am simply following the trail already blazed by authors like you. For a self published author, marketing is almost as important as writing. If you want people to see your book, and for it to be in any way successful, then an understanding of marketing is paramount. Fortunately, Amazon is amazing and provides tools and training to help authors. I haven't really done much in the way of social media, but I am working on that now and realise how important it is. For any self published author, I would say that an understanding of metadata, cover design, and online advertising is very important. Question: Can you give us a line or a short scene from the series that will send a shiver up the spine? To avoid spoilers, I think a good chiller of a scene takes place in book one where Ivar cuts the Blood Eagle into King Aelle's back. This actually happened, so its gruesomeness is a real event and that is what makes it so chilling. Ivar works on King Aelle's back with axe, knife and chisel. He chips the King's ribs away from his spine carefully so that Aelle remains alive throughout the process. He then opens up the ribs and flesh of the king's back open so that they resemble an eagle's spread wings, and hauls up to a hanging position, the ribs then burst the King's heart and he dies. What a way to go! Apologies if I have put anyone off their cornflakes with that one.... Final Question: please tell me there are more works to come from you? :-) I have a new book which I am just finishing, it’s a Saxon adventure in keeping with the genre which I will publish in the next couple of months. I also wrote a historical fantasy novel some time ago which I am trying to whip into shape. It’s set in the ancient world and starts at the time of Cyrus the Great and his battle with Tomyris and the Massagetae and then on to the time of Alexander. It’s a time travel/magic system type novel (I love a bit fantasy!) Thank you, Peter. What an interview. It's been brilliant to have you on the blog. May your words continue to flow! I recently did an author interview over at The Historical Fiction Company, which was great fun. I thought I'd republish it here, in order to add all the extra photos and titbits that would make it even more fun. So, here we go... Question: What literary pilgrimages have you gone on?I give you, The Great Hittite Trail! This was our last jaunt abroad before the pandemic hit. What an epic overland adventure it was, taking in Istanbul, Ankara, Erzurum, Tbilisi and more. This took us right through the spine of what was, 3,000 years ago, the heart of the Hittite Empire, and really grounded me for my Hittite series Empires of Bronze. A few years before that, I hired a car in Istanbul and ventured northwest towards the Turkish-Bulgarian border, in search of the site of the famous Battle of Adrianople – crucial to my Legionary series. Question: Tell us the best writing tip you can think of, something that helps you.“The first draft of everything is shit”, is a quote attributed to Ernest Hemingway. I can confirm that my first drafts certainly are 😊 But that’s the point – they give you something to work with and make better. Just as Michelangelo needed a brutish block of marble in order to create David! “The first draft of everything is shit.” I now refer to my first drafts as “The vomit draft”. Just let it all come out onto the page, rattle on through it, don’t get sidelined by intricate historical detail (just leave a comment or highlight at that point and you can come back to it later). So that’s my tip: vomit! Question: What are common traps for aspiring writers? Advice for young writers starting out.Overreaching is one common pitfall. You don’t need to start with a Great American Novel. Start bite-sized, with flash fiction (just a paragraph or a page in length). It is a rapid and very powerful way to understand and tame the raw emotions that come out when you first try to write. Question: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be? Be yourself. In the early days, I tried too hard to imitate the authors I liked. It was fun, but it wasn’t authentic. My wife (chief editor!) showed me this, and it changed entirely how I approached things. I am still definitely influenced by other authors, but I always tell my stories my way. Question: What other authors are you friends with, and how do they help you become a better writer?Writing is such a solitary profession that friends become essential. I’ve met too many wonderful, supportive people to mention them all here, but take a look on my Facebook author page where I run weekly charity auctions (for signed rare editions of historical fiction novels) – just about everybody in the HistFic community has helped me out with this, and that is simply awesome! If any authors out there would like to feature their work in my auctions, just drop me a line! Specifically though, I have to shout out to my pal Simon Turney. We met in the mid 2000s when we were both trying to get started with our writing careers. We have been critiquing each other’s stuff and bouncing ideas between each other… as well as drinking a fair few pubs dry, ever since. The high point of the friendship – so far – has to be our recently-released trilogy Rise of Emperors where we tell the story of Constantine the Great’s Rise to power and his famous battles with his mighty rival, Maxentius. Question: How did publishing your first book change your process of writing?I was overwhelmed (in a positive way) by the amount of kind words coming in from readers of my first novel Legionary, and the same question always followed: ‘when is book 2 coming out?’ It was at this point that I realised I was at least passable as a writer. It made me realise that I couldn’t rely on the trial and error approach that I took with Legionary – the writing, redrafting, experimenting of which took nearly 5 years! Thus, I tried to avoid the things that sapped precious time from my writing sessions (I was still working full time at this point, so this meant evenings and weekends were all I had to write my stories). I set up a proper project workspace on my PC, consolidated my research into quick-reference documents, and planned out the rest of the series, so I was marching as opposed to wandering. Question: What was the best money you ever spent as a writer?Easy: Pro cover design. This is hardly a new piece of advice, but it is a brilliant one. I launched Legionary with my own, hand-rolled cover, which was… er… a valiant effort. But by paying a few hundred pounds to a pro designer, I tripled my sales overnight, and the Legionary series really kicked on from there. Check out the before and after: Question: What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?I learned this from reading. I recall vividly and with great pleasure (absurd, given the circumstances) the few weeks of my childhood when I was off sick from school with chicken pox. I spent that time in bed, ploughing through the Chronicles of Narnia. I had never experienced such magic. This inspired me to try writing my own stories, and I quickly realised that the pen was equivalent to the wand, and the writer to the magician. Question: What’s the best way to market your books?I’m still working on that, to be honest! For the first few years of my writing career, I did very little marketing. Maybe an email to my subscriber list on launch day, and a post across the usual social media suspects. It’s only in recent times when competition is fierce and widespread that I’ve realised I need to train myself in a little more active marketing. I’m currently working on Amazon and Facebook ads. Quite daunting at first, but as always it’s enjoyable when you feel yourself gliding up the learning curve. Question: What kind of research do you do, and how long do you spend researching before beginning a book?I’m primarily an armchair researcher. Give me my writing room sofa, a cup of coffee, my Kindle, a pile of books and my cat and I’m happy as larry. But… you simply can’t beat a research jaunt! As per my link, above, I took a trip across central and eastern turkey and up through the Caucasus Mountains and through Georgia as part of my research for my Hittite Empire series ‘Empires of Bronze’. This was utterly unforgettable. Meeting locals, playing with the kids in the villages near the ruins of Hattusa (the old Hittite capital in central Turkey), smoking shisha pipes and drinking beer beside the ruins of the Byzantine Emperor’s palace in Istanbul… I’m sighing fondly as I write this. How long do I spend? It depends. For the first book in a series I tend to set aside a few months to really immerse myself in the period. And that usually follows several years of on/off casual research to see if it’s the project for me. For subsequent books in a series, it requires a bit less research time – it’s more slipping into a familiar pair of boots. Question: Have you read anything that made you think differently about fiction?Albert Camus once said “People can think only in images. If you want to be a philosopher, write novels.” I realised the truth of this around the time of completing my first book. Deeply personal things were coming out in the story, sometimes as metaphors, sometimes directly. It wasn’t all about marching, war and adventure. It was about questioning life’s paradoxes, about understanding the flawed, nuance nature of people. I’m quite into Stoicism these days, and that tends to come through in my more recent books. “People can think only in images. If you want to be a philosopher, write novels.” Question: What are the ethics of writing about historical figures?

Question: Do you read your book reviews? How do you deal with bad or good ones?Course I do! Anyone who says they don’t is fibbing 😊 I’m human, so initially, the good ones made me ecstatic and the bad ones made me grumble. More recently – taking the Stoic approach – I just let it all glide past me. You can’t please everyone all of the time, and you’d be a fool to try. Question: What is the most difficult part of your artistic process?I wouldn’t say the most difficult… but maybe the most ethereal part of it is the development of themes and characters. I can, and always do, sketch these things out as part of my planning. A character sheet for every protagonist, a list of themes and how they might tie in with the plot. But it never, ever pans out that way. The characters emerge in their true form during the writing, not before. The real themes smack you right in the face and make you realise that they’ve probably been lurking in your sub-conscious for an age. For example, while writing my sixth Empires of Bronze novel recently, I found myself describing a dangerous wave of populism sweeping like wildfire across ancient Anatolia. It’s not surprising that this came through really, given the way the modern world has gone in the last decade. Question: What is your favourite line or passage from your own book?‘The End’… ...only kidding 😊 There’s always a ‘shiver’ line in each book. Some of them don’t stand the test of time, however. Here’s one I like from my most recent volume Empires of Bronze: The Shadow of Troy. The Greek hero Achilles, having just slain Prince Hektor in revenge for the killing of his close companion, Patroklos, has stripped the dead Trojan prince naked and tied him by the ankles to the back of his chariot. He then proceeds to race up and down before Troy’s walls – atop which Hektor’s distraught family stand, watching on – dragging the corpse in his wake. I have Hattu – King of the Hittites – intercept Achilles at a blind spot. He tries to persuade Achilles to end the gruesome parade with the following line: “That is but a rotting shell you drag behind your war-car. You can pull it around all day, but it will never blush or weep or beg for mercy. The only man I see suffering here is you, Achilles.” Question: What was your hardest scene to write?The death of one of the key players in the Legionary series cut me to my marrow. I won’t give away names in case anyone wants to read it without spoilers, but this guy was the father figure in the series. I had a complex relationship with my own father, and only recently lost him. There was a lot of me and him in that writing. Question: Finally, tell us your favourite quote and how the quote tells us something about you.Sometimes I need something to ground me, to keep me calm. This, from my literary hero David Gemmell, works every time: 'All things in the world are created for Man, yet all have two purposes. The waters run that we might drink of them, but they are also symbols of the futility of Man. They reflect our lives in rushing beauty, birthed in the purity of mountains. As babes they babble and run, gushing and growing as they mature into strong young rivers. Then they widen and slow until at last they meander, like old men, to join with the sea. And like the souls of men in the Nethervoid, they mix and mingle until the sun lifts them again as raindrops to fall upon the mountains.' So there you go - hope you enjoyed the Q&A! 😊

Happy #HistoryWritersDay!

Have a discount, on me, for the first book in my 'Empires of Bronze' series - 'Son of Ishtar'.

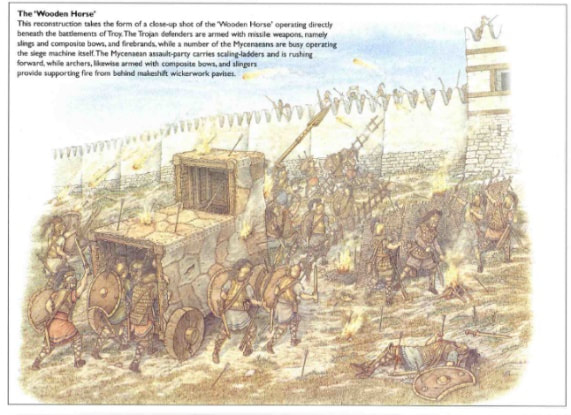

...and it's yours for 99p. Enjoy! The code will work until 5th Dec 2021 :) The Trojan Horse is iconic and legendary, yet it is not mentioned even once in Homer's Iliad. In fact, in the entire eight texts of the Epic Cycle , it is only mentioned once and in passing in Odyssey, which tortures us with just a single line: “A single horse captured Troy... We have no firm idea what this ‘horse’ actually was. The traditional narrative is probably most well known, and the sequence of events is:

However, the notion of men hiding within the horse first appears only in the Roman age with Virgil's Aeneid. It does seem like a poetic invention. There are many more theories, wide and varied:

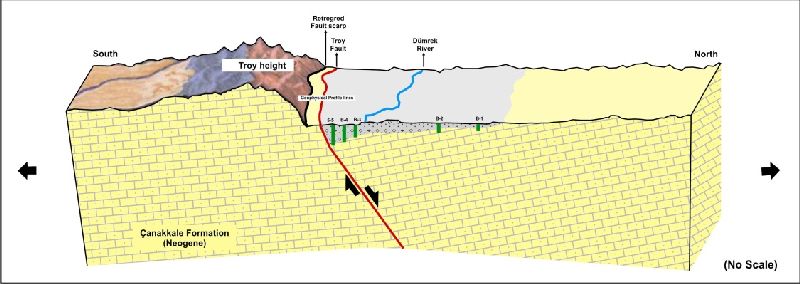

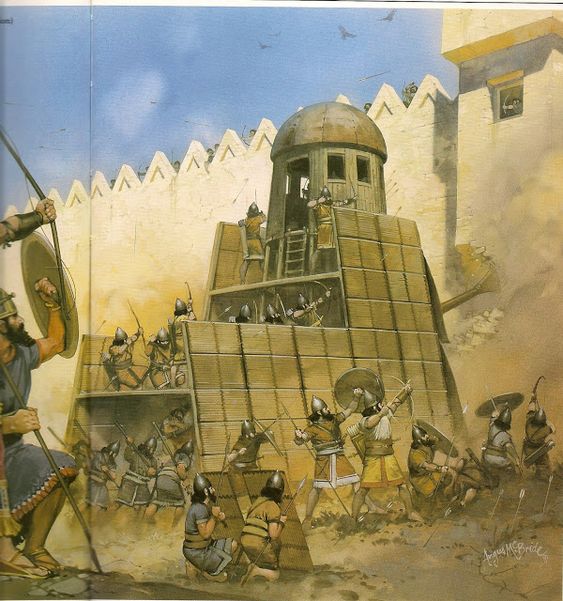

There are even other theories, and the one makes most sense to me as a historian is that the horse was a siege device. Later writers Pausanius and Pliny the Elder were both convinced that this was the case, the former stating: “Anyone who doesn't think the Trojans utterly stupid will have realized that the horse as really an engineer's device for breaking down the walls. Siege technology in this age was advanced. Some devices were often named after animals – The Assyrian Horse, the Wild Ass, The Wooden One-Horned Animal. Assyrian tablets depict the first of these as a ram shed with a ‘neck and head’, the head containing a drillbit used to pick apart walls. One can see in it the visual resemblance with a horse. The siege engine theory is just one of many that I write of in my latest novel The Shadow of Troy!

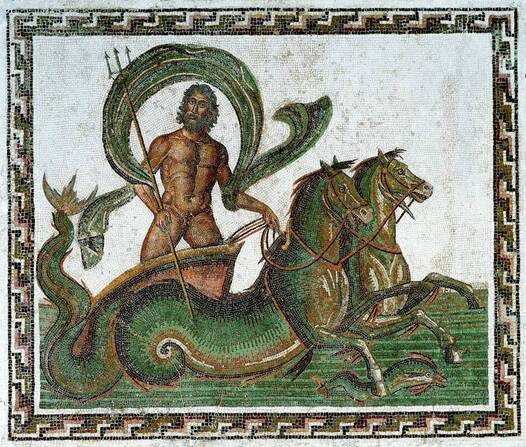

What are your thoughts and theories? Please do leave your ideas in the comments section, below :) So I returned to the Watling Lodge stretch of the Antontine Wall at the weekend. The place is something of a sanctuary for me - a green, wooden vale that feels like it is in the middle of nowhere (when in fact it is in the heart of the Falkirk suburbs). I particularly like the LiDar imagery (assuming that is what it is) on the new plaques, showing the topography of the wall region. This technology promises to revolutionise archaeology! And here's my video from a few years ago touring the Watling Lodge area. Offer still stands of a free copy of the short story I wrote about the place :) The Trojan War. Everyone knows at least the kernel of the story: Prince Paris of Troy abducted Helen, Queen of Sparta. Incensed, the Greeks gathered a giant army, landed at Troy and besieged the city for 10 years. You might know of the legendary characters: Hektor, Achilles, Priam, Odysseus. Or the factions - the Amazons, the Myrmidons, the Elamites and many, many more. But there is one almighty whopper of a 'faction' that is not mentioned at all in Homer's Iliad. The Hittite Empire - not just an ally of Troy, but her behemoth overlord. You see, the Trojans, plus many of her allies, were for centuries in the Late Bronze Age, merely vassal kingdoms, serving the Hittite Emperor. The near east map of the Late Bronze Age, below, puts some perspective on this. Note: 'Ahhiyawa' was the Hittite name for Homer's Greeks/Achaeans. So where were the Hittites in Troy's hour of desperate need? Homer's Iliad does not even contain a passing reference to them. This is akin to Latvia and Estonia going to war and nobody ever mentioning Russia. However, The Iliad covers just a few months in the 10th and final year of the Trojan War, ending with Hektor's funeral. The things that happened between then and the actual end of the war – the coming of the Amazons and the Elamites, the deaths of Paris and Achilles, the horse, the sacking of the city et al – survive only in the tantalising fragments of the other ancient texts that make up what is known as The Epic Cycle. Regardless, as fragmentary as those texts may be, none of them mention the Hittites either! What’s going on there? One theory is that the Hittite Empire had collapsed by the time of the Trojan War. However, we know that the Greek world collapsed before or at roughly the same time as the Hittite world, so if the Hittites were gone, then so too must be the Greeks, and how could there be a Trojan War then? And even if the end of the Hittite Empire preceded the fall of Homeric Greece by several years, one would expect there to be at least an echo of the Hittites in The Iliad - successor or splinter empires, that kind of thing Most likely, I think, we are looking too hard and too literally at The Epic Cycle texts for a mention of the Hittites. After all, the name ‘Hittite’ didn’t actually exist in the Late Bronze Age. The Hittite people actually referred to themselves as ‘The People of the Land of Hatti’. More, Egypt knew them as ‘The Khetti’. And that’s where one theory arises: Odyssey, the tale of the Greek hero Odysseus’ tumultuous and circuitous voyage home, contains a passage of exposition about the war which mentions the arrival at Troy of a small force known as ‘The Keteioi’ who came to help the defenders.. In the final year of the war, following the death of Hektor, these 'Keteioi' turned up and became one of Troy’s last hopes. Could these Keteioi be the Hittites? It is a frustratingly flimsy deduction but intriguing nonetheless. Certainly, it seems more plausible at least than other wilder theories – that the Amazons were in fact the Hittites (owing to the Hittites' long, dark ‘feminine’ hair and shaved chins), or that a minor Trojan ally, the Halizones, were the Hittites. “Now as we have come to an agreement on Wilusa over which we went to war.” Onomastic similarities (similar-sounding names) aside, there is another compelling piece of evidence that the Hittites could have been at the Trojan War in some capacity. It stems from an excavated Hittite tablet known as the 'The Tawagalawa Letter', named after the brother of the Greek King to whom it was addressed. This tablet is dated to the reign of the Hittite King Hattusilis III (1267-1237 BC), and mentions a conflict over Troy between The Greeks and the Hittite Empire, roughly dating to 1260 BC. Could the 'Keteioi' of Odyssey and this 'Tawagalawa Letter' conflict be evidence that the Hittites took part in the legendary war? Perhaps. It is certainly not concrete evidence, but definitely intriguing. Now, if we work on the assumption that they were at the war, we must then ask why they made so little impact. The Hittite Empire was - only a generation earlier in 1274 BC - the greatest military power in the world, having just turned the mighty Pharaoh Ramesses and his Egyptian armies away from Kadesh in another of the Bronze Age's famous clashes. Surely the Hittite armies should have turned up at Troy and been able to steamroller the Greeks? To understand why this apparrently didn't happen, we must look a little closer into the goings-on in the Hittite Empire during the short gap between the wars at Kadesh and Troy... Around the time of the Trojan War, King Hattusilis III had only recently claimed the Hittite throne from his nephew, Urhi-Teshub. He decided to exile rather than kill the previous incumbent, though he must quickly have realised that this was a huge mistake. Many of the vassal kingdoms, sensing that the exile might be on the brink of returning in an effort to reclaim the throne – bringing war and retribution with him – wavered in their loyalty to King Hattusilis’ rule. Hattusilis was also plagued by jibes of illegitimacy from mocking foreign rulers. The Great King of Assyria – a rival empire – sent neither envoys nor gifts to Hattusilis coronation ceremony, and went as far as to label him as ‘A substitute for the real Hittite King’.

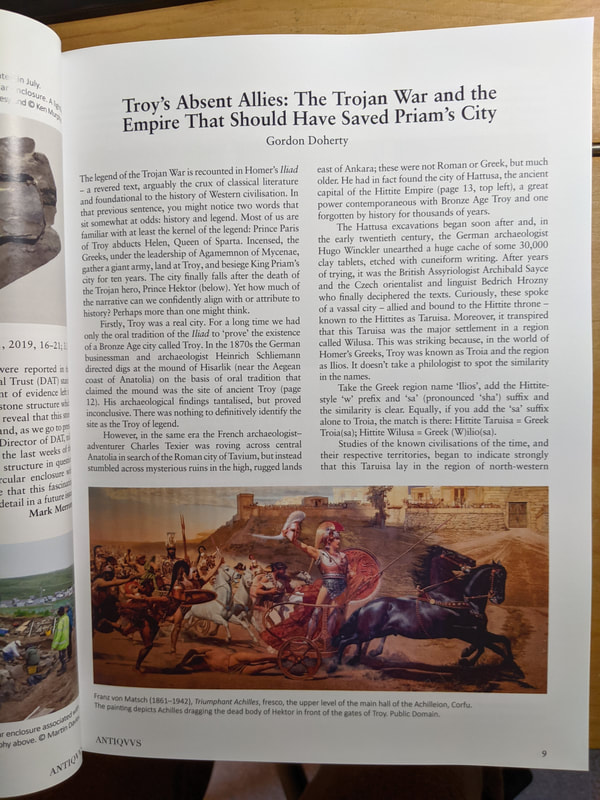

Sensing trouble, Hattusilis sought new allies. The greatest agreement of this kind was that which he struck with Ramesses II of Egypt. He and his erstwhile sparring partner from Kadesh agreed what is known as ‘The Eternal Treaty’ or ‘The Silver Treaty’, which laid out the conditions of a defensive alliance between the Hittites and the Egyptians. This effectively mitigated the huge threat posed by Assyria, and plausibly would have freed Hattusilis and his Hittites up to tend to the long unanswered call for help from Troy. Yet any force he might have taken to Troy would have been likely been severely depleted from the recent war to oust his nephew. This could tally with the attested small contingent that the Keteioi brought to the Trojan War. The Odyssey does not describe what the Keteioi went on to do upon their arrival. So I have taken up the challenge to tell the story on the premise that they were, in fact the Hittites. The Shadow of Troy tells the tale of the epic climax to the greatest war of all time. Quickie blog this time - just wanted to shout out about an article I wrote about the historical background to The Shadow of Troy, in the autumn '21 edition of Antiquus magazine.

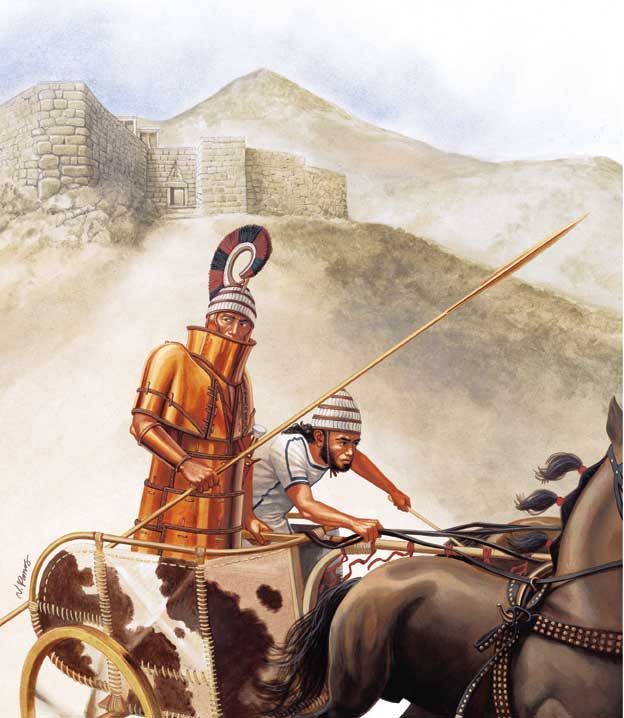

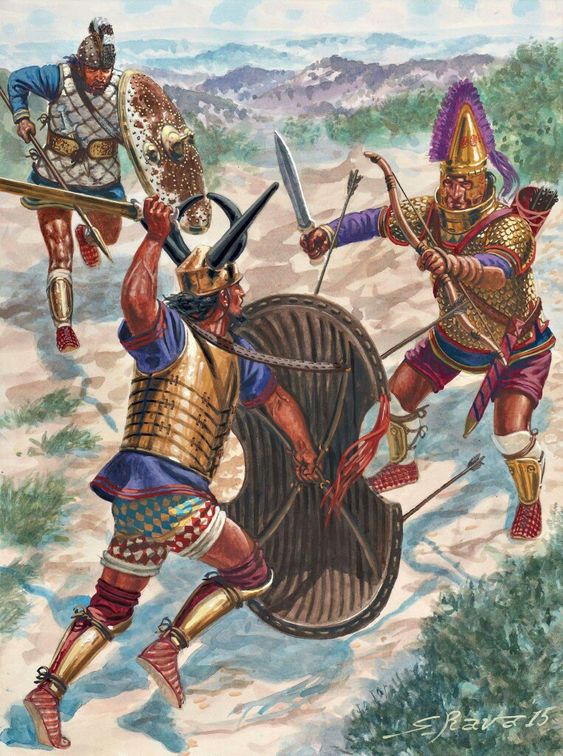

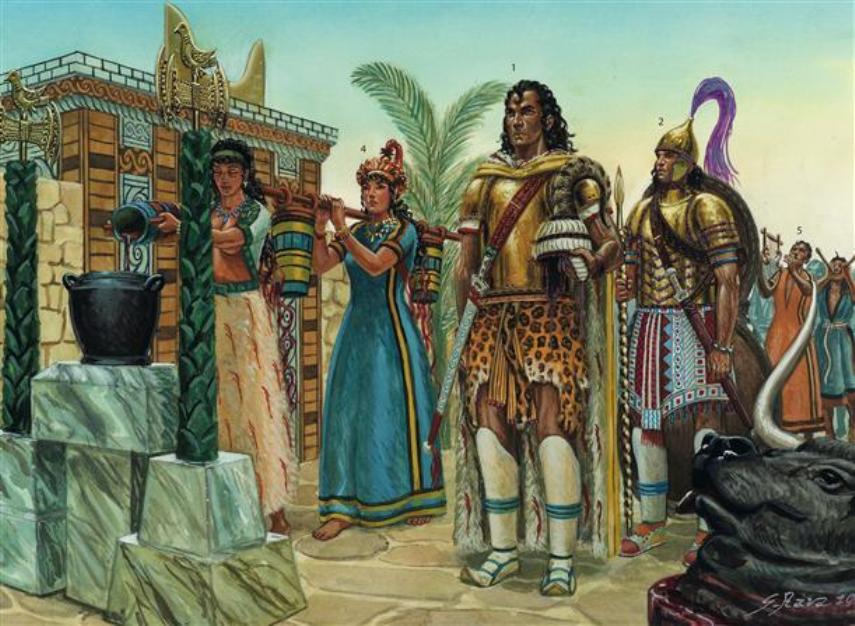

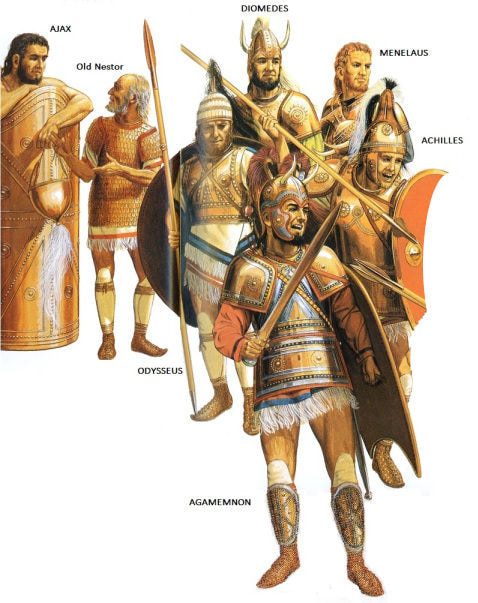

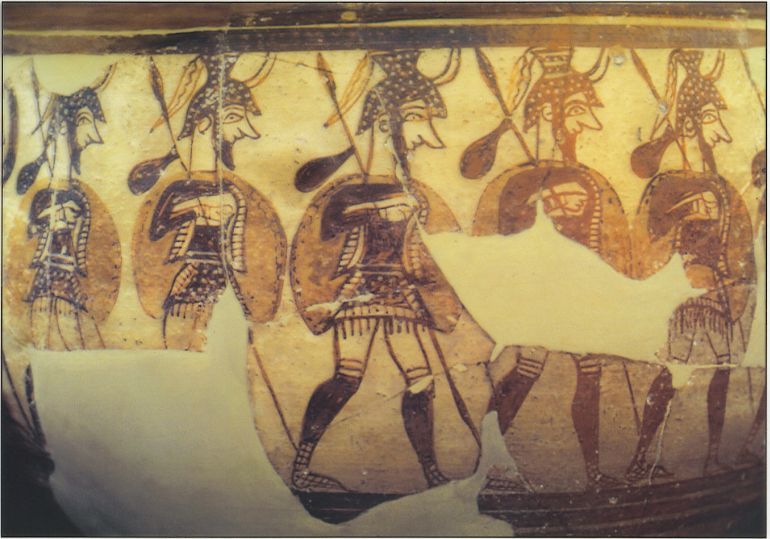

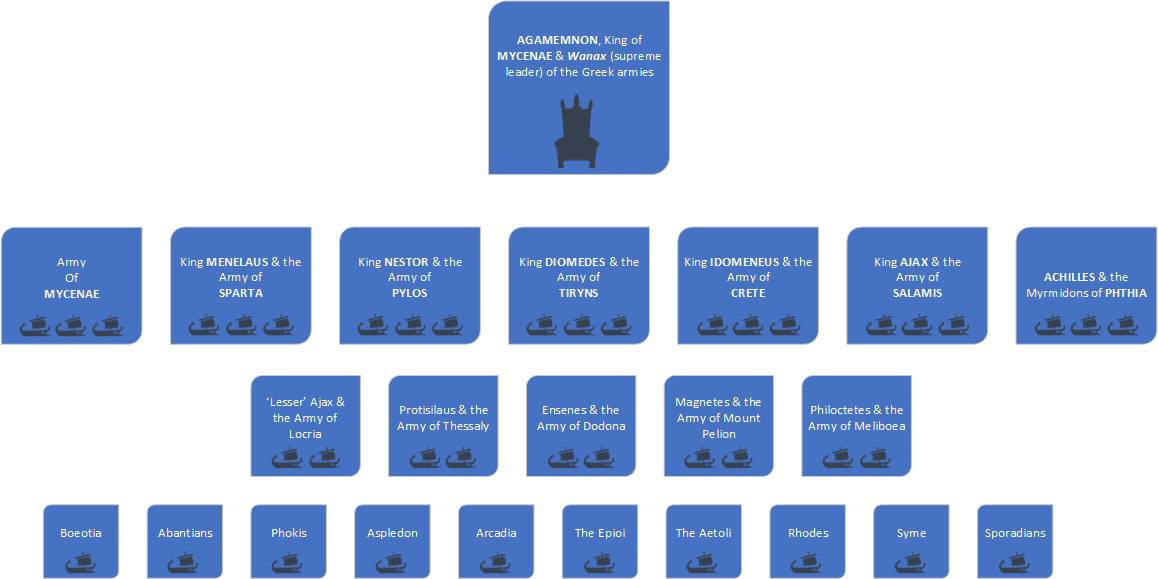

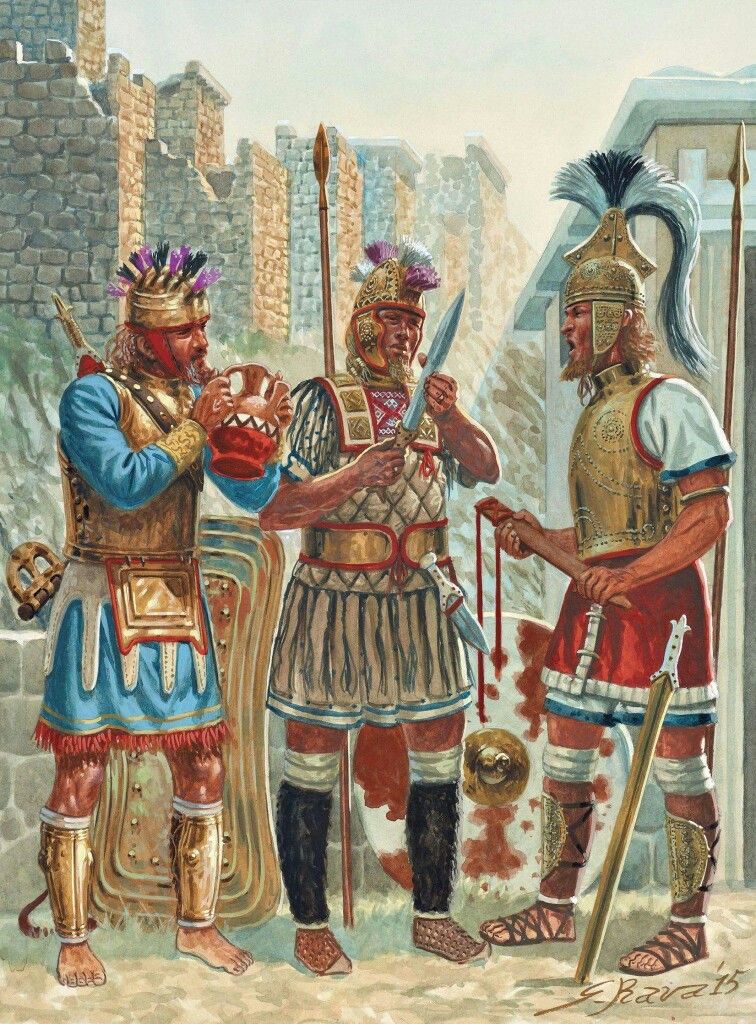

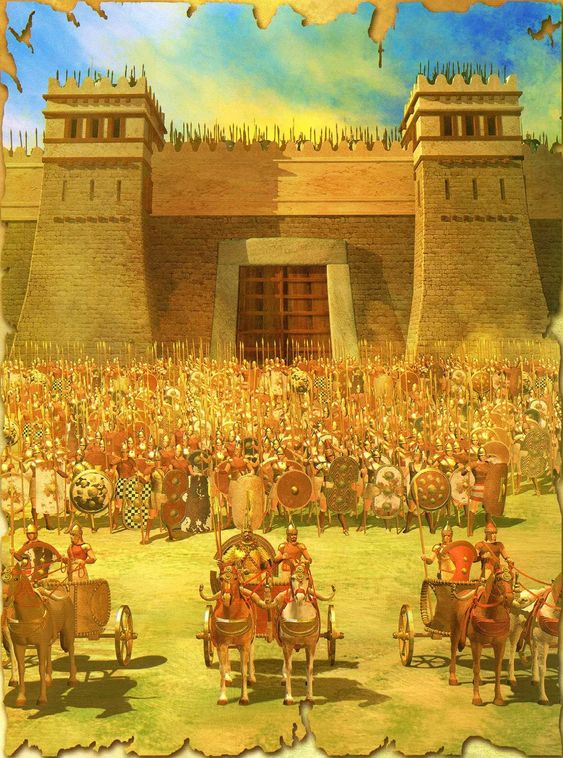

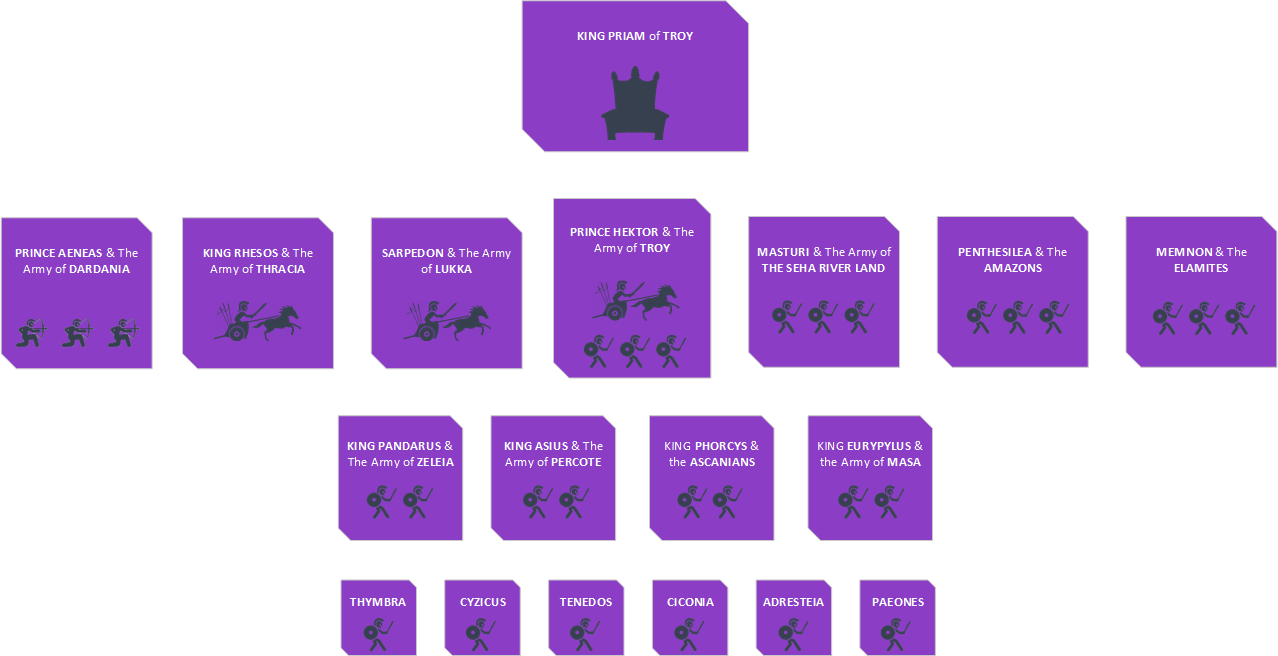

Nice to see my ramblings in glossy format! Also, it was great to work with the team there, and to discover all the other historical content they cover. The legend of the Trojan War has held the attentions of countless generations - from those who lived in its aftermath right through to the present day. Why the eternal fascination? Personally, I have never been able to leave along the thought of what might have been had Hektor beaten Achilles. Could it have tilted the balance of the war in Troy's favour? Then again, if it had played out like that, perhaps the epic tale might never have been born. Troy had to fall in order to become the legend that it is. Had King Priam's army and those of his allies staved off the Greeks and sent them scuttling back to their homeland*, would that tale of a failed siege have been as worthy of lore? Maybe, but it would have a very different spin on it and would be composed by a Trojan bard no doubt**. *There are theorists out there who speculate this might actually have happened, and that the tale of Greek victory is a huge piece of fabrication. **Tantalizingly, Calvert Watkins of Harvard University suggested that some as-yet untranslated Hittite texts might contain the remnants of what he called a possible "Wilusiad". This would have been, he hypothesized, another historical epic about the Trojan War but one written from the perspective of the Trojans or the Hittites rather than the Greeks. Imagine! Thinking on this for the thousandth time put me in the mood to have a look at the attested forces who waged the war. For it was they, not just Hektor and Achilles, who fought out this conflict. What follows is an attempt to put a plausible shape and size to the two forces who battled over the city some 3,200 years ago. The Greek ForcesThe armies of the Greeks ('Ahhiyawans' to the Hittites or 'Achaeans' in Homeric parlance) were led by Agamemnon, the warrior king of Mycenae. Greece of this era was not in any way a nation. Instead, the rocky peninsulas and archipelagoes housed a number of small but powerful city-states, each of whom considered themselves proudly independent. So it was no mean feat when Agamemnon managed to bind them together into a unified force for the assault on Troy. Legend has it that he achieved this by citing the Oath of Tyndareus - when Queen Helen of Sparta chose to marry Menelaus, all of her rejected suitors swore to protect the marriage, so when she absconded with Prince Paris of Troy, they were obliged to unite and act. But in reality, without such a glittering prize as Troy, it is highly unlikely that the joining of the many city-states could have occurred or held for as long as it did (the Trojan War supposedly lasted some ten years). Agamemnon's forces gathered at the port of Aulis for the expedition to Troy. What kind of army would this have been? Given the largely mountainous terrain in Greece, their style of warfare is likely to have been something akin to that of sea raiders. Thus, the gathered forces are likely to have been largely composed of spear and sword infantry with a small number of elite royal chariots. Homer's Iliad has a very famous scene in it known as 'The Catalogue of Ships' in which he slavishly details every single faction involved in the Greek effort. We also hear of the Greeks attacking Troy with 'one thousand black boats'. Given a warship of the age might cary 30-50 men, this would equate to an army of up to 50,000. Quite simply this is highly unlikely. A force of a few thousand, maybe up to 10,000, is more plausible and for that age and region, still represents a colossal military expedition. There were some major and many minor factions involved. The following graphic (click to enlarge) aims to put some kind of proportional shape to the expedition force. The Armies of Troy and her AlliesPriam was the King of Troy, but the most powerful man in the city was most likely his son and heir, Hektor. Hektor was in his prime, something of a battle-hero and talisman to the Trojan forces and citizens. He, along with his most senior princely brothers Paris, Deiphobus and Scamandrios, would have led the native Trojan army. This would have been a small but elite force, composed of infantry spearmen, archers and a crack wing of war-chariots (such as those who aided the Hittites at The Battle of Kadesh). The bowmen and chariots in particular would have distinguished the Trojan forces from the Greeks: Anatolia (unlike the Greek mainland) sports many flat and sweeping plains - perfect country for the chariot, and a land with a millennia-old archery tradition. As soon as they got wind of the Greek invasion, Priam and Hektor sent a call for help to their allies, a call that stretched far and wide. Friendly states all along the western Anatolian coastal regions arrived, so too did further flung allies - from across the Hellespont and even as far away as Elam (roughly modern Iran). An outline of the known allies is depicted in the graphic below (click to enlarge). The Trojans were most likely outnumbered by the Greeks, but with Troy's walls and highly-defensible position on a coastal mound, they had more than enough soldiery to frustrate the besiegers - indeed, that is probably why the Greeks were forced to employ trickery in the form of the Trojan Horse to finally take the city. One outstanding question remains, however: Just look at the 'world' map of the time (below) - Troy was but one vassal city on the edge of the huge Hittite Empire. And the Trojans had only a generation earlier supported the Hittite army at the Battle of Kadesh, so surely it was time for the Hittites to repay the favour? With the Hittite emperor and his armies - probably the most feared force in the world at the time - Troy need not have been outnumbered. So where were the Hittites, the mighty overlords and supposed protectors of Troy? It just so happens that that's the topic of my next blog - read it here :) Thanks for reading! If you like the history, you might be interested in my fictional take on the war - Hittites included! THE SHADOW OF TROY is available at all good online stores.

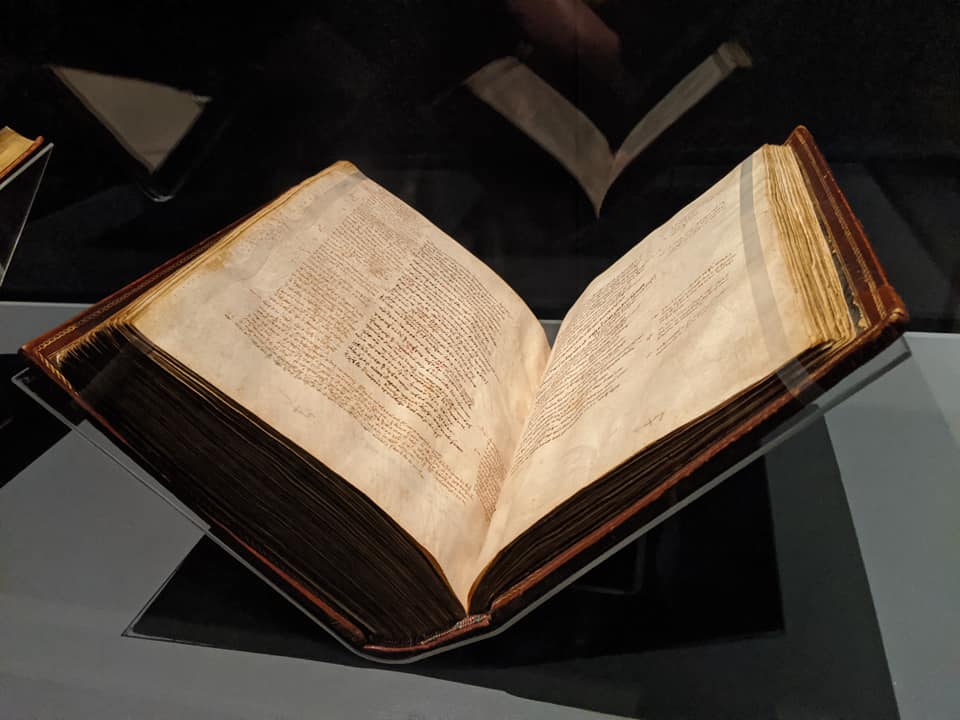

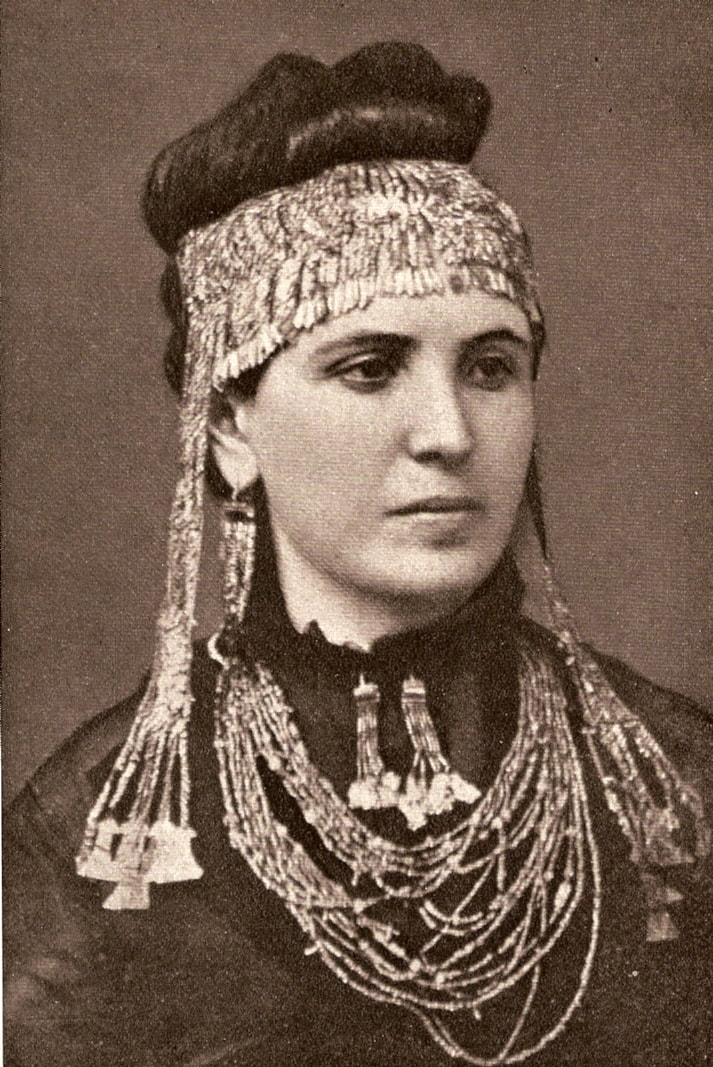

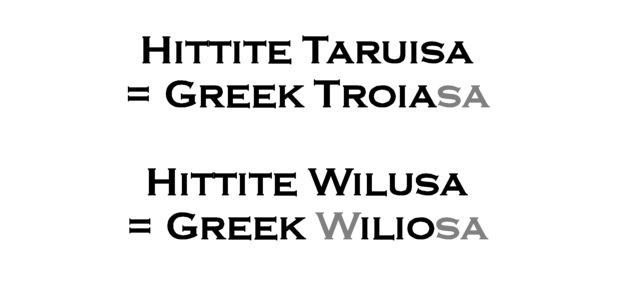

The legend of the Trojan War is recounted in Homer’s Iliad – a revered text, arguably the crux of classical literature and foundational to the history of Western civilization. In that previous sentence, you might notice two words that sit somewhat at odds: history and legend. Most of us are familiar with at least the kernel of the legend: Prince Paris of Troy abducts Helen, Queen of Sparta. Incensed, the Greeks under the leadership of Agamemnon of Mycenae, gather a giant army, land at Troy and besiege King Priam’s city for ten years. After the death of the Trojan hero, Prince Hektor, the city finally falls thanks to the trickery of Odysseus and his Trojan Horse. Yet how much of the narrative can we confidently align with or attribute to history? Perhaps more than you might think... Firstly, Troy was a very real city. For a long time we had only the oral tradition of the Iliad to ‘prove’ the existence of a Bronze Age city called Troy. In the 19th century, Heinrich Schliemann directed digs at the mound of Hisarlik (near the Aegean coast of northwestern Anatolia) to investigate the theory that the mound was the site of ancient Troy. His archaeological findings tantalised, but proved inconclusive. There was nothing to definitively identify the site as the Troy of legend. However, in the same era, the French archaeologist-adventurer Charles Texier was roving across central Anatolia in search of the Roman city of Tavium. In fact, he instead stumbled across mysterious ruins in the high, rugged lands east of Ankara – ruins that were not Roman or Greek... but much, much older. He had found the city of Hattusa, the ancient capital of the Hittite Empire – a great power contemporaneous with Bronze Age Troy and one forgotten by history for thousands of years. The Hattusa excavations began soon after, and in the early 20th century, the historian-archaeologist Hugo Winckler unearthed a huge cache of some 30,000 clay tablets, etched with cuneiform writing. After years of trying, it was Archibald Sayce and Bedrich Hrozny who finally deciphered these Hittite texts. Lo and behold, these spoke of a vassal city – allied and bound to the Hittite throne – known to the Hittites as Taruisa. More, it transpired that this Taruisa was the major settlement in a region called Wilusa. This was striking because, in the world of Homer’s Greeks, Troy was known as Troia, and the region as Ilios. It doesn’t take a philologist to spot the similarity in the names. Take the Greek region name ‘Ilios’, add the Hittite-style ‘w’ prefix and ‘sa’ (pronounced 'sha') suffix and the similarity is clear. Equally, if you add the ‘sa’ suffix alone to Troia, the match is there. Even better, further studies of the Hittite tablets began to indicate strongly that this Taruisa lay smack bang in the region of northwestern Turkey where Schliemann had been digging. In other words we had our first historical attestation of Troy. Secondly, there was a war over Troy in the Late Bronze Age.

Thirdly, the Trojan War might well have happened around 1260 BC. While the war has been ‘dated’ to various decades around the end of the Bronze Age, with estimates spanning 1280-1180 BC, I believe that the war from which the legend derives occurred in the earlier part of that range. My rationale is threefold:

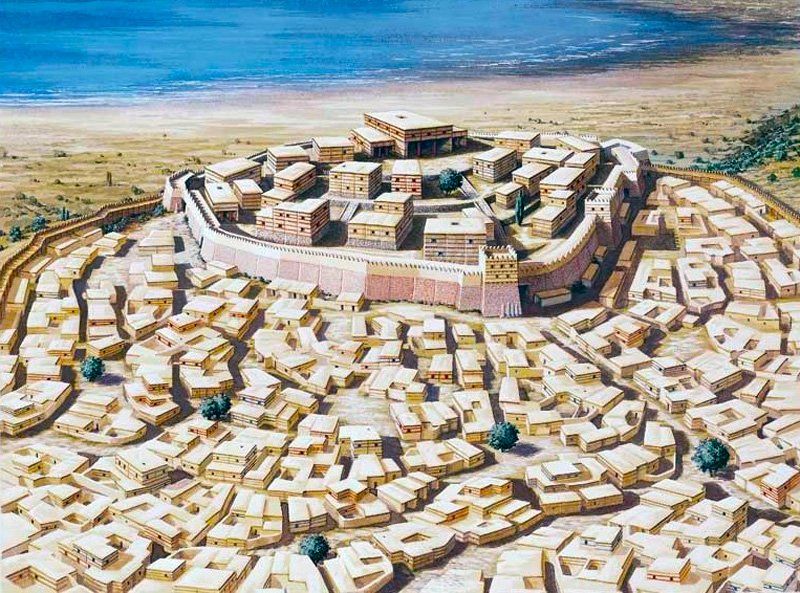

Fourthly, Troy was not a 'Greek' style city. Priam's capital has been depicted in countless works of art, film and literature as a golden city of palaces and orchards, and most often Aegean Greek or even anachronistically classical in style & culture. This is understandable given that the The Iliad is told from a Greek perspective, and was rewritten time and again in the much later classical period. Historically, the city of Troy was almost certainly a cosmopolitan hub – a Singapore of the Bronze Age, a crossroads between east, west, north and south. The city’s markets and in particular her trade ports would have been constantly clogged with merchants – from Mycenae, Egypt, Babylon… even tin traders from distant Britain! Underneath this current of passing trade, I believe that the people of Troy were more likely to have been culturally Anatolian than Greek. Why? The practices detailed in The Iliad – such as Hektor’s funeral ritual with first a pyre then the cleaning and burial of his bones, plus his brother Deiphobus’ immediate marriage to the widowed Helen – are very strikingly Anatolian and specifically Hittite customs. Supporting this angle is the one and only writing find from Troy - a seal, marked not with Linear B Greek language, but with Luwian (Hittite) heiroglyphs. The army of Troy was another thing which would have distinguished the Trojans from their attackers. Agamemnon’s forces – from the mountainous regions of Greece – appear to have been largely composed of spear and sword infantry with a small number of elite royal chariots. In contrast, the Trojan military would have been trained on the sweeping plains of Anatolia – perfect country for archery and horse breeding – and would have comprised more of both bowmen and chariots. Walking in Homer's Footsteps It was with the above historical foundation that I set out to write my story of the Trojan War 'The Shadow of Troy' I assumed I'd fly through the story, what with so much drama and detail to draw upon. But it wasn't as easy as I'd hoped! My first draft turned out to be something of a slavish regurgitation of The Iliad. The Gods weren't present, but almost everything else was: every cut to the hand, every turn of weather and all the most famous poetic lines were in there. So… I tore it up and started again. My goal, you see, was never to simply recount the tale that Homer had already told so well. I wanted to get under the skin of the legend, to understand how things might have been in the pauses between the verses of The Iliad... to match up the poetry against the historicity of the excavated tablets and finds. I thus opted to omit and truncate many events and minor characters in order for The Shadow of Troy to be the story I wanted it to be. This allowed me great freedom to write about the grimier, guerrilla-style military necessities which surely must have accompanied the heroic one-on-one duels, to portray more plausibly the likely numbers of troops on each side, and to examine the primal trauma such a brutal war must have caused the individuals involved - the painting ‘Ulysses and the sirens’ by Herbert Draper, captures this theme with haunting perfection.  'Ulysses and the Sirens' by Herbert Draper. In it we see Odysseus on the way home from the Trojan War. He has tied himself to the ship's mast so that he will not be lured into the waves by the Sirens. But all is not as it seems. Just look at the torment wrought across the hero's face, the eyes glazed with madness. Is it really the Sirens who are driving him from his wits... or is it memories of the war just gone, of things seen and deeds done? In 'The Shadow of Troy' I also:

The Shadow of Troy is my take on the Trojan War. Regardless of how you choose to interpret the legendary story – as a poetic symbol or as a historical record – the outcome of the tale is a sorry one: the Trojans lost everything; King Priam’s line was wiped out and his city was never the same again. Worse, the conquering armies soon discovered that their victory was fleeting, for their realm across the sea quickly fell into the dust of history too. One theory is that they were consumed by a storm of change. But that is another story... |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed