|

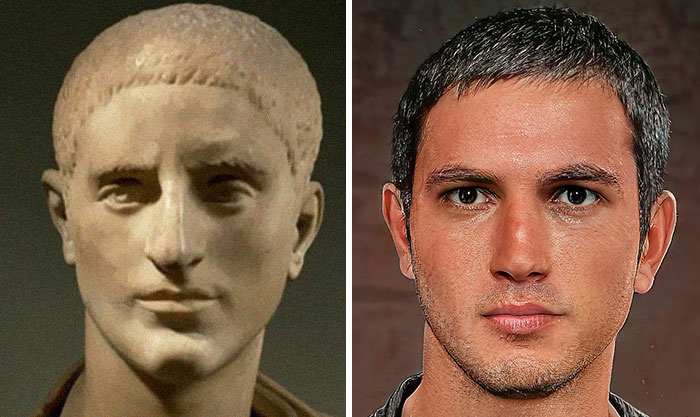

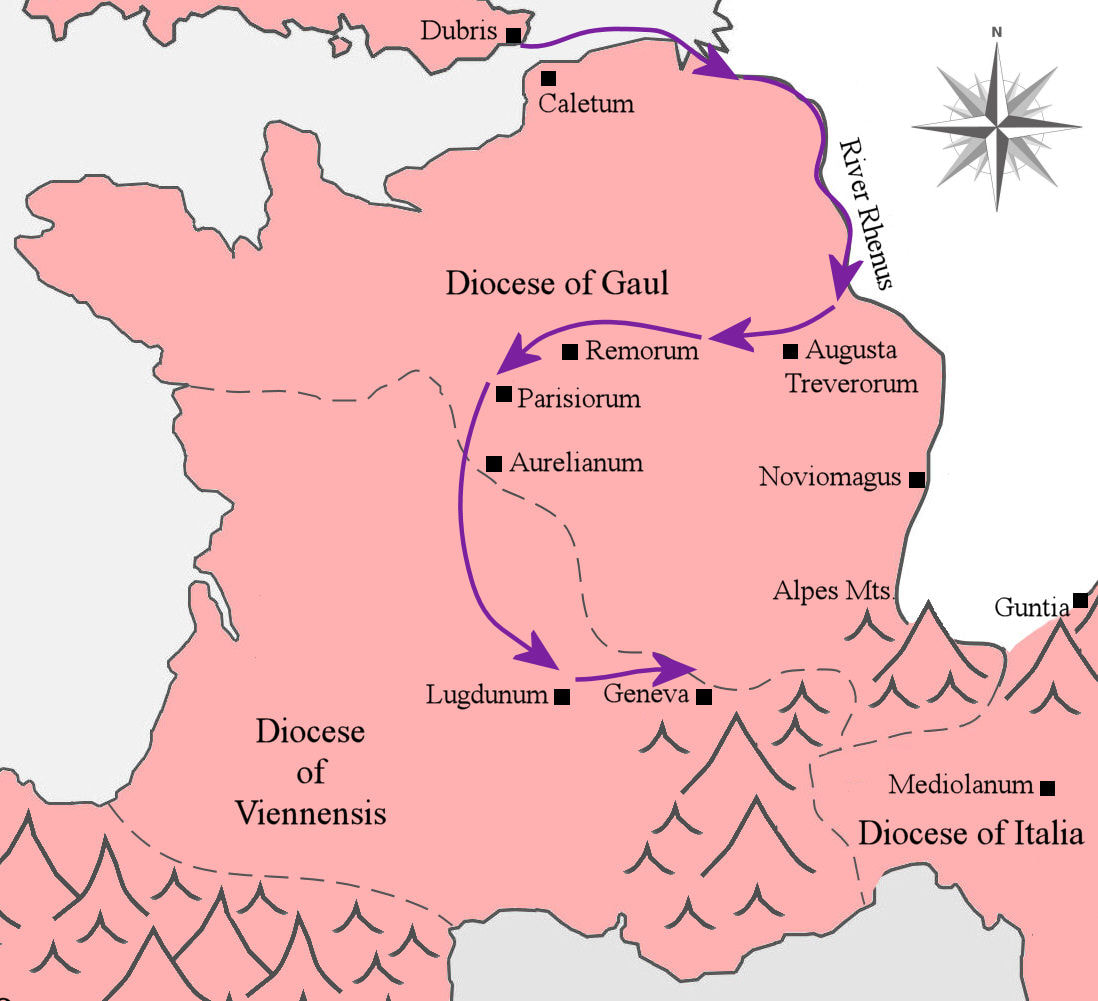

This is Magnus Maximus (meaning "Maximus the Great"). He earned the epithet "Magnus" thanks to a distinguished military career in the Roman legions. Born in AD 335 in Spain, he first rose to prominence in AD 368, when he served as a junior officer in the Heruli - an elite auxilia palatina, or palace regiment of the Western Empire. In this role, he helped the Roman general, Theodosius the Elder, to quell the Great Conspiracy in Britannia - a dangerous movement that saw the garrison of Hadrian's Wall rebel against the empire and ally with several barbarian tribes in an attempt to wrest control of the island from the empire. After playing his part in this famous imperial victory, he would go on to fight and win against the Alemanni on the Danube River and the Moors in Africa. It seems that he might even have played a part in supporting the ascension of Theodosius the Younger (his general's son) to the throne of the Eastern Roman Empire in AD 379. Eventually, he would return to Britannia after being promoted to the position of Comes Britanniarum - master of the island. His next triumph was against the Picts in AD 381. It seemed that his stock was destined to fly as high as the eagles, and that he would be remembered for all time as a Roman hero. Fast-forward seven years, to the 28th August 388 AD. On that day, he was seized by his fellow Romans and dragged out from his new headquarters at the city of Aquileia in northern Italy and, to a chorus of jeering, was beheaded like a common criminal. What on earth happened to bring about this spectacular fall from grace? Envy"Maximus was the countryman, the fellow-soldier, and the rival of Theodosius, whose elevation he had not seen without some emotions of envy and resentment. His provincial rank might justly be considered as a state of exile and obscurity." Maximus was a man of frustrated ambition. He had watched Theodosius the Younger climb all the way to the Eastern throne, and yet he was stuck as the count of the relative backwater of Britannia. Come AD 383, an opportunity would arise to improve his station. On the continent, the reputation of the Western Roman Emperor, Gratian, had begun to slide from favour. His propensity for hunting to the neglect of the empire's problems raised discontent amongst the people. As Gibbon describes: "Large parks were enclosed for the Imperial pleasures, and plentifully stocked with every species of wild beasts, and Gratian neglected the duties and even the dignity of his rank to consume whole days in the vain display of his dexterity and boldness in the chase. Gratian also seems to have let his duty of governance drift into the hands of his bishops and advisors, at a time when the West needed a strong guiding hand. The army too, took umbrage at his favouring of a body of Alani (Iranian steppe warriors) as his household guard. And when he began parading around in Alani warrior garb, they had seen enough. The first standard of revolt was raised in Britannia, where the troops proclaimed their count, Maximus, as the true Western Emperor. Yet Maximus initially refused the acclaim. A modest reaction... or a strategic one designed to absolve him of blame for what might happen next? Regardless of Maximus' apparent modesty, the cries of revolt had been heard across the English channel. Gratian began to mobilise to meet the threat. Now, with the spectre of the hated Gratian readying to attack his islanders, Maximus accepted his troops' acclaim and stepped to the head of the revolt, announcing that they should strike first, before Gratian could fall upon them. The army of Britannia was already potent, with many seasoned veterans in its ranks. Adding to this, the young men of the island flocked to Maximus' banner, eager to carry him to victory. In AD 383, when he set sail for the continent on board an invasion fleet, it would long be remembered as the first permanent and most drastic removal of the large body of troops stationed in Britain. The elite Dalmaturum (Dalmatian) and Sarmaturum (Sarmatian) cavalry schools in particular were irreplacable. "After this, Britain is left deprived of all her soldiery and armed bands, of her cruel governors, and of the flower of her youth, who went with Maximus, but never again returned" Maximus avoided the obvious landing point of Caletum (Calais) and instead sailed up the Rhine, deep into Gratian's Gaulish heartland, before striking overland. On the way many of Gratian's soldiers - instead of resisting the invasion, joined it. Gratian, in residence in Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris), tried to resist Maximus, but his support crumbled. He fled for Lugdunum (Lyon) where his wife was in residence, with only five hundred cavalry for protection. But Maximus had despatched his chief general, Andragathius, to speed ahead of his fleeing rival. Arriving at Lugdunum first, Andragathius reportedly hid in the veiled litter of Gratian's wife and had soldiers carry it out to greet the fleeing emperor. He then sprang out, armed, upon Gratian. A grim chase ensued, resulting in Gratian's ignominious capture and execution at a bridge in the countryside. The Western Empire had been 'liberated' and Maximus was the new emperor. But in the eyes of the Eastern Emperor, Theodosius, his revolt had been illegal, taking place without even seeking permission from him. An insatiable thirst for powerTheodosius initially accepted Maximus as Gratian’s successor and recognised him as Augustus of the West. However, it was only ever a pragmatic and necessary tolerance, given the difficult times in the East (a period riddled with Gothic and Persian troubles). A permanent and growing tension reigned, with Theodosius weathering accusations of weakness for his inaction against the usurper. Yet the alternative – heading straight to war against the new, well-supported Western supremo – could be catastrophic. Instead, he opted to bind Maximus to an oath that he would satisfy himself with the governorship of Gaul, Hispania and Britannia, leaving Italia and Africa to the young Valentinian II - Gratian's younger brother. Maximus took this oath, and quickly arranged to be baptised, a move perhaps taken to increase his standing with the Orthodox majority in Rome’s growing echelons of Christian power (at the pinnacle of which was Emperor Theodosius himself). The usurper seemed to be doing all the right things in order to be accepted. Yet at the same time, he made the rather unique and macabre decision to keep Gratian’s body unburied. And he carried out the notorious and entirely unjustified execution of Bishop Priscillian - citing withcraft and heresy. These two moves suggest a ruthless and dark side to his character. And soon after swearing his oath to Theodosius, he began pressuring Valentinian to leave his court in Mediolanum (Milan) and join him in his Gaulish capital, Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier). “A father and son” relationship, is how he proposed it… but the intent was clear - an attempt to appropriate the younger man's government. When Valentinian persitently refused this underhand grab for power, Maximus set about swelling his already strong Western armies, raising numerous new regiments and inviting Germanic tribes into his ranks too. Young Valentinian recognised the growing threat. So, in late AD 387, he dispatched Dominus the Syrian ambassador to Maximus’ capital. According to the early Byzantine chronicler, Zosimus, Maximus apparently charmed the diplomat out of his wits, convincing him to take a set of 'gift' legions back to Valentinian's court: "Maximus conferred on him so great honours, and so many presents, that Domninus supposed that Valentinian would never again have so good a friend. To such a degree did Maximus succeed in deluding Domninus, that he sent back with the Syrian part of his own army, to the assistance of young Caesar against the Barbarians." Zosimus’ accounts of what followed are vague. He seems to suggest Maximus, with the rest of his army, followed Domninus the diplomat and the 'gift' legions back through the Alpes and tricked or forced his way through the garrisons there, then penetrated deep into Italia, before seizing Africa too. Valentinian and his mother, Justina, fled east by ship, arriving at the port city of Thessalonica to plead for help from Emperor Theodosius. First, Theodosius sent stern demands for Maximus to relinquish his conquests. Next, he mustered the armies of the East, including a portion of the settled Goths recently settled in Roman Thracia. He also arranged for detachments of Hun, Alani and Iberian foederati to assist them. With the army assemled come the summer of AD 388, he then marched to war with the West. War!Nobody truly wanted this. The last comparable civil clash had been Emperor Constantius' suppression of a Gallic usurper Magnentius thirty years prior, an expedition that had exhausted the empire militarily and financially for many years afterwards. But Maximus’ aggression and seemingly insatiable territorial expansion meant war was unavoidable. Maximus established an advance army at Siscia (modern Sisak), a city strongly fortified by the River Savus (Save), with the intent of blocking Theodosius' landward line of advance towards Italy. His general, Andragathius, was stationed with strong forces on the approaches to the Julian Alps, while his brother Marcellinus lay in waiting with a third reserve army in nearby Noricum. Theodosius and the main body of the eastern army set off along the Via Militaris to meet Maximus' land-blockade at Siscia head-on. Meanwhile, Valentinian and Justina led a smaller band of legions by sea, behind Maximus' lines, to Rome. Valentinian first evaded a last-moment naval ambush led by Andragathius, then landed in Sicily, defeating Maximus’ troops there, before going on to claim the ancient capital. There was also a third prong of attack, with a contingent of soldiers sailing from Egypt to liberate the vital, grain-rich Diocese of Africa. Along the way with the main Eastern land force, Theodosius learned that some of the allied Gothic troops he had mustered by the terms of the peace deal of AD 382 had been bribed by Maximus. It is not clear whether they attacked the legions, sabotaged the march or simply deserted. All we know for sure is that he was denied the services of these tribal warriors. Meanwhile, the two main land forces of East and West finally met in a violent battle at Siscia. Theodosius’ cavalry and legions powered across the River Savus’ ford while Maximus’ defenders rained all manner of projectiles at them. The fighting was fierce, spanning two days and the night in between. Seeking reinforcements, and with General Andragathius absent in his failed attempt to intercept Valentinian at sea, Maximus instead called his brother, Marcellinus, and the reserve army to his aid, but he arrived too late. Thus, Siscia fell to the Easterners and Maximus withdrew. As Gibbon says: "After the fatigue of a long march, in the heat of summer, Theodosius and his army spurred their foaming horses into the waters of the Savus, swam the river in the presence of the enemy, and charged the troops who guarded the high ground on the opposite side." Theodosius pursued for several days until East and West clashed again on the plains near the city of Poetovio (modern Ptuj). This time Maximus was reinforced by the army of his brother. Yet it was not enough: "The enemy… fought with the desperation of gladiators. They did not yield an inch, but stood their ground and fell. Finally, Theodosius prevailed." After suffering this second successive reverse, Maximus retreated to the bulwark city of Aquileia, perhaps expecting to withstand a final siege. However, the quick succession of defeats had irreparably damaged the loyalty of his troops. When Theodosius’ advance guard arrived at the city, Maximus was handed over to them and - as described at the start of this piece - was summarily executed. His head was taken on a tour of the provinces. His son, Victor, was slain by Theodosius’ high general, Arbogastes. Dragathius, still hiding out at sea having failed to halt Valentinian, heard of his master's demise and threw himself into the deep. Hero or Tyrant?So it was an ignominious end for the once promising young commander, Maximus the Spaniard. Was he a Roman hero or a megalomaniacal tyrant? Although he saved Britannia from the Great Conspiracy earlier in his career, he certainly left the island in a bit of a predicament, stripping away the majority of its garrison in order to fuel his wars of ambition against Gratian. AD 383, the date he set sail with the British troops, coincides with the end of any evidence of Roman military presence in Wales. However, coins dated later than this have been found along Hadrian's Wall, suggesting that at least a skeleton garrison remained. And he seems to have remained a charismatic and popular figure to the people of Britannia whom he left behind. The Welsh legend of Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (English: The Dream of Emperor Maximus), recounts how Maximus marries a British woman (creating an imperial British bloodline), and gives her father sovereignty over the island (formally transferring authority from Rome back to the Britons themselves). Later lore also identifies him as the founding father of the dynasties of several medieval Welsh kingdoms, including those of Powys and Gwent. This does not fit with the picture of Maximus being tyrannical, or 'abandoning' Britannia. His reputation on the continental side of the channel does not hold up so well, with his broken oath and attack on Valentinian. Did envy and greed get the better of him? And his keeping of Gratian's body unburied and the murder of Bishop Priscillian - are these deeds as grim as they sound... or were they exaggerated by his opponents in the wake of his demise? Whatever the answer, Emperor Theodosius might have thought that by ridding the world of Magnus Maximus, the Roman Empire would know peace once more. But, as with so many ruinous wars, victory left a void of power in the West. And as we know all too well... power hates a vacuum.

3 Comments

Maximus

3/14/2023 08:12:36 am

I think the first image is a portrait of Maximus Caesar and not Magnus Maximus. The style has nothing to do with IV century.

Reply

Gordon Doherty

3/15/2023 03:03:18 am

We've been chatting on Facebook haven't we? :)

Reply

Shelagh McKenna

12/30/2023 04:23:52 pm

I have always suspected that Macsen was slandered. I suspect Justina, mother of Valentinian II, of framing him. She zealously supported the Arian heresy, which he rightfully opposed - the heresy which claims that Jesus was begotten by God. His correspondence with her on the topic had never been the least bit threatening - read it yourself and you will see - but she was a zealot, and probably she was afraid of him since Gratian's death, even though Gratian had betrayed Macsen's uncle, Count Theodosius, whose murder must have been devastating to his right hand man. I can't help noticing that Macsen approached Milan behind the 'gift' legions, alongside Justina's emissary, not in front of them. And after Justina fled Milan with Valentinian II and Galla, she evaded the ships Theodosius sent for her. When he caught her, doubtless demanding an explanation for her evasion, she offered him Galla as a bride, tempting his ambition (since her daughter's children would be his ticket to becoming the legitimate Emperor) along with the claim that Macsen had attacked Milan. I don't know how she explained trying to evade him - perhaps she said she thought it was Macsen coming after her, but I cannot know. And yet the battle was not in Milan, it was in Croatia. Macsen's unpreparedness for battle, calling for his brother and son, suggest that he was not expecting a conflict. And I think it is significant that Theodosius hated Justina after this. It is generally admitted that he had her killed. He turned mean, and Valentinian II lived the life of a captive. The game did not work well for her.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed