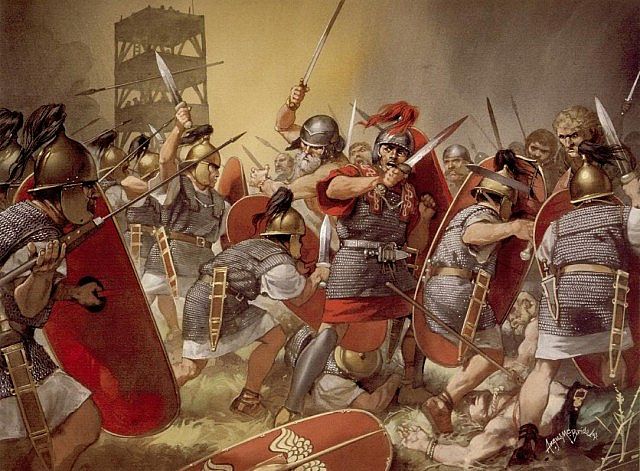

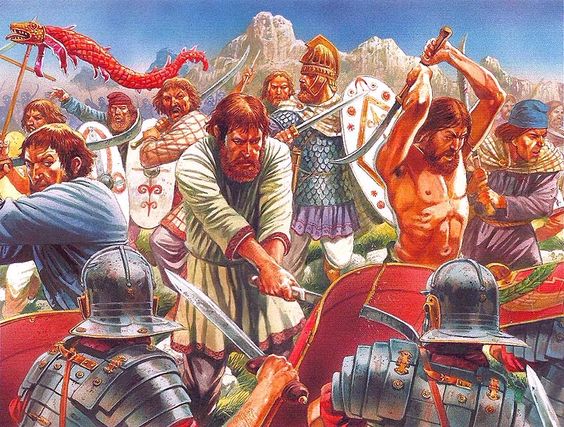

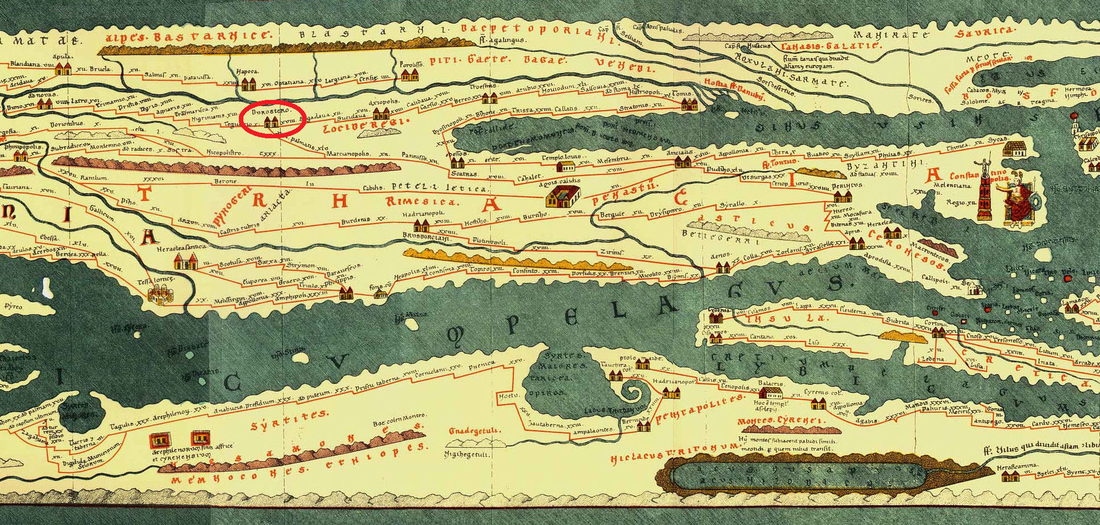

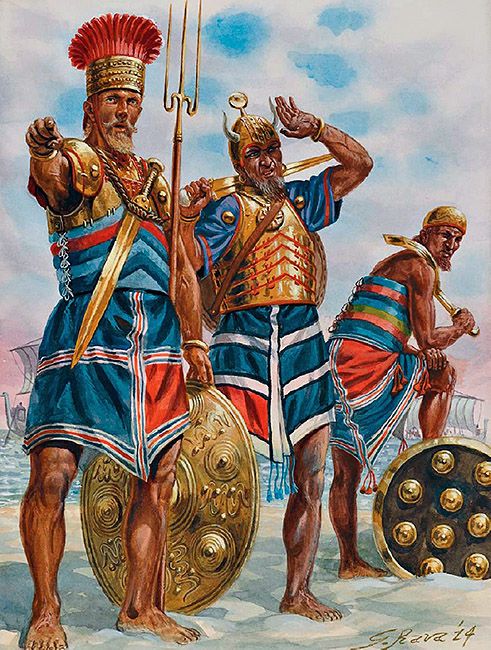

OriginsIt all began back in 58 BC, when Rome was still a republic. A little-known fellow by the name of Julius Caesar started things. In need of fresh manpower for his impending invasion of Gaul*, he raised several new legions. One of which was granted the name 'the Eleventh Legion'. The Gallic WarsThe Eleventh legion fought throughout Caesar’s Gallic campaign, notably against the Helvetii at the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BC, then against the Nervii confederation in 57 BC and in the famous Siege of Alesia in 52 BC. And after Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon and claiming of the city of Rome, the Eleventh Legion went with their general in pursuit of his great rival, Pompey the Great. The Battle of Dyrrhachium and the Battle of Pharsalus were fought in quick succession during the hot and bloody summer of 48 BC, with the Eleventh Legion and Caesar emerging as clear victors. In 45 BC, after thirteen years of hard campaigning and with the Roman world now stable and all neat and tidy again (mwahaha – if only they had known!), the Eleventh Legion was disbanded, its soldiers granted the old Samnite lands of Bovianum in southern Italy, to farm and live out their lives in peace… ...aaaand then Caesar was assassinated. The Roman world was thrown into chaos all over again. Fighting to avenge his slain great-uncle, Octavian recalled the Eleventh Legion from their pastoral retirement. They fought against the assassins and revolutionaries in Greece, in Sicily and through Italy and finally, they faced and defeated Mark Anthony in the naval clash at Actium which finally ended this latest bout of civil war. But there was to be no return to the peaceful farmlands of Bovianum – for the now well-scarred veterans of the Eleventh were instead sent to garrison Dalmatia (modern Croatia). Empire RisingFor a time, several generations in fact, the Eleventh Legion knew relative peace. Legionary fathers would have watched on as their sons enlisted in the Eleventh ranks, while back in Rome, the reign of Octavian (now Augustus) saw the Roman Republic fade out and the new system of empire rise in its place. Octavian was shrewd enough to go for a soft approach to this, never referring to himself as an emperor, only ever as a ‘Princeps’ (meaning ‘most senior of senators’ but to you and me: ‘the boss’). This era of Roman government, known as the Principate, would last for nearly three hundred years. Fast-forward to 42 AD, when Claudius ruled the empire. A chap named Scribonianus, presumably bored with the relative stability of the time, decided to revolt against Claudius, and chose to begin his tantrum in Dalmatia. The Eleventh Legion were one of the first to react in support of the emperor and against Scribonianus. So, when the rebellion was put down, the emperor bestowed upon the Eleventh the honorific title ‘Claudia Pia Fidelis’ (Faithful to Claudius). And so, the XI Claudia proper was born! A less-than-glorious episode followed in 69 AD – the so-called Year of the Four Emperors – when the XI Claudia sided with one of the four brief imperial claimants, Otho. They arrived at the Battle of Cremona to support him against his rival, Vitellius, late. By then, Otho had been defeated, but fortunately, Vitellius did not punish the XI Claudia, simply sending them back to Dalmatia, chastised. But that didn’t stop them from siding with a certain Vespasian when he came along to challenge Vitellius, and this time the Claudia arrived on time and helped win the Second Battle of Bedriacum to install Vespasian on the imperial throne and end the domino-like succession pattern of that year. In the following years, the XI Claudia were stationed on the Rhine, holding that frontier and at times participating in campaigns into the boggy woodlands beyond – notably under Emperor Domitian against the Chatti in 83 AD. Over the next half-century or so, the Claudia drifted eastwards, finding a temporary station in Pannonia (roughly present-day Serbia) before following Emperor Trajan east as a vital part of his conquest of Dacia, then finally arriving at the place that would be their home for centuries to come: Durostorum (modern Silistra, Bulgaria) on the River Danubius. The Coming of the DominateWhile stationed at Durostorum, the Claudia were responsible for manning the lower Danube and its delta with the Pontus Euxinus (the Black Sea), as well as protecting the Roman-Greek colonies of Bosporus (modern Crimea). They and sister legions the I Italica and V Macedonica became a de-facto border garrison of those parts. And this new, more permanent role was perhaps symptomatic of the change in imperial governance and military strategy that came about in the late 3rd century AD. Bit of a tangent here, but you’ll see why it is relevant to the XI Claudia (bear with me)… Beginning with Emperor Diocletian in 284 AD, the nature of empire changed. Emperors no longer pussy-footed with titles such as Princeps (honest guv’nor, we’re all equal), instead declaring themselves as out-and-out emperors (listen, pleb, I'm amazing and you're not). Gone too were modest ceremonial effects like the wearing of the ancient purple toga, Diocletian and his successors instead choosing to paint their skin gold, call themselves the embodiments of gods (referring to themselves as 'Sired by Mars' and the like, apparently), wear jewel-encrusted cloaks, opulent crowns and purple slippers – more akin to Persian Shahs than Roman leaders. More, subjects were required to prostrate themselves before the emperor, crawl towards him and kiss his slippers (hoping he’d washed his feet) and address him as ‘Domine’ (lord or master). This autocratic era of empire came to be known as the ‘Dominate’ thanks to its stark contrast to the earlier Principate. You could be forgiven for thinking this was a big ego-trip for Diocletian – who probably sounds like the Cristiano Ronaldo of the Roman Empire – but like the Portuguese preener, there was substance behind Diocletian’s style. For the half-century prior to his rule, the empire had endured what is now referred to as ‘The Third Century Crisis’ – a storm of civil wars, economic collapse and pestilence. Twenty-six emperors came and went in those fifty years and the empire was in danger of crumbling away altogether. As such, a firm hand was perhaps the appropriate way to reassert control over the ailing state. Diocletian experimented with the Tetrarchic system, splitting the empire into four parts each with a clear ruler and successor. An understandable move, given the prior problems. But he got a lot of things wrong too: tinkering with the waning economy by introducing unworkable maximum-pricing edicts and ‘un-pegged’ golden coins; trying to ‘fix’ the religious strife of the time by triggering the Great Persecution of the Christians... both disastrous choices. Militarily, it is questionable whether he got things right or wrong. The legions of old, XI Claudia included, had proud histories. Five-thousand strong armies that could oversee a stretch of imperial border, or march beyond to invade, or turn inwards to an interior troublespot in times of need. But times had changed and, as the Third Century Crisis had shown, the army of the Principate was incapable of simultaneously manning the imperial borders and keeping Roman usurpers or barbarian invaders who made it into the empire in check. Thus, Diocletian started the process of breaking down the old legions into broad ‘classes’. Instead of monolithic five-thousand-strong legions on the borders, he began to form ‘field’ armies, stationed in the heart of each of the major regions of the empire. These armies, composed of new, thousand-strong ‘comitatenses’ legions, were supposed to be the crack forces who could deal with internal strife or deal with any invaders who made it through the imperial borders. And on the borders, adding the outer layer of this new ‘defence-in-depth’ strategy, were the ‘limitanei’ legions (the ‘limes’ being the edges of the Roman Empire). It was the job of the limitanei to repel, or at least slow and track invaders until the local field army could be hastened to the trouble spot to crush them. And that is where the XI Claudia ended up – as limitanei, watchmen of the lower Danubius. Now a lot has been said about the contrast in status and capabilities between the comitatenses and the limitanei (ranging from ‘they weren’t too different’ to ‘the limitanei were rubbish!’), and I touch on those differences here, but the fact is the limitanei were vital: without them, the empire’s edges would have been completely porous and undefined. More, it seems that the limitanei and the Claudia in particular were highly valued beyond their border watch status – over the years, vexillations of the Claudia were sent from their base at Durostorum to places such as Judea, Persia, Egypt and Mauretania, so they were clearly not just some makeshift peasant militia. Hope you enjoyed the read! Now, if you'd like to read about the adventures of those late empire Claudians...

Key References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGordon Doherty: writer, history fan, explorer. My Latest BookArchives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed