|

When we set off down to Hadrian's Wall country the other week it was for a number of reasons:

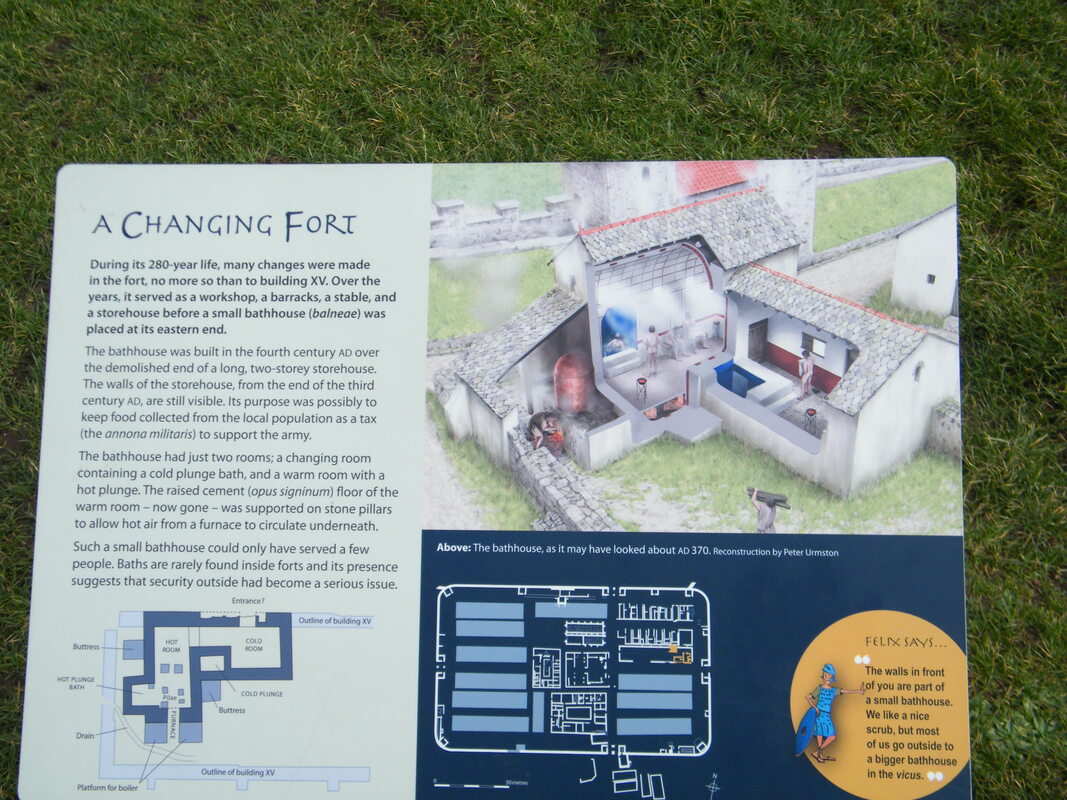

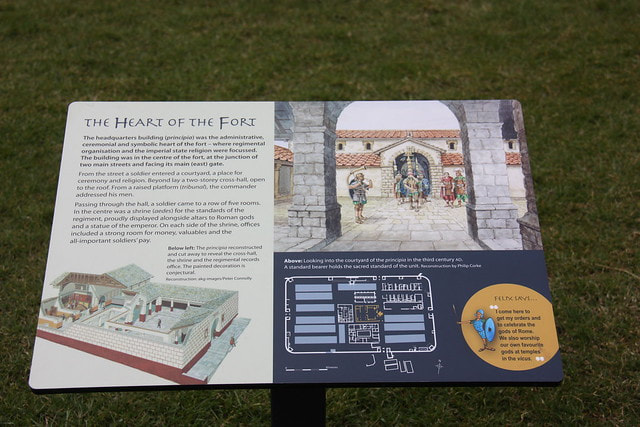

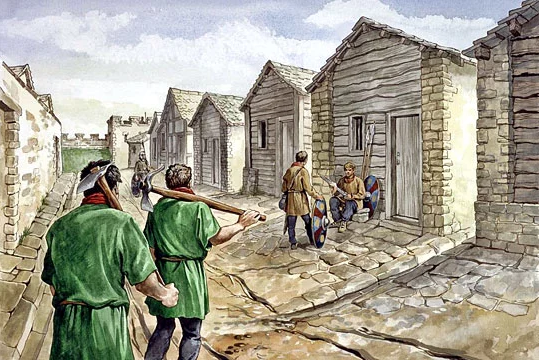

We hired a Volkswagen T5 camper van - tall enough for me to stand up in, and small enough to be an easy-ish drive. Ironically, it was the petite Sarah who found the ceiling height an issue - constantly thumping her head on the lower bits because she's not used to having to duck under things like me. Of course, I was very supportive when this happened... :) Anyway, off we went for a weekend of exploration. The focal point of our visit south was Housesteads fort - or Vercovicium as the Romans would probably have called it. It had been years since I had last come here, and I had heard of many changes since my last visit. When the fort rolled into view, I could not contain a Beavis and Butthead style 'coool!'. Perched atop Whin Sill ridge, the fort commands an excellent position from which to observe the surrounding lands - in particular, the Knag Burn, which runs through a gap in the ridge and presents a weak spot in the terrain. This fort was the home of a vexillation of the Legio II Augusta in the 2nd century AD and, when they moved out, a cohort of Tungrian auxiliaries (made famous in Anthony Riches' Empire novels) moved in to serve as the permanent wall-garrison. Although just a few feet of foundations have been exposed by the excavations, Vercovicium's walls are thought to have stood at three or four metres high in their pomp. We parked up and hopped out of our van only for a bitter, wintry squall to do its best to blow us back inside, mocking our initial choices of 'just a fleece'. So, five minutes later (this time kitted out with hats, scarves, gloves and three jackets each) we hiked up the hillside, coming first to the remains of the vicus. This cluster of structures outside the fort's southern gate once formed an informal sprawling 'town centre' for the off-duty soldiers to empty their purses. The fort museum had a really nice artist's impression of what the vicus might have looked like in its heyday, and it really does paint a rather intimidating picture with shops, taverns and brothels craning over the main road that led up to the southern gate, almost dwarfing the fort walls. But the fort gatehouses were designed to trump anything else on the landscape of northern Britannia, and the southern gate would certainly have stood proud of these less salubrious structures outside. Inside the fort and atop the ridge, the gale roared ferociously and cut through my three 'wind-proof' jackets like a spatha through a Goth's belly (check me and my simile magic). I can only imagine how the non-native legionaries and auxiliaries posted here from more clement lands might have coped with it. It is likely that the landscape was far more thickly forested in the era of Roman occupation, so it may not have been quite as exposed, but I'd imagine that thick woolen cloaks, tunics, trousers, socks and closed boots would surely have been their garb of choice for the winter season. Blue-faced, we set off on a tour around the fort. At this point, I felt a sense of calm overcome me. There is something reassuring about coming to each section of a Roman fort and knowing beyond all doubt what will be there, what will lie behind, beside and before it and why. I imagine the troops would have felt a similar sense of security at this. We trekked across the parallel rows of barrack blocks on the fort's western wing. These long, narrow buildings took up the majority of the space inside the fort's eastern and western sides. They would have housed a century of men each, squeezing contubernia of eight into painfully cramped rooms where they would sleep, dress, eat, play dice, and no doubt goad each other mercilessly about the toothless hags from the vicus they had gone with the night before. Next, we skirted by the fort's western walls. Here, a neat illustration along the inside of the walls shows how an earth embankment once reinforced the stonework, and how the garrison took to embedding oven houses in these embankments to bake their daily bread. The ovens were probably placed here, as far away from the structures of the fort interior, to reduce the chance of fire. We then cut into the heart of the fort. Here, the uniformity of the barrack blocks is replaced by the rather more grand command centre. The principia is the beating heart of any Roman fort, and here it is no different. A small, colonnaded courtyard backs onto a tall cross hall, inside which the commander would address his officers, and the unit standard bearer (signifer or aquilifer) would hand out pay to the rank and file. This structure also housed the precious garrison standards. Standing here at the centre of the fort, we could see just how severely the hillside fell steeply away to the south-east, leaving the corner of the fort there several metres below what was ground level for the rest of the fort. Rather than whingeing about this slope, it seems that the garrison put it to good use, building stone-lined water tanks into this sloping hillside to collect running rainwater (water was otherwise sourced from the nearby Knag Burn). They had also stuck to the usual system of building the latrines on the south-east corner of the walls, at the very lowest point of the fort (fortunately lower than the water collecting tanks - otherwise I'm not sure I'd be up for a cup of water-tank brew). Hemming the principia are three other key buildings. The valetudinarium - a rectangular building framing a small courtyard immediately west of the principia - served as a hospital, where the ill and wounded would be treated by the medicus ordinarius (equivalent to a doctor), his capsarii (nurses/wound dressers) and his medicii milites (orderlies). South of the principia lies the praetorium - the fort commander's house. This lavish, multi-floored Mediterranean-style villa was built in stone at first, then finished with timber. It is thought to have served well in sheltering the residents from the harsh winds and rain. Even with just the foundations on view, it is clear just how starkly it must have contrasted with the cramped, draughty barrack blocks. North of the principia, the foundations of the horreum (granary) are on show. The stone pillars served to raise the floor from ground level and prevent the grain inside from spoiling due to damp or vermin. It is thought that small, square holes in the granary walls served to allow air to circulate and help keep the grain dry - and to let dogs leap in to chase or catch brave rats (though who's to say the dogs didn't help themselves to a few mouthfuls of grain whilst they were in there? Seriously, dogs'll eat just about anything - mine once ate a kilo of butter in one gulp!) Just north of the horreum, the foundations of a very interesting structure have been excavated: turret 36b, as it is rather prosaically known, is thought to have been one of the original turrets on the wall, before Vercovicium was commissioned. On to the fort's north wall, standing flush with Hadrian's Wall itself. The view is rather spectacular here. The north wall and gate almost overhang the edge of the Whin Sill ridge. Practically, however, the north gate must have been something of a pain in the posterior to soldiers and traders, with a sharp climb or descent to enter or leave the fort. Over time, the north gate fell out of use, and the Knag Burn Gap - just to the east of the fort - became the main thoroughfare for north-south movement. And it was the changing shape of the fort that really snagged my attention. I've made it quite clear that the later empire fascinates me more than any other period, and it seems that a few things have come to light in this respect since my last visit (or perhaps they escaped my attention before). After the classic legions had faded into history, leaving the limitanei to serve on the empire's borders in the 4th century AD, Vercovicium changed significantly. The long, narrow barrack blocks are thought to have been demolished and replaced with 'chalet' style huts. It may sound more luxurious, but the likelihood is it was less expensive to build and maintain such structures. More, one opening on each of the fort's four double-gates seem to have been bricked up. Perhaps because the flow of people to and fro had lessened, or maybe because it made the gates more easily defensible? Adding weight to this second theory is the fact that the vicus outside the southern gates appears to have declined and then fallen out of use entirely, and a balnaea (a very small thermae/bathhouse) was built inside the fort over a demolished stable. Bathhouses like this were typically built outside Roman forts (usually in the vicus or near rivers/burns), so this adds weight to the theory that it might have been dangerous ground outside Vercovicium's walls in the Western Empire's later years. Indeed, the rest of the empire was contracting rapidly as the 5th century approached, with outlying legions and auxiliary cohorts being recalled to defend against the barbarian incursions across the Rhine and Danube, so the changes to Vercovicium do indeed seem to be an indication of these darkening days... Chilled to the bone, but fully charged up with ideas about the last days of the soldiers on the wall, we popped back to the camper van for a steaming hot cuppa, ready to return home. But before heading back north, we made a point of stopping at the Mithraeum at Carrawburgh (Brocolita) Fort. The weather was getting silly at this point (the pic below was cribbed from Google as my camera lens was just a blur of rainwater), with my boots sinking a foot or more into mud/swamp, but I soldiered on to come to the sunken temple. I stood before the altar, then knelt down on one knee. I was pretending to shelter from the wind and rain, but secretly, I was actually acting out a scene I have in store for Tribunus Gallus in the next volume of the Legionary series. Of course, that doesn't mean I'm going to portray him touring the wall in a camper van . . .

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

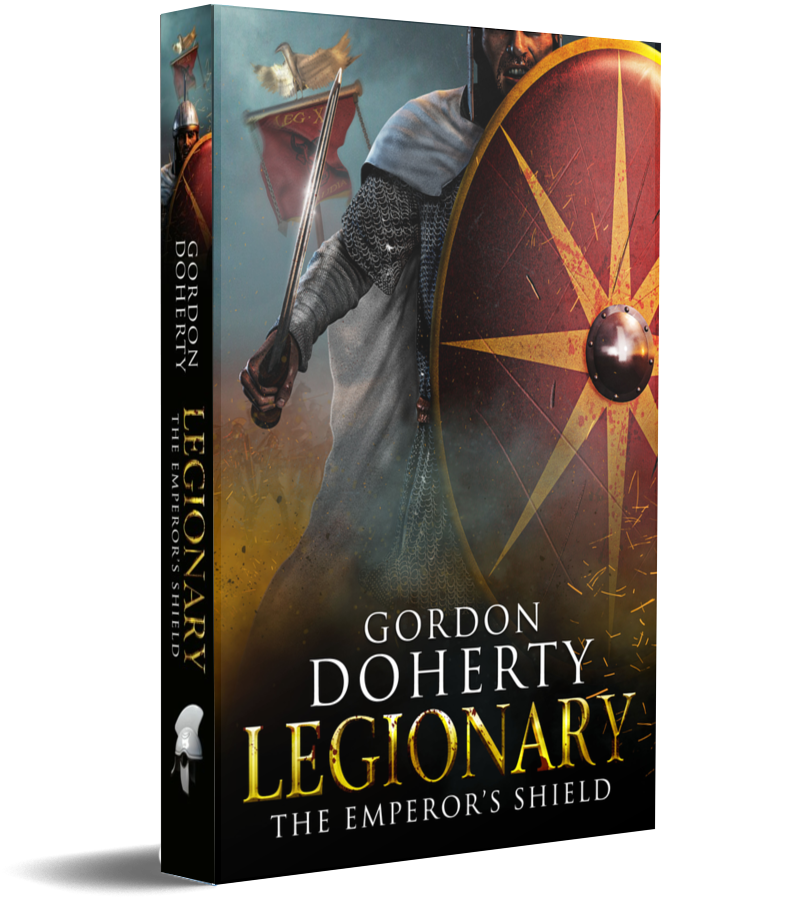

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed